A Broken Homestay

Concordia International Student Condemns Montreal Housing Conditions

Xiao-Ming was never sure whether to leave the light on or off.

If he switched on the light in the empty kitchen, his landlord would scold him, asking him why he was wasting electricity. If he shut it off, he would hear more complaints about his apparent lack of judgment.

Xiao-Ming—a pseudonym—says this was part of a problematic two-month homestay situation last semester. He moved to Montreal from Beijing to pursue graduate studies in computer software programming at Concordia University.

The international student will be filing a violation this week to Quebec’s Human Rights Commission for discrimination based on ethnic origin and language, with the help of the Centre for Research-Action on Race Relations.

“We want to see if we can hopefully create a precedent for international students in homestay situations,” said Fo Niemi, CRARR’s executive director.

Deciding whether to leave the light on or off was only one of Xiao-Ming’s worries. From Sept. 6 to Nov. 1, he lived in a duplex located at 1215 Gohier St., only a few blocks away from the Cote-Vertu metro in Ville Saint-Laurent.

Xiao-Ming had an eight-month lease with his landlord, Ju Ming Eh, who signed his name on the document as “Jupiter.” The duplex has three bedrooms on two floors. Ming Eh lives there with his wife, Grace Hsieh, and their children. They moved to Canada from Taiwan almost two years ago.

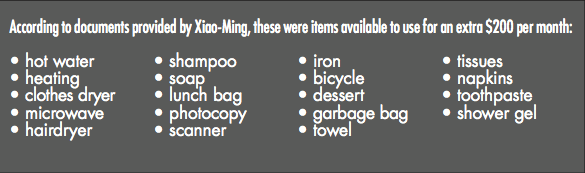

The homestay lease stipulated that Xiao-Ming would be fed three meals per day and “others as attached.” No utilities were included within his $850 monthly rent. To use basic necessities such as heating or hot water, he would have to pay an additional $20 per month.

When the temperature started dropping in October, Xiao-Ming says his landlord never responded positively to requests to raise the heat.

“‘In my home, winter begins in December,’” Xiao-Ming remembers his landlord saying.

To gain access to a list of basic items like a clothes dryer, printer, microwave, toothpaste, or even dessert, the landlord set an additional monthly cost of up to $200. Xiao-Ming says he never paid more than the $20 fee associated with heating and hot water. He didn’t see the list of extra costs until after the lease was signed.

The food, Xiao-Ming says, also made his stomach sick. His meals every day consisted mainly of carrots, potatoes and rice, with the occasional meat portion. The student from Beijing says the students living there often ate leftovers.

Like the concerns about heat, the complaints over the food were ignored, Xiao-Ming says. So, on Nov. 1, he left.

On Dec. 8, he received a legal notice from his former landlords, who demanded two months worth of rent.

Hsieh and Ming Eh offer three rooms for students. According to the Régie du Logement, homestays with up to two bedrooms are considered personal situations and do not require a lease. With three rooms or more, tenants and landlords are required to sign a lease. Upon arriving in September, Xiao-Ming was given a month to decide whether to stay or find a new place to live. At the beginning of October, he signed a lease, which was supposed to end in July. Hsieh says Xiao-Ming broke his lease in November without notice, and the room was left empty for two months.

Xiao-Ming says the landlord threatened to use his passport and study permit against him to ensure that he wouldn’t find another place to live. He says he has “no idea” how they got his documents, but Hsieh says she asked for them before making a copy.

According to the Commission d’accès à l’information, landlords can ask to see official documents, but do not have the right to collect the information or photocopy them.

At least four students, including Xiao-Ming, have left the homestay since last October.

The international student found the duplex in Montreal through Bright International Student Services Inc., an agency based in B.C. He signed a contract in China with BISSI, who he found through a Chinese organization. The firm, New Oriental Education and Technology Group, provides international study consultation and private education services.

Xiao-Ming says he paid New Oriental $5,000 for beginner English lessons and to help with his application to Concordia, as well as paying BISSI $1,830 to help him locate a homestay.

“Students will choose to stay with a family, because they think that means they’re going to be taken care of well.” —Leanne Ashworth, Concordia Student Union Housing and Job Bank

BISSI kept $830 in fees, for services like airport pick up, plane ticket booking, help setting up medical insurance, filing tax-returns, opening a bank account as well as a cell phone plan and purchasing public transit tickets.

Only half of the services were provided, Xiao-Ming says. The rest of the money went towards a rent deposit. When he arrived in Montreal he received $575 back of the $1,000 deposit. The rest of that money went towards first month’s rent.

Two media representatives from New Oriental were contacted, but could not be reached by press time. A member from BISSI said they find homestays through online ads, which is how they found the one in Ville Saint-Laurent.

BISSI then send a worker based in Montreal to inspect the house, interview the host family, and check for criminal records before connecting students there. If the student has a satisfactory experience, then they continue to use the homestay, the worker explained over the phone. He said English documents detailing the different packages they offer were confidential, as he declined to give his name before hanging up.

Xiao-Ming had the choice between an English or Chinese homestay. He was originally supposed to stay in an English home because he wanted to improve his language skills. Despite the original agreement, he received a call from BISSI three days before he was expected to arrive in Montreal offering him a spot in a Chinese homestay instead.

“I had no time,” he says. “I had to say yes.”

Recruiting internationally

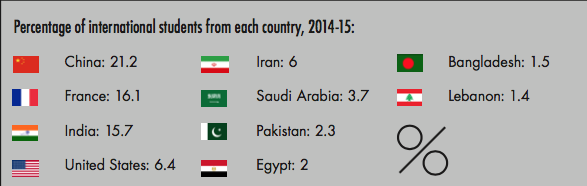

Concordia sends a team of three to four people approximately eight times a year to speak with students in China, according to Matthew Stiegemeyer, the university’s director of student recruitment.

“We try to be ready to assist students with any questions they have with interest or vague [awareness] of Canada,” Stiegemeyer explained.

Stiegemeyer and his three-person team visit major cities such as Beijing and Shanghai. Some team members are native Mandarin speakers. They arrange to speak at schools, convention halls and even directly with students over coffee, Stiegemeyer said.

In 2012, The Link broke a similar story regarding a controversial homestay situation for international Chinese students. The main difference was that an external agent with a Concordia email address arranged the homestay.

To his knowledge, the university hasn’t hired a third-party contractor to act as an intermediate in recruiting processes since 2012, but Stiegemeyer wouldn’t rule out “one-off” situations. As for students hiring their own agent or a third-party company—like New Oriental or BISSI—he says they don’t explicitly tell them not to, but if asked, they discourage their usage.

Stiegemeyer says they are most interested in the academic programs offered and what it takes to be accepted. One of the requirements is taking an English fluency test.

Depending on their test scores, a student may have to take at least one ten-week session of English lessons at the university’s language institute, which costs $3,995.

Although Xiao-Ming has been accepted into a graduate studies program for computer software programming, he has yet to take a course in the subject. He first has to complete three levels of English studies, which he expects to finish in June at a total cost of about $12,000.

2_685_1050_90.jpg)

How Concordia can help

After being accepted into Concordia, international students receive an admissions package that includes a pre-departure guide, outlining what they should do before coming to Montreal. Page 13 of the guide states, “Do not sign a lease for an apartment or commit to any long-term off-campus housing arrangements until you arrive in Montreal.”

Students can have an agreement with a landlord before they arrive, but shouldn’t sign a lease before they’ve seen the living arrangements.

The university recommends admitted international students book a hotel room for the first few days in the city, according to Kelly Collins, manager of Concordia’s International Students Office. Xiao-Ming signed a contract with BISSI in China, but he signed the lease with the homestay landlord in Montreal.

“Students will choose to stay with a family, because they think that means they’re going to be taken care of well,” says Leanne Ashworth of the Concordia Student Union Housing and Job Bank. “They’re willing to pay extra for that because they think they’re going to be safe. I think it’s especially disappointing that that kind of trust is abused.”

The ISO runs webinars from March to April, Collins explains, where students can watch an online presentation and have questions answered live by a representative. In-person orientations are also offered when most students arrive in July and August, she says. The ISO provides information about tenants’ rights, using pamphlets and documents from HOJO.

The CSU-run organization offers its information in Mandarin.

One of Xiao-Ming’s English teachers referred him to HOJO after learning of the homestay situation. HOJO then referred the student to the Concordia Student Union Legal Information Clinic.

“Concordia is getting so much money, surely they can allocate more of that money to try and resolve [the housing] problem,” says Walter Tom from the clinic. “We’re two [CSU] services with a limited budget.”

Finding a home in a new city

Foreign students can feel restricted from speaking out about housing conditions, because they’re afraid of losing their international student status and being kicked out of the country, says Ashworth.

“It’s very easy for the institution to say, ‘It’s not our problem.’ But wait a minute, you’re bringing them here to study at Concordia, it is your problem,” Tom says. Housing conditions can have a lot to do with students’ success, he continued.

Xiao-Ming left Beijing to pursue graduate studies in Montreal because he wants to work for the video game company, Ubisoft.

So far, the international student says Montreal has been peaceful and quiet. He doesn’t yet consider himself a real Concordia student to give an opinion on the university, but he expects to start his computer software programming degree in September.

In early March, Xiao-Ming moved into a new apartment. He’s been living with a friend since he left the homestay. Xiao-Ming found his new apartment online, and now only pays $460 per month.

Does this story sound familiar?

In 2012, The Link published an exposé on a problematic homestay situation in Montreal, which also involved students from China. There were many similarities to Xiao-Ming’s situation: the use of the agency New Oriental, high monthly rent, poor quality of food, and the need to enroll in Concordia English lessons. The one main difference between the two stories—Concordia’s direct involvement.

Instead of using Bright International Student Service Inc.—as Xiao-Ming did—the students were put in touch with Peter Low, who was an official university recruitment agent at the time. For a fee of $2,200, Low would “fast-track” the application process and help sort immigration hurdles, but students would have to live in a homestay for at least two months. Some of this paperwork was exported to Low’s company Orchard Consultant Ltd., which—like BISSI—was located in B.C. Since the incident, the university said it hasn’t used any external recruitment agent or contracted work with Orchard Consultant Ltd.

1WEB_900_600_90.jpg)

_600_375_90_s_c1.jpg)

_600_375_90_s_c1.jpg)