‘Blackity’ sheds light on the disparities of representation in Black Canadian art

Dr. Joana Joachim gathered information from as far back in time as she could to curate ‘Blackity’. Courtesy Paul Litherland

The exhibit stands as a testament to the neglected preservation of Black art history in Canada

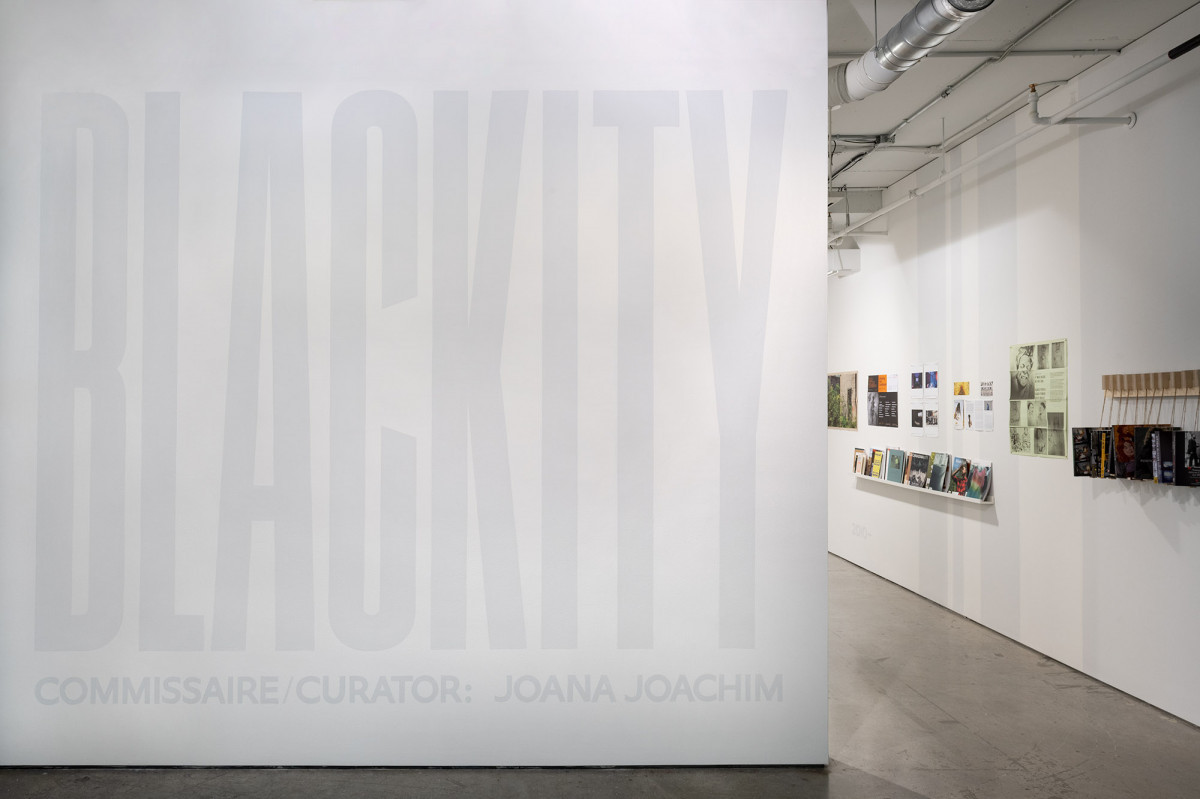

The exhibition space for contemporary art known as Artexte is hosting its latest feature installment–Blackity: a memorabilia of contemporary Black Canadian art ranging from the 1970s until today.

Curated by Dr. Joana Joachim and set in the heart of Montreal, it sheds light on the disparities found in the preservation of Canadian art among non-white racial communities. Through a variety of books, catalogs, journals, and short films, viewers can witness the neglect of Black art firsthand, and its impacts on Black historical timelines in Canada.

Joachim came across Artexte after working alongside the Ethnocultural Art Histories Research Group at Concordia in 2015 whilst completing a research residency on the presence of Black and Asian influences in Canadian art. During her residency, and after having worked closely with Artexte’s team over the years, Joachim’s research sparked the inspiration for what would later become the conglomeration of works that constitute Blackity today.

“One of the primary things that I was looking at was [how] the Artexte collection allows me as a curator to learn about what was happening all those years ago, and what is happening now,” Joachim said.

Artexte’s permanent collection contains various archived forms of contemporary art and documents ranging from 1965 up until today. A large portion of Artexte’s catalog is freely accessible through e-Artexte, the gallery’s online archival database. In terms of Black Canadian art, Joachim was only able to uncover documentation of artists’ work from the 1970s onward.

This is not to say that there is no documentation of Black art prior to the ‘70s. The truth is that the process most art historians exploring Black diasporic histories in Canadian art go through requires extensive research. Sometimes, it involves having to categorize a sort of temporal cartography that attempts to mimic a timeline–as Joachim has done with the installment of Blackity–to trace the roots of Black art in Canada. In Joachim’s case, and given the gallery’s facilities, she felt propelled to gather information from as far back in time as she could.

“I think that there are definitely trends in time during which we’ll notice that there is more documentation or less documentation, and that’s one of the things I explore in the exhibit,” she said. “I think it’s kind of a reflection of what was happening socially in Canada, and also a reflection of who was working where.”

Altogether, Joachim’s research in Blackity begs a number of questions about the way our institutions have preserved or negated the value and significance of the work done by Black Canadian artists. Some of the inquiries examined by the curator in this particular project include who the people responsible for curating Black art were, which institutions were involved in its processes, and whether the people involved in those institutions were paying attention to what Black, Indigenous, and People of Colour were doing in terms of art.

In consideration of the overall lack of exposure that Black art has faced in Canada, Artexte prioritized Blackity’s accessibility among audiences both online and in person. According to Anabelle Chassé, the gallery’s communications assistant, the online exhibit expands beyond Artexte’s collection by including references and links to additional institutional websites. By providing these resources, viewers can have a better encompassment of the featured artists’ efforts altogether.

“I think it’s kind of a reflection of what was happening socially in Canada, and also a reflection of who was working where.” — Joana Joachim

The in-person visits not only offer a more tangible experience, where people can actually touch and read the documents displayed. Visitors also have access to two short films that are not available in the online exhibit.

The phenomenon on Black art’s cyclical disappearance and reemergence throughout history has significantly impacted not only our collective understanding of the plethora of narratives told within its frameworks. It has also contributed to the erasure of Black artists’ voices as a whole, which is what Blackity demonstrates.

One of the takeaways visitors will remember after touring Blackity is the overwhelming realization that Black artists were forcibly confined from gaining public exposure–several of whom are featured among Joachim’s selections–in a way white artists were not. This was seen in the early 1970s leading into the 1980s, when Canadian art was trademarked by the collective works of white men. Joachim confirmed that the exclusion non-white artists were facing at this time inspired many to explore themes of identity and racism in their work, thus sparking conversations about the same societal exclusions within Canada’s artistic community. Ergo, their art forms became tools for public discourse.

Still, there were a handful of Black male artists whose work became publicized, often under the guise of tokenism. The same artists would reappear in publicities as opposed to new competitors in the same racial demographic, who were otherwise ignored or forgotten. As such, this discriminatory process lessened the pool of representation among BIPOC artists in Canada.

Joachim’s selections depict how some artists, who were active for decades, only gained exposure some 30 or so years after their initial start. Such was the case with most Black female artists, who only became visible in the overarching arts community in the mid-1980s.

One catalog in the exhibition called La constitution d’une Nation features artwork by artist Khadejha McCall that reflects this polarization in depth. It cites that although some of her work was finally published in 1993, she had been actively making art in Canada and the United States since 1967. However, there are no traces of her work prior to 1993, leaving a gap in the artist’s legacy.

“It’s both an unfortunate and damaging reality of the history of Canadian art and Black art, especially for independent researchers who are forced to base their work on what is essentially an incomplete history,” Chassé added. “There is a basis of responsibility that is expected from institutions to correct and conserve the historic traces of these practices, which has not been fully met.”

Read more: ‘Constitutions’ exhibition critiques caste politics, capitalism, fake news, and oppression

Read more: Sounds and sights from the everyday on display at Fonderie Darling

The work Artexte’s librarians do plays an important role in the overall preservation of art by emerging and longtime running Canadian artists, whose work became lost and forgotten relics over time.

“Almost every document that we acquire is through donations from the community, so from artists and arts organizations–almost 80 per cent [of them],” said Hélène Brousseau, one of Artexte’s librarians.

“There is a basis of responsibility that is expected from institutions to correct and conserve the historic traces of these practices, which has not been fully met.” — Anabelle Chassé

In the physical space at Artexte, the time frames Blackity represents are categorized by stripes of varying widths. Each stripe’s width represents a period of time from between the ‘70s until today where Black art was most or least prevalent. In this way, the space attempts to classify the fragmented history of Black Canadian art.

According to Mojeanne Behzadi, Artexte’s curator in charge of research and programming, visitors are encouraged to get intimate with Joachim’s research and her knowledge of the collection at Artexte through Blackity. The culmination of her research is a testament to her influence in the collection’s files and dossiers, and will remain on display until March 26, 2022.

Behzadi thinks people should look beyond the stories told through showings at bigger art institutions, and pay closer attention to what is going on in small artist-run spaces and community centres instead.

“I think young writers and emerging art critics should really pay attention to what’s happening in smaller spaces and write about those exhibitions because that’s the first step in making sure that artists’ traces remain,” she added. “We all have a responsibility in keeping the work alive, and making sure artists’ legacies continue well into the future.”