The Many Shades of Strike

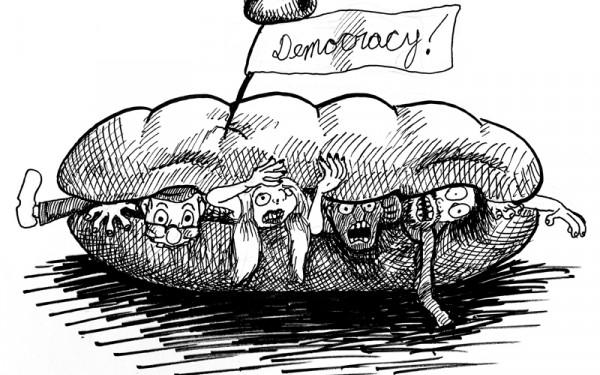

‘False Division’ on Campus

At the controversial Concordia Student Union General Assembly on March 7, two things happened: a minority of undergraduate students voted to strike against increasing tuition fees, and an anti-strike movement was born.

One of the groups against the strike tactics—who call themselves Concordia Students Against a Strike—took to the Internet to spread their message and mobilize. The membership of their Facebook group ballooned from 160 members to 1,400 over the weekend.

Taylor Green is a second-year urban planning student and spokesperson for CSAS. He maintains the CSU didn’t do a good enough job representing the many political positions of Concordia students.

“More than half of our group don’t want tuition hikes—we can agree on that point—but the strike tactics [the CSU] are employing were never discussed. They just weren’t,” said Green.

The group also takes issue with the low quorum required to pass union decisions, the way the faculty association and departmental GAs have been run and with the kind of information that’s been distributed.

While Green admitted he did not attend or vote in the March 7 GA, he said the group is not currently calling for a referendum.

Right now, Green said, it’s about information and “mobilizing the apathetic.”

“Where are the posters that say, ‘Hey, anyone have an opposing view?’ They never encouraged it. And while I think some of the onus is on people like me that are now speaking up about this, […] really the onus is on the CSU to make sure that there is some kind of involvement from all parties,” said Green, who admitted the Facebook group has become a “ridiculously huge open forum” for discussion.

Despite the differing opinions on how to mobilize as students moving forward, Green said he does believe that creative compromises can be reached on campus that will work for all parties.

He called the ideas of the CSAS moderate—maintaining that students’ right to go to class if they want to, or protest if they want to, ought to be respected.

Green also presented concrete “nine legal and completely plausible demonstration alternatives [to striking] that don’t involve the remainder of the student body, faculty or administration.” These included a hunger strike, sitting protest and vigils.

He has also begun circulating a document to faculty associations called the Hard Picket Address, which insists that students have the right to

attend classes.

Other factions of the anti-strike camp have also sprung up on Twitter, calling for the picketing of the CSU offices and a public debate with the CSU, though no concrete actions have been carried out on campus.

One vocally opposed anti-strike member, using the Twitter handle @StriketheStrike, agreed to an interview with The Link over the weekend, but did not respond to a follow-up by press time.

Beyond Concordia and online mobilization, organizations of students against a strike have also been cropping up on other university campuses as well.

Most famously, the Mouvement des étudiants socialement responsables du Québec, allegedly led by students associated with the youth wing of the Liberal Party, has been vocal about their position and was generated a lot of press attention.

Claiming to represent “neutral students” and the “silent majority,” the MESRQ made a huge splash in the media last February, especially when spokesperson Arielle Grenier went on French television talk show Tout le monde en parle.

More recently, the group has been vocally upset about the proliferation of red felt squares at the gala for this year’s Jutra awards, the annual celebration of Quebecois cinema.

Dozens of artists, filmmakers and producers in attendance—including the cast of the Best Foreign Film Oscar-nominated Monsieur Lazhar, which swept the awards show Saturday night with seven Jutras—wore the anti-tuition hike symbol to the black-tie event.

Another group, the Coalition étudiante pour l’association libre, also entered the fray earlier last week, looking to depoliticize student unions. CEPAL reportedly believes “a minority of students are holding [university] institutions hostage.”

At Concordia, at least so far, the issue isn’t just a question of black or white—or red or green.

“We should all be on the same side,” Green stressed, adding that the term ‘strike’ has falsely divided our campus. Green said he would like Concordia students to stop using the term ‘strike’ as well, because “it automatically polarizes people.”

“I personally don’t want to see anybody else not get the opportunity to go to school because of [the tuition increases], but I’m against the strike,” he said, adding that he believes blocking students from going to class is illegal.

“Listen, no one wants to see this tuition increase—we all have the same goal,” Green argued. “But we need to get serious. A strike is not serious.”

Green also said he was concerned the strike was pitting Concordia students against each other.

“The fight is not supposed to be against Concordia, or against other students,” he said. “The fight is against the government. Let’s bring it to the government.”

Today, the objection of students to the tuition increase is coming to a head after many years and tactics.

The first announcement of the tuition increase was released on April 1, 2010, and was followed by a demonstration against the hikes that saw both students and unions take to the street approximately 12,000 people strong.

Concrete alternative funding models for post-secondary education were then issued to the Ministry of Education in November 2010 before a consultation meeting in Quebec City Dec. 6 that saw students walk out in protest following failed negotiations.

Student lobbyists at the time argued that the meeting’s purpose was to legitimize the increase and its scale.

Proponents of a direct boycott of classes contend that, while alternative actions to striking are valuable, they would be most effective in the context of a strike where students are free to devote time and energy to the cause. Groups like the Concordia Mob Squad have argued that striking is, historically, the only strategy that has led to gains for students.

3_600_375_90_s_c1.jpg)

0webedit_600_375_90_s_c1.jpg)