Blackout Sets the Record Straight On Concordia’s Computer Riot

Play Examines What Happened Before and After the “Riot”

Behind a backdrop of 1960s-style compact cubes, Blackout retold the history of Concordia’s infamous “Sir George Williams Affair” with unequivocal faith that students were not the ones who set the fire.

“We knew we weren’t going to try and make a nuanced piece of theatre where we’re going to present both-sides,” said Director and Co-Writer Mathieu Murphy-Perron. “Why would anyone start a fire if you have no way out?”

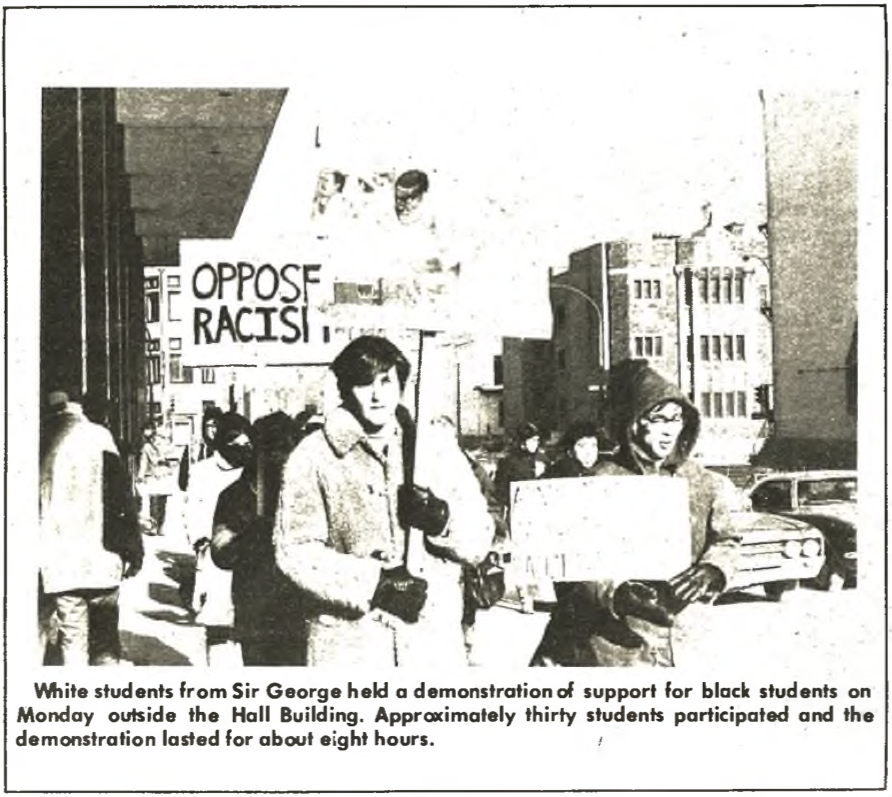

Feb. 11 will mark the 50 year anniversary of the so called “Computer Riot,” a student occupation of the ninth-floor computer centre in the Hall Building. It followed after persistent organizing against racism on campus, and the occupation later denigrated into a fire resulting in destruction worth $2 million.

Related

Remembering Concordia’s Computer Riot

On stage, a cast of students in a state of panic described how millions of punch cards fell like snow from broken windows, as smoke rose amid screams from the streets of “Burn! Burn! Burn!”

“They dared to ask who’s really in charge,” they said, with lifted fists in the air.

Much of the affair has been summed up through the events that unfolded that day in 1969, but students promptly corrected that perspective.“This story begins in April 1968, but it could also be 2018, 1989 or 1734,” students said. “It could just have easily be at any other esteemed institution of higher learning.”

“This story begins in April 1968, but it could have been whenever. It could have been any other institution.”

Soon after, students revealed where things really began: when Black students in the same biology class started to compare their grades to those of their white colleagues. Some wondered if they were handing in poor coursework, while others were sure it came down to race. Their uncertainties were later dropped once identical course work showed a white student had received 90 per cent for work that a Black student only got 68 per cent for.

Rather than amplifying that day, Blackout instead examined everything leading up to the occupation; how the teacher accused of racism was never dismissed, how the administration mishandled hearings into the complaints, and how secret minutes from administration meetings expressed “fear of Black violence” and a need to protect Concordia’s most valuable asset: its computer centre.

“It was very important to us to take back the narrative,” explained Lydie Dubuisson, one of the eight playwrights.“Through our research we realized everything was about the riot.”

Blackout also explored how students’ involvement in the occupation affected them afterwards: with arson charges, deportations, and in one instance, a fatal concussion. “That part of the story is less sexy than the occupation,” Murphy-Perron explained, but those parts are also more important.

“We wanted to show how you don’t end up in a situation like this for no reason,” said Dubuisson. “There must have been a reason, so let’s look at that—or do we really just want to ignore that and ignore the past?”

Beyond aiming to set the record straight, the play was also a call to action. “Stories of resistance must be passed on if we are to hope that future generations [will] be mentally, strategically and artistically equipped to challenge systems that seek to isolate and divide us; stripping us of our individual and collective power in the process,” wrote Murphy-Perron in pamphlet to viewers.

A chorus of four ancestors, in traditional clothing of the Nigerian Yorùbá people, helped students along in their fight, listening throughout and uplifting them through challenges faced. While reading out the names of students involved in the occupation, the cast of students later took on that role towards the audience, showing the same support to those in the audience.

“My voice joins with my ancestors,” they said. “Though many won’t hear, some will listen.”

“I hope it helped also the actors who had main lines, because it was not an easy process,” Dubuisson said. “It was our way to remind them of that support on stage, as much as it’s also poetic support, ancestral support [and] spiritual support.”

With the recent news that Concordia dropped sexual harassment complaints against a teacher without ever notifying the students involved, Murphy-Perron and Dubuisson said they couldn’t help but notice how the administrations’ mishandling of this complaint is reminiscent to their handling of 1968 complaints.

“Concordia right now is sort of going through a similar situation. Did they respond well to a complaint? Did they not respond well? Blackout is a way to have a reflection on that, it’s also about bringing more proof about something that is felt,” Dubuisson said. “How do we prove these things? And that’s not only a racial problem, but that’s also a #MeToo problem.”

“The office of the ombudsman was created afterwards and Canada’s multicultural policy came in shortly thereafter. These were mechanisms that were put in place to try and prevent matters like this from happening, but power will always find a way to circumvent those mechanisms,” explained Murphy-Perron. “It’s also our responsibility to say, ‘We see you circumventing.’”

The last showing of Blackout runs on Feb. 10 at 2 p.m. at the D.B. Clarke Theatre. Tickets are likely to sell out.

__600_375_s_c1.png)