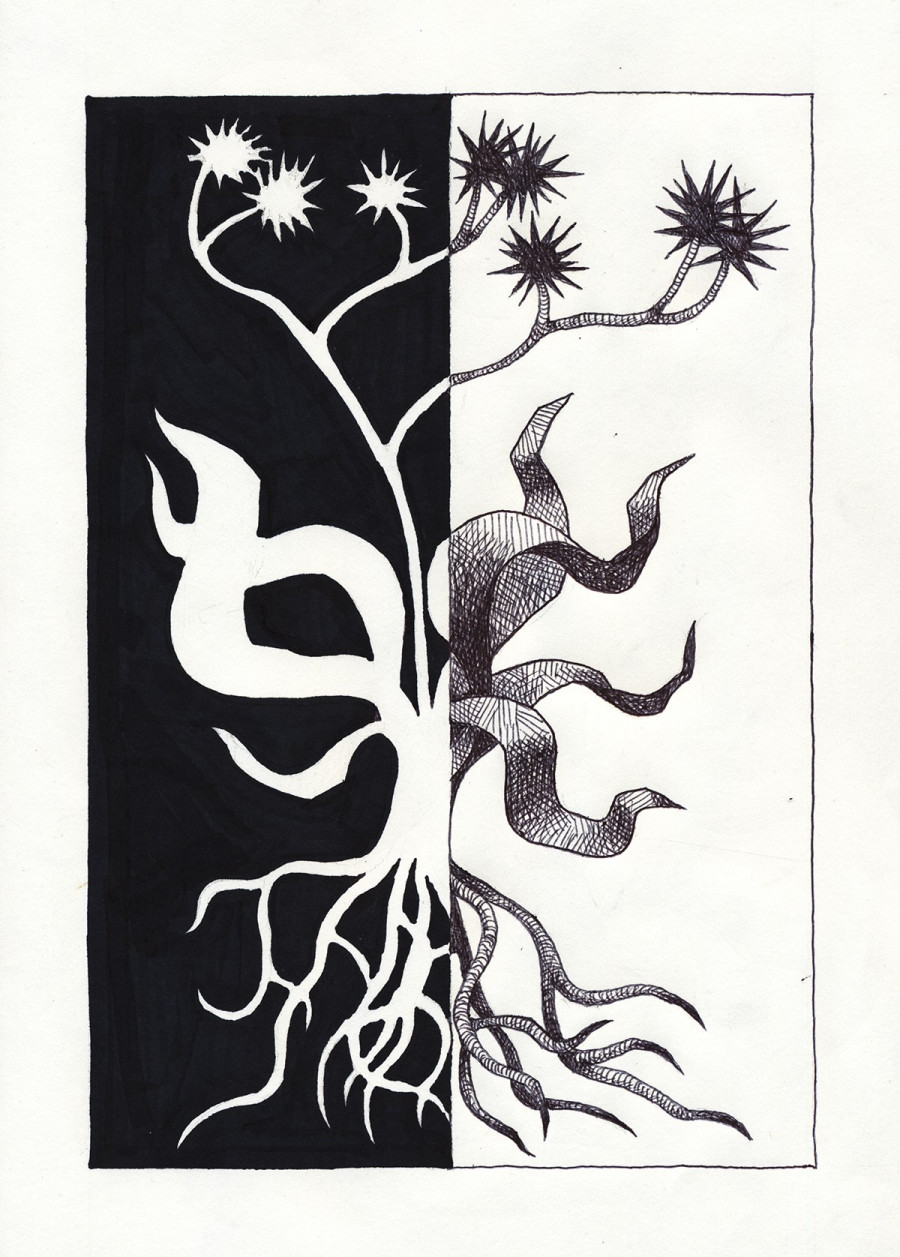

Special Issue: Split Identity

My father is white. He has twinkly blue Kris Kringle eyes. The older I get, the more likely we are to be mistaken for a couple. This doesn’t happen to my younger sister, whose freckles, pale eyes and pinkish skin match our father’s.

My mother is Pakistani. Her eyes are the colour of milk chocolate. People often remark that we look alike. I’ve never agreed. At 13, I once asked her why.

“We don’t really look alike. You look less white than your sisters do, and there’s a silence to fill after anyone remarks that they look so much like your Dad,” my Mom said.

As a child, I always felt more at ease around my mother’s side of the family because they looked more like me. I felt as though I belonged to them in a deeper, more instinctive way. I didn’t understand that I wasn’t a brown person until grade one.

My skin is pale and olive toned. I have dark hair and eyes. I thought that was the distinction between white and brown people—hair and eye colour. It seemed like I was the same as my mom and different from my blue-eyed Dad and his family. My sister used to call me “poo eyes.” I couldn’t think of anything mean to say back, because I was deeply jealous of her celery-coloured irises.

When I was little, I was obsessed with matching. My family is a mosaic of shades, from pale pink to the colour of burnt butter. When I first heard the stork-drops-off-the-baby story, I thought maybe I had done something wrong to get stuck with my patchwork family instead of a nice matching one. I thought that being the same was the best thing to be.

Growing up mixed made me feel embarrassed and conspicuous, as though I’d gotten to class in the middle of a test. Even well meaning statements that mixed people were more beautiful made me feel like the glaring exception.

I met Miriam when we were both acne-faced 13-year-olds. Our shared experience of being mixed was one of the first things we bonded over.

When Miriam, who is white and Bengali, was six years old, she went travelling with her mother and her older sister. They are both pale and freckled, whereas Miriam has her father’s walnut complexion. At the airport, security asked whether she was with them, whether she was really her mother’s daughter. Because she was mixed, people didn’t think she belonged to her own mom.

“I’ve always felt a bit different in my family,” Miriam told me. “It’s something I think about less, but when my sister and I go out for drinks, I’m still hyperaware that people think we’re friends and don’t think we’re sisters.”

Shakti, another friend of mine, has big curly hair and also grew up self-conscious of her “weird” name. When we met, she asked me if I was mixed almost right away. That kind of bluntness never bothers me if it comes from another mixed person.

“I grew up with my dad who is white but he always made sure that I knew about the other side of my culture […] he also made sure I spoke Spanish well,” she said.

Shakti grew up in a small town in Quebec, where her brown skin and curls made her an anomaly. “As a child I wanted to be white,” Shakti said. “I wanted nothing to do with my other side.”

One afternoon, in elementary school, Shakti’s mother came to pick her up. This was the first time her classmates had seen her Dominican mother.

After seeing her mom, the kids in her class began calling her a “Negress” and using the N-word. It wasn’t until she turned 12 and moved to Montreal that she became surrounded by diversity and started exploring what it means to be white, Dominican and Shakti.

“Research shows that even in places where multiracial persons are common, such as in the United States, this identity and its relation to the way race is commonly practiced present psychological and social challenges for multiracial persons,” writes Ronald Sundstrom, an African-American studies professor at the University of San Francisco.

At age 11, I heard Cher’s “Half Breed” for the first time. In the song, she sings: My father married a pure Cherokee/My mother’s people were ashamed of me/The Indians said I was white by law/The White Man always called me “Indian Squaw.

That was the first time I had ever heard anyone express negativity towards being biracial. “Colourblindness” had been perkily parroted by teachers for years, but I had noticed the difference between my family and my friends’ families. I went to elementary school in a wealthy area. Everyone had two white blond parents and a ski cabin in Mont-Tremblant.

“So much attention is given to mixed-race looks that some multiracial individuals experience being reduced to the very fact of their being mixed; they are treated as embodiments of the sexual crossing of racial boundaries and taboos,” professor Sundstrom writes.

We’re living in a time where an unprecedented amount of thought is being devoted to identities, especially those of marginalized populations. It’s hard to define where mixed people fit into that. A common thread that ran through the experiences of those I interviewed—as well as my own—is

that our experiences of racism have been covert. That can lead one to question whether one’s experience was real.

I often feel as though I have to prove myself to people of colour. Show that I’m not an unaware racist white person, I’m something, I’m closer to what they are, I’m on the same side even if I might not look like it. I’m overcompensating.