Remembering Concordia’s Computer Riot

The Time the Ninth Floor Was on Fire

The Sir George Incident. The Computer Incident. The Computer Riot. No matter the name given to it, it is one of the most well known events in the history of student activism at Concordia.

Feb. 11 will mark the 50-year-anniversary of the Computer Riot, the sit-in against discrimination that escalated, for reasons that still are not clear, into the destruction of the Hall Building computer labs.

The event has had a profound and permanent impact on important aspects of student life, while also giving Concordia the reputation of being a hotbed for student activism.

It all started in the spring of 1968. Six Caribbean students accused their biology professor of racism after receiving lower grades than the white students in their class, for the same calibre of work. Because of a lack of communication and what has been described as a ‘’mishandling of the situation’’ by the administration, the students who launched the complaint believed they were being given the runaround.

During the fall semester, sit-ins and peaceful demonstrations were growing more and more frequent, and more and more students were showing their support against discrimination. By December, a hearing committee was to be put in place to hear the accusations, but disagreements between the administration and the students on the terms of the hearing lead to their continued delay. In the end, a new hearing committee met on Jan. 29, but disagreements led hundreds of students to walk out in protest.

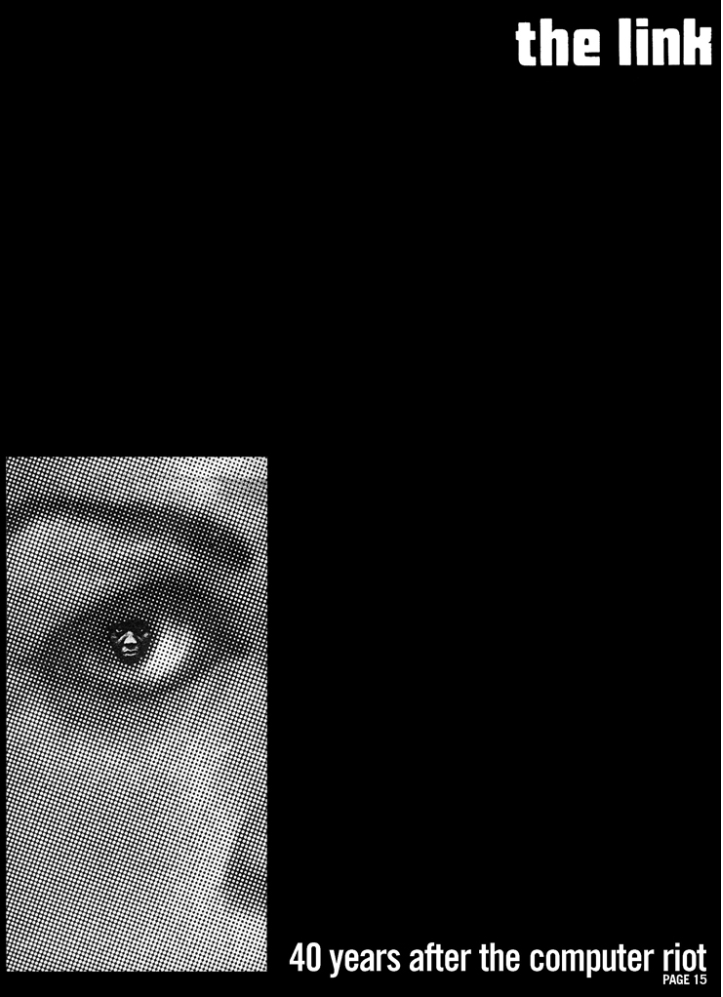

The Georgian— one of The Link’s predecessors—issued “The Black Georgian,” an edition of the student-run newspaper that gave Black students editorial control to express their concerns with the situation. The issue, with its entirely black cover, save for an eye with a face instead of a pupil, was released Tuesday, Jan. 28, 1969. The next day, the occupation of the ninth floor computer labs began.

The staff of The Georgian found their office padlocked and guarded by the RCMP. Most copies were seized and presumably destroyed, and the editor at the time was forced by the Day Student Association (one of the many precursor bodies of Concordia’s Student Union) to resign, and The Georgian was shut down entirely.

While it reopened and published some articles later in the semester, most of the staff prior to the publication of The Black Georgian were not involved. Years after the fact, David Bowman, the editor at the time, recalled years later that ‘’The Georgian was not the free press we thought it was. We were told the publication of the newspaper was a privilege, not a right and for abusing that right, we were shut down.”

“The Georgian was not the free press we thought it was. We were told the publication of the newspaper was a privilege, not a right and for abusing that right, we were shut down.”–David Bowman, former editor of The Georgian

On Feb. 11, all hell broke loose. A fire, the source of which is muddled at best due to the passage of time and the disparity of stories from people who claimed to be there, broke out in the ninth floor computer lab. The students who were occupying the building had barricaded themselves, and disgruntlement turned to violence, as student groups fought against each other on Mackay Street.

The riot squad of the Montreal police, and over 100 firefighters, stormed the building and 79 people were arrested.

The computers, not at all like the sleek machines of today or even the bulky beige-white PCs of the late 1990s and early 2000s, were almost the size of entire rooms, and employed punch cards to calculate algorithms and perform equations too complicated to write out by hand. When the smoke cleared, these computers were destroyed.

The destruction cost the university $2 million—over $13 million adjusted to inflation. The whole incident, as well as the legal proceedings of those who were tried, lingered for more than a decade.

For years, many—including Concordia’s administration—distanced themselves or avoided talking about what had happened, often downplaying their involvement whenever they did talk about it. Even 20 years after the fact, as was documented by a special feature in The Link, the administration didn’t want anything to do with what had happened,

Many of the participants, some of whom went on to have illustrious careers in politics, medecine, engineering, and so on, are now retired, or have since passed away. If they are still alive, they are now in their early 70s, and most definitely no longer in the limelight or as active in the communities they were involved in years ago.

Having the documentation on the Computer Riot in Concordia’s archives is what has permitted many to write about what happened almost 50 years ago. That’s why archival work and keeping tabs and records on what has happened is so important; not only for people looking to do research, but also to get a better picture of why things happened, and why they are the way they are today.

While a lot has changed in 50 years, elements of the Computer Riot and the events leading up to it still linger today. While the ability to air grievances with the school now exists in an official capacity, many still feel like their voices aren’t being heard, like those who have been vic- tims of sexual violence on campus. Concordia has also kept a reputation as an important part of activism within and beyond the school, and will more than likely continue to have this reputation 50 years from now.

Some things change, some things are eerily similar, but at the end of the day, the now legendary events that happened almost 50 years ago will live on.

Without the Computer Riots, Concordia would not be the same as it is today. That’s the beauty of history, not only does it let us remember the past, it helps us see where our present—and our future—comes from.

_600_375_90_s_c1.jpg)

_600_375_90_s_c1.jpg)