Recruiting in University Sports

How Coaches and Scouts Build Their Teams

Concordia’s varsity teams played in 127 regular season games last year, not counting preseason competition, playoffs and tournament games.

Through a full year of games, a lot happens. Athletes and programs go through highs and lows, jobs are won and lost, and champions are named.

Regardless of the sport, all of this excitement begins in the same place. Each team starts to build towards their program’s success (or failure) in the same way.

“If you want to have a successful program, it starts with recruiting,” said men’s hockey head coach Marc-André Élement. “It starts with bringing the right guys and the right attitudes into your program.”

Recruiting is the base of every university sports program. From scouting athletes around Canada and the United States, to trying to get potential players to commit as student-athletes, it’s a process that’s a lot more than simply liking the way an athlete across town plays and getting them to a sign a letter of intent that ties a player to a university team.

It all starts with scouting. Scouts and coaches spend hours watching junior and CEGEP level players and try to identify a: who has the kind of talent they like, b: who is the kind of person they want on their team, and c: who is going to have a blend of a and b while wanting to enter the university level.

Concordia men’s hockey head scout Justin Shemie spent time as a scout for the Quebec Major Junior Hockey League’s Moncton Wildcats, so he knows how to evaluate players. He understands just how important it is to evaluate the kind of person a player is before bringing them onto the team.

“It’s a lot of information collection I would say,” said Shemie. Once he identifies a player he likes, it becomes a matter of talking to everyone around the player and finding out what he can expect off the ice as well as on it.

Shemie and Élement then break down a list of the players that check off the boxes they’re looking for, sort it by team needs, and start talking to players to build a relationship long before they become Stingers.

Despite that process, the player that they have on their list may not be the same player they see two years down the road.

Jorge Sanchez, former head coach of Concordia’s women’s soccer team, did most of his own scouting in his 16 years as coach. For him, the prediction aspect of scouting was tricky.

“You look at a 17-year-old, trying to figure out how good they’re going to be at 21. To me, it’s a feel,” said Sanchez.

It’s not as simple as just looking for talent. Will a player continue to develop, or will they plateau at 19? Will they be able to handle the heavy workload of classes while playing in a highly competitive environment?

With athletes spending a maximum of five years with the Stingers, being able to predict development is a must.

Recruiters have plenty of tools at their disposal to evaluate talent, though. They can scout players during their seasons, but there are more and more ways for players to show off for recruiters.

There are soccer showcases attended heavily by Canadian and American scouts, online highlight packages that players and agents can put together along with personal recruiting websites for individual players.

It’s a long way from 15 years ago when Sanchez would have low-quality DVDs mailed to him.

Coaches and scouts also rely on a web of contacts that see players that they can’t. The Stingers men’s hockey team brought in several players that played junior hockey out West or NCAA hockey in the United States.

It’s not feasible for a coach to be out that far during the season, so they rely on a blend of video and trusted advisors that can tell them who a potential Stinger is as a person and as a player.

Amidst all of this, the scope of the recruiting process in terms of time starts to become apparent.

“In a perfect world it’s an 18 month process,” said Sanchez, noting that it’s different for each player. That gave Sanchez time to see the player play with their schools, club teams, and eventually talk them into coming to play for him.

That kind of timeline suits a scout like Shemie just fine. The head scout believes that the best approach is a long term one that lets the player build a strong relationship with the team.

He started talking to Bradley Lalonde, one of his team’s biggest off-season recruits, back in January of 2017.

Lalonde was officially announced as a recruit in late April 2018.

“If you want to have a successful program, it starts with recruiting. It starts with bringing the right guys and the right attitudes into your program.” — Marc-André Élement

Though Shemie noted that this was on the longer side of things, that’s 15 months in which Lalonde got to know the team he’s going to be playing for, learned about his coaches, and got comfortable with the people that will be around him next season.

“When you build relationships with guys, it makes it easier to be comfortable with them. It just made the process of choosing Concordia a lot easier,” said Lalonde.

The Stingers’ new defenceman noted that getting to know the coaching staff and the kind of hockey they want to coach was a big part of his decision. He knew that he would be playing a style of hockey that he fit right into, something that makes transitioning into a new league much easier.

Comments like Lalonde’s make it clear why Shemie likes to have coaches very involved in the process early on.

“It’s very important to the player that the coach really shows that he cares and that he’s willing to take the time out of his busy schedule,” said Shemie. “There’s a lot of things players look for when picking a program. One is that they want to feel wanted, they want to feel like ‘they really want me to come.’”

The sports aspect of recruiting is only one side of the coin. The word student is still half of the term student-athlete. Players need to want to come into the right academic setting and must meet the proper academic requirements.

Élement places a particular emphasis on academics for his players while recruiting, as well as once they’ve made the team.

“We can be a school where players graduate with a degree and then go play pro. That’s what we want,” said the coach, stressing the importance of balancing the two.

Academics may be the main off-ice barrier for local recruits, but for players coming from a different province or country, the idea of playing in a new city and culture can be daunting.

Even when teams manage bring in players from out of province, it means a lot more ground work for team officials. Western-born hockey players like Zachary Zorn and Colin Grannary , who need to find apartments in a city they don’t know, present plenty of paperwork and mean some extra hours for their coaches.

They also offer a level of skill that can pay dividends for a team willing to put in the work.

Grannary in particular demonstrates an element of recruitment that makes it harder to bring students to the Canadian universities. The Delta, British Columbia native played his junior hockey in B.C. but spent the last two years at the Division One University of Nebraska-Omaha in the United States.

Every program sees potential players lured to either the United States or, sometimes, professional offers. Dreams of full-ride scholarships in top American schools or a paycheck overseas are often too tempting to pass up for Canadian players, and coaches are well aware of it.

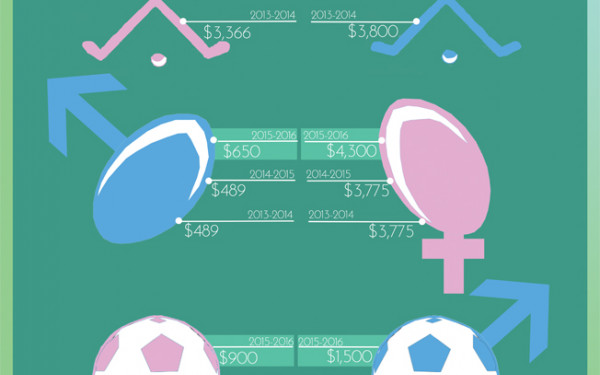

“The reality in Canada, except for a few exceptions, [is that it’s] not like in the U.S. where you’re throwing full scholarships at students,” said Sanchez of his experience competing with American schools with a high powered budgets.

Despite this, several Stingers teams have brought over players from American colleges in recent years. Grannary is joined by teammate Dylan McCrory who played for Bemidji State, a Division One NCAA school.

Stingers football has brought over back-to-back American quarterbacks in former league MVP Trenton Miller (University of South Florida/Mars Hill University) and current starter Adam Vance (Golden West College).

Professional offers have presented the Stingers with more trouble lately.

The men’s hockey team recently saw top prospects Jeffrey Truchon-Viel and Phélix Martineau sign American Hockey League contracts despite previouslysigned letters of intent with the team.

“We know that with some players we’re the plan B. They’re borderline playing pro,” said Élement, noting that while those players hadn’t joined the team, the fact that top junior players chose to sign with the Stingers is a bright spot for him in terms of attracting players.

The team still has the university league rights to both players.

From scouting to pitching, dealing with pro offers to working out academics, recruiting is months of work before a single pass is thrown, puck is dropped or goal is scored. It’s what crafts every team that will represent Concordia this season. Once the seasons begin, fans will see what that means.

4_600_375_90_s_c1.jpg)

_600_375_90_s_c1.jpg)