The anime industry needs to stop hyper-sexualizing underaged girls

Dismantling the Hate Around the Anime ‘Sword Art Online’

The over-sexualization of teenage girls in anime is something that has long been accepted, even welcomed, but it is time to at least start the conversation as to why that is unacceptable.

Everyone has something they love to do and hyper-fixate on, which means everyone is or has been in a community of some sort.

It does not matter if you are super into bikes and know everything about them or if you are a hardcore fan of soul music. Every single community will have its own infamously hated thing that is bashed by the majority of its consumers.

In the anime community, said infamously hated thing is the animated tv show Sword Art Online or SAO for short. Initially published in 2009 as a Japanese light novel, which is a young adult novel, the world of Sword Art Online was turned into an animated show in 2012, and is still going strong, as the fourth season came out in 2020.

Every story needs a hero and SAO’s hero is 14-year-old Kirito, who is later joined by the lead female character, and main love interest, 15-year-old Asuna.

Part one of the show’s first season introduces the viewer to a world where virtual reality has transcended its limits, allowing players to fully immerse themselves in a virtual fantasy world, using only their minds to control their avatars. The story complicates when, after the first official launch of the game, named Aincrad, the creator explains that the players are trapped in this virtual world.To escape, the players have to complete the 100 levels of the game, with the added cruel twist that if the players die in-game, they also die in real life.

To better understand how disliked this series is by veteran anime watchers, it can be seen as the equivalent of what Twilight is to the book and film communities: a massively popular series with an international fanbase of people who love to hate it. Disliking it has simply become the norm.

SAO is the sort of media one decides to indulge in, once in a while, whether for the sake of nostalgia, or like me, because they decided to end an already bad day by torturing themselves a little bit more. After years of not watching the series, this re-watch of SAO made me remember why it truly is a terrible show.

Despite the anime’s many flaws, such as overall characterization, plot, and overused tropes, SAO’s biggest fault lies in the portrayal of its female characters, more specifically, the unnecessary over-sexualization of young girls.

Most action and fantasy animes, the ones catered to boys to be blunt, will showcase a certain amount of fan-service to please its male audience. Fan-service is the act of inserting salacious shots of a character, whether female or male, for the entertainment of the viewers. For a more general audience though, and for an anime that is not for mature audiences, like SAO, this generally means showing a panty shot here and there, or depicting a 16-year-old girl in her underwear.

The anime industry has had a long and complicated history with the hyper-sexualization of young girls—a topic too wide to be covered to its fullest right now. Amongst other depictions of this topic, the ever-popular ‘brocon’ and ‘siscon’ sub-genres, which are shorter terms for “brother complex” and “sister complex,” are one of the most popular categories when it comes to the sexualization of young girls in media. These categories depict either the older or younger sibling being romantically obsessed with a brother or sister figure. Considering SAO’s involvement with this topic, I will focus on one specific topic concerning the over-sexualization of young girls in anime: lolis.

The term ‘loli’ refers to the Japanese sub-genre of portraying young-looking girls in a sometimes erotic way in anime and manga, with an emphasis on cuteness. They are a widely accepted subculture within the anime community. Lolis have even become a meme of sorts, seeing how they are an easy trap to fall into, because of their cute and youngish appearances. Lolis can be divided into a number of sub-categories, the loli spectrum ranging from one extreme to the other. There is the young and bashful, sister-like, girl one loves to make fun of and take care of. Whereas there is also the adult who is pushing forty, but is given the body of a 12-year-old child, typically behaving like one. Lolis remain a controversial topic, especially when paired with fan-service. This then creates the lolicon complex, which is characterized by an attraction to underage anime characters, especially young looking girls. The lolicon complex is heavily depicted in the character of Silica.

Silica, who is 12 years old when Kirito first meets her, immediately fits the first category of the loli formula, with her pigtails and dependent behaviour, she embodies the role of a young girl one wants to take care of. The show compares her to Kirito’s younger sister, associating her character with the idea that she is to be seen as a little sister figure. Her portrayal could have stayed within the cute girl range, with nothing too raunchy added to her character, but the producers of the show decided that, unfortunately, that was not enough.

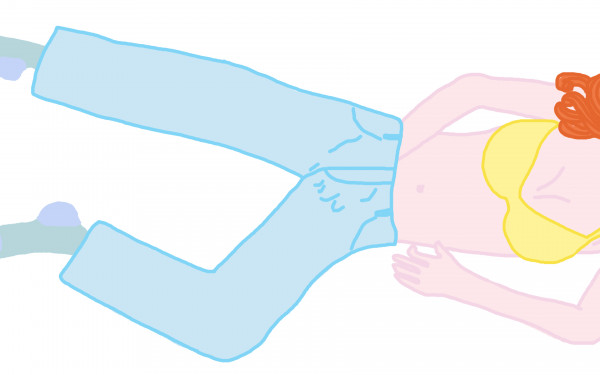

In one particular scene, after Kirito and Silica separate to their own rooms for the night, we are given a shot of the young girl laying on her bed, in underwear. A character’s colour scheme is one of the first things one can study, when analyzing a character. Silica’s underwear being white, with pink lining, can be seen as a representation of the male gaze to preserve women’s, especially young girls’, purity. The colour white emphasizes virtue, while at the same time preserving femininity and sensuality, depicted through the colour pink.

Although colour theory in character design is an interesting subject, the more important question at hand is: what need was there to portray a 12-year-old girl in her underwear?

Showcasing a prepubescent girl in such a vulnerable state only serves to perpetuate the idea that women’s only purpose is to be seen as a sexual object.

Showcasing a prepubescent girl in such a vulnerable state only serves to perpetuate the idea that women’s only purpose is to be seen as a sexual object. It plants the idea in young girls’ heads that to be seen as valuable from an outside perspective, they must behave and dress a certain way.

This type of fan-service is directed towards young boys as well as grown men attracted to the anime's sister complex, which is where the real problem lies. By depicting her in such a vulnerable position, SAO’s portrayal of Silica promotes the fetishization of young girls. This specific scene shows a complete disregard for young girls’ safety and privacy. It ultimately tells young girls that their existence is no better than the sexual fantasies men make of them, which in turn teaches young boys that such behaviour is okay.

This scene also shows the gender inequality that still exists between girls and boys, and the way they are each so differently depicted in the media. It is a missed opportunity for equal representation of young kids who like to play video games, no matter their sex.

This also creates a form of entitlement from certain groups of people, who think they are entitled to this type of content. in real life, boundaries between fiction and reality are crossed, making a number of young girls who like anime uncomfortable and unable to truly enjoy being in the community.

Asuna’s character, who is the lead female role, is not treated much better. She suffers the unnecessary emotional trauma inserted in her characterization. It eroticizes and romanticizes the sexual assault her character had to go through for the sake of “character development” and for the sake of shock-value paired with a side of fan-service.

The second part of SAO brings us to the second part of the season, where after two years of being trapped in the game Aincrad, Kirito and Asuna defeat the game and return to the real world. In true anime hero fashion, Kirito’s first thought is to go meet Asuna and declare his love for her in real life, which we quickly find is unfeasible as Asuna never woke up. We learn that she is being held captive in a birdcage, in a completely different game, by the second arc’s main antagonist, Sugou.

Set to marry Asuna in the real world, because of her high-class status, Sugou’s plan was to marry her unconscious body, to then have her wake up married to him. As if such a plan and keeping a teenage girl chained in a cage were not enough red flags to warn you away from this anime, Sugou’s behaviour, which worsens over the course of the show, surely will.

During a culminating moment of the anime, Sugou explicitly explains to a helpless Asuna his intent to record a video of him virtually raping her, to then play it back in the real world at the same time as he sexually assaults her comatose body. During this specific scene, we see him not only tear apart Asuna’s dress, revealing her bare chest in a way that is still PG-13 friendly, but we also see him lick her all over and fondling her in inappropriate places.

This scene is disgusting and was incredibly hard to watch back, as it is clearly not a scene created to start a conversation, but mostly to create a shock-factor that makes the viewer say “hey I hate that guy!” This type of narrative, where women, in this case, a teenage girl, suffer any type of sexual assault is nothing new. It’s a vastly overused trope that, most of the time, has no purpose but to create a climactic moment for the protagonist to reach finality in a story.

Fortunately, Sugou’s plan never came to fruition but this type of sexually violent, and frankly void of meaning, portrayal of young girls is something that the public has been desensitized to a point, where a scene such as this one has been forgotten by its community.

SAO is known for being juvenile and failing to have a consistent plot-line, but it is scenes like these that remind me why the show is more than just bad. Its depiction of young girls is damaging not only because of the mistreatment of its lead female character, purely for entertainment, said amusement is catered towards grown men who thrive off of this type of representation.

This scene only serves to remind me that there are people who enjoy seeing women in a position of helplessness and pure fear, and that will always end up being more damaging than helpful.

The anime community has its fair share of gore and some of its best animated works depict complicated stories that deal with trauma and open conversation, which is where the difference lies with this specific show. The intention and the execution of Asuna’s story are not comparable to the characterization of women offered in films like Paprika and Perfect Blue.