Theatre Review: Black Boys Aims to Make its Audience Think

Play Based off Memories Surrounding the Actors’ Experience as Queer Black Men

At the beginning of the play, performer Stephen Jackman-Torkoff stated that the play we were about to see is a “spiritual experience.”

Black Boys is a piece of satirical and experimental theatre that explores the intersections of the queer experiences of three young Black men living in Toronto. The story is based off of the real life experiences of the actors, and taped and transcribed conversations between members of the SAGA Collectif. The play has been in development since 2013.

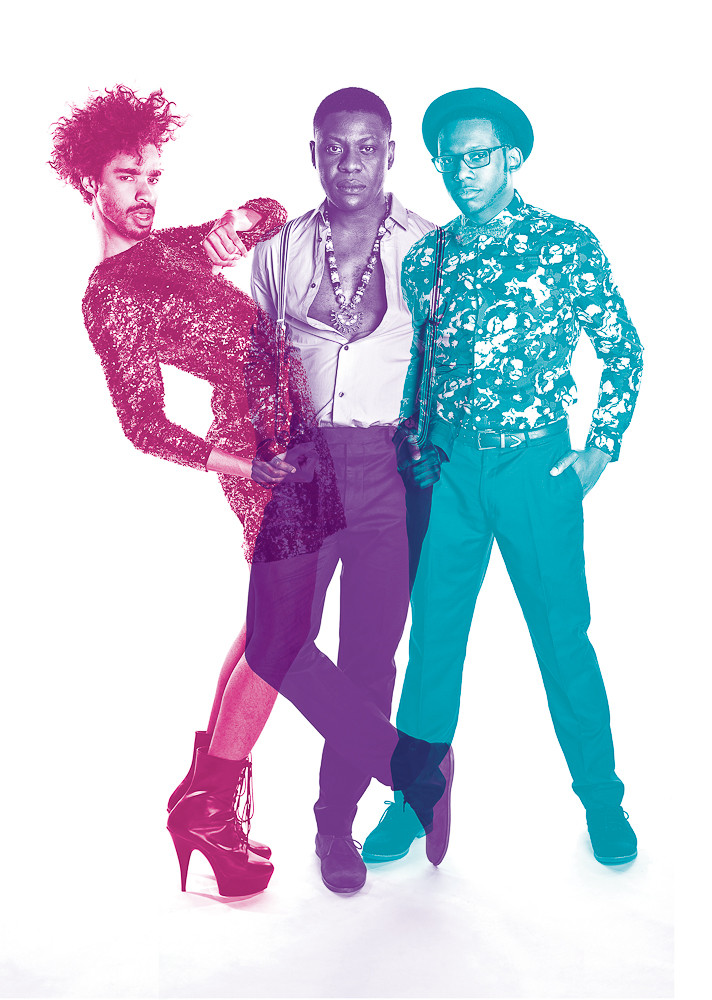

The performers are Jackman-Torkoff, Tawiah Ben-Eben M’Carthy, and Thomas Olajide, all of whom play themselves in the production. Virgilia Griffith choreographed the show while Jonathan Seinen directed it. The cast, Griffith, and Seinen are all members of the SAGA Collectif, a performance company.

The play addresses the differences between the actors’ shared experience of being queer Black men. It is a Buddies in Bad Times/SAGA Collectif show presented by Montreal’s Black Theatre Workshop and Espace Libre.

M’Carthy, a Ghanaian immigrant, did not identify as Black until arriving in Canada. He, like many Black men, was raised by his grandmother after his mother died and his father went to prison.

Jackman-Torkoff, a mixed race individual and formerly in foster care, did not legally have parents. He was adopted last year by two of his three white parents.

Lastly, Olajide, as the most “straight passing,” was raised by his grandmother after his father’s imprisonment and his mother’s death.

Griffith’s choreography helps to further distinguish the actor’s differences; M’Carthy is languid and large, Jackman-Torkoff is wild and uninhibited, and Olajide is powerful but contained.

All three are unafraid to express overt sexuality through their dancing.

While the performance was going on, French surtitles in white lettering were hanging above the stage from a black screen. The goal of creating a bilingual theatre experience was a new collaborative effort between Black Theatre Workshop and Espace Libre.

Sitting in the third row, it was nearly impossible for me to pay attention to what was happening onstage at the same time as reading the surtitles. I had to look back and forth rapidly, which is something that may inconvenience Francophones in the audience.

Sitting in the back might compromise the ability to see the emotions on the actor’s face as clearly, but would likely provide a comprehensive viewing experience.

The seats are open benches rather than individual chairs, and the space itself is hot and completely crowded with people. There weren’t many free seats and ushers had to ask people to squeeze together on the benches to make room for more people as it gets closer to 8.

The performance was a mixture of monologue, dance, and song, as well as meta-narratives that help explain production choices and give the audience more insight into the actors’ personalities, as well as the decisions that shaped the show’s content. For example, there was a scene in which M’Carthy is seen as the serious one in a debate surrounding Jackman-Torkoff’s banana skirt dance.

Some of the debates that occurred within the meta-narratives surrounded their varying shades of Blackness, whether or not they could pass as straight, thoughts on slavery and the song “Amazing Grace,” racial segregation in Toronto nightclubs, and when Black Lives Matter Toronto halted the Pride Parade in 2016 to make their demands heard.

There were five large moveable panels onstage which were used for various purposes, like projections of Olajide taking selfies while Jackman Torkoff presented a monologue about his going out ritual in the foreground.

The play began joyfully, as all three actors present their going out rituals amid shouts of “Hallelujah!” Jackman-Torkoff was completely nude less than 15 minutes into the show, expressing his emotional vulnerabilities through his physicality.

“Too soon?” he asked the audience playfully.

His varying costumes were the most visually interesting and diverse. One of his last outfits was a long, sparkling, blue spaghetti strap dress that he deemed too tight after a few minutes, unrolling it to the waist so that he could wear a faded white t-shirt instead.

There were small moments of audience participation, such as when Jackman-Torkoff asked the audience to yell out their best “Stella!” in imitation of Marlon Brando role in A Streetcar Named Desire.

At one point, Jackman-Torkoff requested that friend to join him onstage for a dance, explaining that he usually asks a willing stranger to volunteer but that his friend from middle school was in the audience and he wanted her to come and dance with him. This makes for a different experience with each performance of Black Boys as explained by Jackman-Torkoff.

Artistically speaking, it’s considerably easier to say everything you want, to explain every experience you’ve had and outline how it has shaped you, and how it connects to everything else that’s occurred in your life.

Black Boys doesn’t give in to those temptations. This show was powerful in its simplicity and what it chose not to say.

The reasons behind why Jackman-Torkoff needed to smoke three bowls a day to get through working at the Shaw Festival or why Olajide’s father went to prison ultimately seem irrelevant. Especially when considering the totality of the production.

What the audience gets to see has been carefully chosen, right down to the meta-narratives that help to explain the actor’s characters, which is especially important as they are playing versions of themselves.

By watching and absorbing the play, the viewer is provided with an emotionally rich experience that bypasses the need to have every pedantic detail fleshed out and provided for.

Black Boys addresses the actors’ existential questions, everyday concerns, and emotions with humour—such as Olijade’s realization that he was gay involving a fantasy of Mario Lopez— and gracefulness portrayed in the choreography.

As I left the theatre, it felt as though I’d been emotionally hit by a ton of bricks, but in the best way. By the end, every scene felt as though it was connected; what had felt fragmented at first came together as a whole beautifully.

To its credit, this play does not pretend it has all the answers. Rather, it demands that you end leaving with thoughts intended to make you question the assumptions you’d arrived with.

_600_375_90_s_c1.jpg)