The R-word

Sexual Assault Awareness month teaches women how to stay safe

They say you always remember your first time. That is especially true when you lose your virginity — not to a high school sweetheart or some stupid drunken fling — but to a rapist.

This happened to Anna, who chose to keep her last name anonymous to protect her identity. She was 17 when she was raped after being drunkenly led away from her friends at a party.

Despite the trauma, Anna, now 24, never reported the crime.

“Honestly, I wish I had, looking back. I really do. I just didn’t want my parents to be disappointed in me. Disappointed that I was drinking underage, that I snuck into a party, that I lied about where I’d been and—obviously—that I’d been seriously taken advantage of,” she said.

“I should have filed a report, but I was way too shamed. Total shame. I didn’t want to relive it,” she recounted. “[The nurse who performed a rape exam] told me that he had raped me so hard she’d found blades of grass and bits of dirt up my ass. I didn’t want anyone to see pictures or that little baggy of grass as evidence.”

Not alone

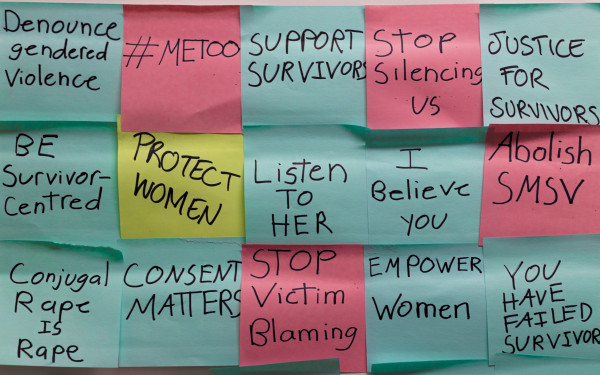

The month of April marks the second annual Sexual Assault Awareness month, dedicated to abolishing the myths that surround violent sexual acts, raising public consciousness of the frequency of these crimes and ensuring that those who experience assault know the resources at their disposal.

One of those resources is Diana Yaros, a community worker at the Mouvement contre le viol et l’inceste, a support group for the victims of sexual assault. She said that the first step in combating these crimes is making the public aware of the dangers and ensuring they understand that the only person who should control their bodies are themselves.

Anna is not alone. One of the most well-known statistics about sexual crimes is that only one in 10 gets reported.

Yaros testifies that the number is accurate, but points out something equally unsettling — the consistency of the statistic over time.

“That’s a frequently quoted statistic, but I think it’s probably correct within 1 or 2 percentage points,” she said. “That statistic has been around for over 35 years.”

According to Yaros, part of what contributes to a person finding themselves in a sexually vulnerable position is not knowing how to express their needs, wants and limits.

“Communicating what they are agreeing to [sexually], what they are not agreeing to, what constitutes consent” are the keys to maintaining control, she said.

“Women think they are communicating non-consent, and men aren’t getting the message.”

The truth is that most crimes are not reported because not only are the victims usually too ashamed to come forward, but they also are often the most marginalized members of society: the young. Combined with the fact that most rapes and other crimes are committed by somebody the victim knows and trusts, there is a strong incentive to not make waves.

“The majority of sexual assaults are committed by someone you know,” explained Yaros. “Over 50 per cent of sexual assaults happen to minors, [or those] under 18 years old.”

Dr. Chantal Maillé, an associate professor at Concordia’s Simone de Beauvoir Institute, noted that society’s conservative views on sex and drug use has also put those on the fringe at risk.

“Many people who it happens to are on the margins, like drug users and sex workers—they’re very good targets for sexual assault,” she said. “They can’t report it and it might happen just on the street.”

“In a lot of ways I don’t think I’ve dealt with it fully. I don’t know if I ever can…”

Sex, sexuallity and stigma

Since the emergence of the anti-sexual assault movement in the 70s, much progress has been made at making the public aware of the trauma of sexual assaults. Victims are now able to speak out and much of the stigma of being a victim has disappeared.

“There has been some progress. We’re not at the same place we were 35 years ago,” said Yanos. “[Back then], a woman couldn’t accuse her husband of rape, or she could be accused in court of provoking the assault.”

Progress can also be traced back to the work of the feminist movement, said Maillé.

Because of the gains women have made in society, rape and other sex crimes have been recognized as different from other forms of violence. Feminist theory was the first to communicate the idea that rape is not entirely about sexual pleasure, but also about establishing dominance.

“The idea of sexual assault appeared as an issue because of the work of feminists. We owe it to them the idea of theorizing and bringing awareness to the specificity of sexual assault,” noted Maillé. “In the 70s, radical feminists expressed the thought that sexual assaults were not an expression of sexuality, but of power.”

Still, there is controversy in the movement. According to Yanos, many feminist theorists argue that the root of sexual violence can be traced to a society that teaches a very particular pattern of sexual relationships. The pervasiveness of sexual images, specifically an abundance of pornography, has theorists disagreeing on the understanding of sexuality and the ways in which to express it.

Yanos argued that the often-misogynistic images associated with porn sets a tone that leads to confusion over what is appropriate when engaging in sexual activity.

“I would say that there is an influence — not cause and effect, but I do think that it plays a role in creating the context, and creating a sexual environment and banalization of sexual assault,” said Yanos.

Maillé disagreed, observing that pornography can offer a release for the sexually frustrated and an outlet for urges that might be otherwise repressed. If used properly, she contended, porn can be a tool to educate the population on sexual matters.

“[I think] that if you let people engage in different forms of sexual fantasies, including pornography and access to sex workers, it can reduce frustration and repression,” she explained. “Pornography could be a form of education for sexuality. You have all kinds of pornography and more and more feminists are involved in it. The idea that pornography is only negative is an idea that has been challenged.”

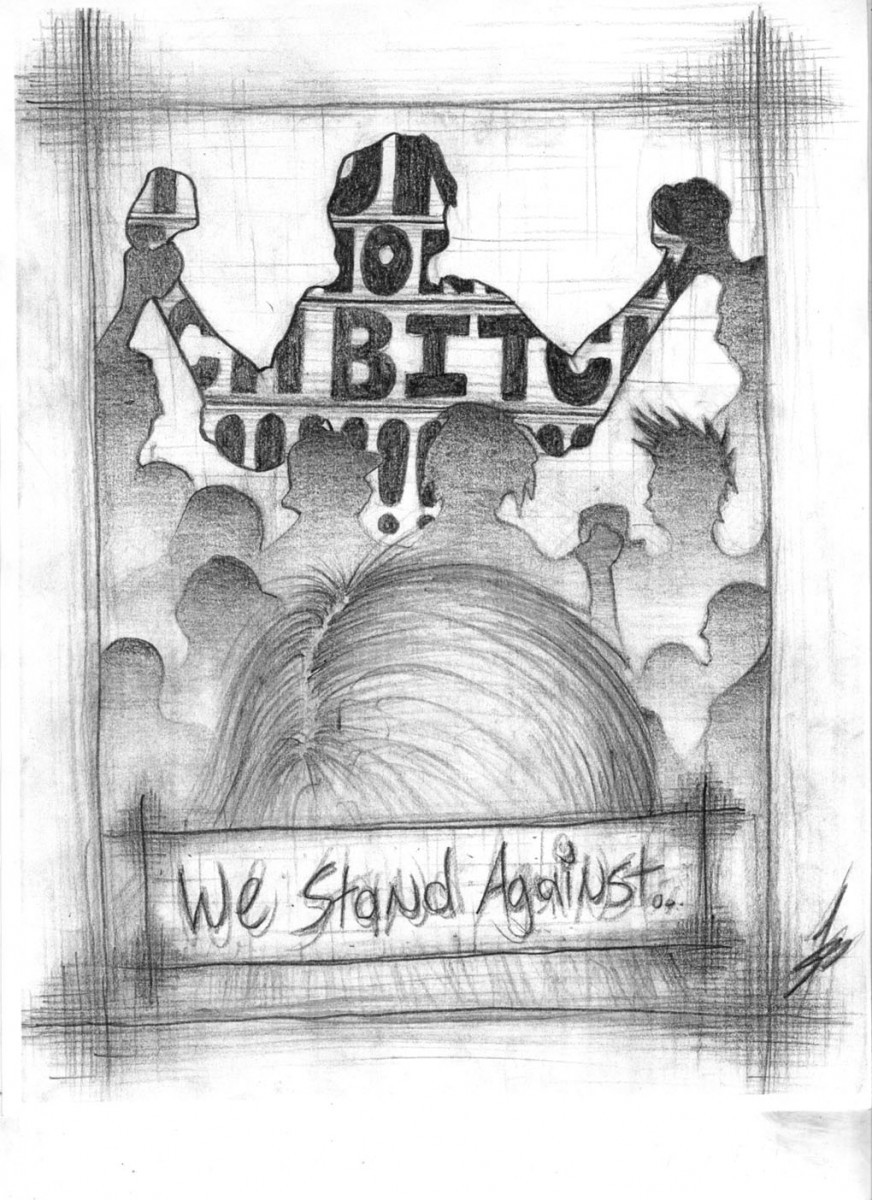

Break the silence

Most dialogue on sexual violence has portrayed men as the perpetrators and women as the victims. As the scope of the crimes of priests in the Catholic Church comes to light, more focus is being placed not on the role of gender in these crimes, but on the violation of trust.

“The construct of sexual assault where women are victimized and men are the abusers needs to be expanded,” explained Maillé. “There are other models of sexual assault.”

Whether man, woman or child, the trauma of a sexual assault is the most intimate kind of violation. To have one’s own body invaded by another person is traumatic for anybody. Yaros says that while individual reactions differ, it is always a major source of pain.

“It depends on the resilience of the person, but it could be anger, fear, an extreme feeling of invasion, to feel like you have no control over something as basic as your own physical integrity,” she said.

Perhaps the best advice is to always remember that your body is yours, and yours alone. There is no excuse or justification for a violation of that sanctity.

Anna acknowledged that getting past pain and working through shame is a battle in itself, and one that may take her entire life.

“In a lot of ways I don’t think I’ve dealt with it fully. I don’t know if I ever can. I mean how do you get over something like that?” she asked, sighing deeply. “I think I’ve channelled it in other ways, [but] it’s always going to be a part of me.”

Sexual assault and the victim’s rights, are certainly something people should be more aware of, she continued.

“Don’t just do nothing. Tell someone. I know how badly it hurts, how vulnerable you can feel, how dirty and fucking awful it is and how difficult it can be to look at yourself in the mirror and say ‘this isn’t my fault’ but it really, really isn’t.”

If you or someone you know has been the victim of a sexual assault, contact:

Mouvement contre le viol et l’inceste

211, Succ. De Lorimier

mcvi@contreleviol.org

(514) 278-9383

You can reach Concordia’s Counselling and Psychological Services department at:

Sir George Williams Campus

H-440

1455 De Maisonneuve Blvd. W.

(514) 848-2424 ext. 3545

or

Loyola Campus

7141 Sherbrooke St. W.

Administration Building Room 103

848-2424, ext. 3555

This article originally appeared in Volume 30, Issue 29, published April 6, 2010.

web__600_375_90_s_c1.jpg)