Montreal-based Naghmeh Sharifi explores the complexities of the human condition in latest exhibit

‘To Live As An Organ Within Oneself’ invites visitors to examine how the human form adapts

For multidisciplinary artist Naghmeh Sharifi, art has been a resourceful way to evoke feelings of nostalgia and memory; a feeling all too familiar to most of us as of late. Her latest display at the Verdun Cultural Centre is one to behold, and is currently welcoming visitors until June 27.

With vaccine rollouts now underway, and an ease in provincial restrictions, Quebecers are anxiously waiting to resume back to a life reminiscent of pre-COVID normalcy. Despite setbacks in past months, Montreal’s arts scene has continued to grow and showcase its talent through various forms of publicized displays.

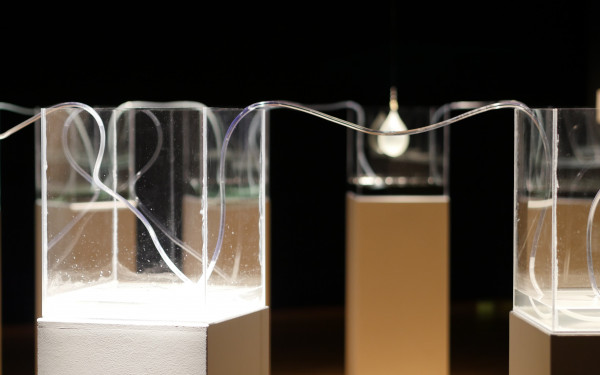

Titled To Live As An Organ Within Oneself, Sharifi’s exhibit addresses themes of transient identities as well as the psychology of the human body both internally and externally. According to Sharifi, her work in this series investigates how different social, cultural and geopolitical factors are able to leave us susceptible to change, specifically in terms of the ways our body language reacts to different settings.

“[The exhibit] offers viewers the chance to examine the ways in which people position themselves and interact with each other in different contexts,” said Sharifi. To her, the display aims to remind visitors of the impact that divergent cultural milieus have on both our psyche and the way it in turn affects bodily behaviours and overall corporal existence.

In order to properly relay her message to viewers, Sharifi drew all subjects depicted in her pieces. Thus, she was able to conceive a collection of drawings and sculptural elements that interpret the human body as a collection of complex geopolitical variables that shape each one of us.

Sharifi’s inspiration behind the pieces came from two artist residencies in Macedonia that she took part in a few years prior. Both residencies were inspired by the Roma population living in the Shutka neighbourhood of Skopje, Macedonia.

The Roma are known as a stateless and nomadic population in Europe. However, as Sharifi highlights, nomadic populations are constantly settling and relocating. Thus, their lack of legal status often adds to their precarious economic situation; a result often caused by lack of equal work opportunities.

While addressing the question of nationality in her encounters with the Roma population, participants overwhelmingly agreed that they either did not know their nationality, or did not identify with a particular nationality.

“That became the departure point of this series because I became interested in a sense of identity that was void of having a specific land or geography associated with it,” said Sharifi.

While To Live As An Organ Within Oneself does not singularly represent the Roma people, many of the images in the series are reflective of the artist’s Iranian background and personal life. In doing so, Sharifi’s work is mindful of the sensitivities of cross-cultural representations in art, especially as an Iranian-Canadian based in a multicultural space like Montreal.

“Both Iran and Canada are very much defined by national identity, especially Iran,” said Sharifi. “I was fascinated by transient identities that aren’t necessarily tethered to a specific land, but that exist either on their own, or in relation to each other.”

“Fundamentally, I [wanted to explore] the existence of people versus a nation, and how collective identities can be born from that,” she added.

“Fundamentally, I [wanted to explore] the existence of people versus a nation, and how collective identities can be born from that.” — Naghmeh Sharifi

Katrine Brink Claassens is an artist who has previously worked with Sharifi. She interpreted the exhibit as a universal depiction of marginalized communities that are often socially “othered.”

“Montreal is a city that holds many marginalized groups—immigrants, people experiencing homelessness, those marginalized in our systems due to their race, age and so many other things,” she said. “This is an exhibition that could speak to those people who are neglected, ignored and persecuted.”

Another particularity that is striking in this series of work can be seen in some of the common traits that many pieces share throughout the exhibit. From the choice of colours, to the coarseness of drawing papers, Sharifi did not hold back while attempting to explore different artistic mediums.

“I started off with black and white ink while in transit during my residency, and I couldn’t take my oil paints with me,” she said. Since oil paint takes longer to dry, and is not as transportable, Sharifi chose to stick to the basics.

“I just took the black from my watercolour,” she said. “I didn’t even have ink and just used paper. But those materials were light to carry around, and helped me to do quick interpretations and drawings while travelling.”

Sharifi soon realized how lack of colour was helping her center the subjects of her paintings and drawings. While completing silhouettes of her black and white depictions, she decided to make simplicity the cornerstone of her work for this series.

“At times when I did not have access to black ink during my residency, I switched to blue ink,” Sharifi said. “I really liked the monochromatic aspect that blue offered.” In turn, alternating between both colours allowed her to not only push the boundaries of the former, but to also add elements of nuance to her work that are reminiscent of nostalgia, distance and remoteness.

Similarly, her work is projected onto different types of paper that are not necessarily made of the same textures. This is because Sharifi only worked with paper she had access to during her travels, which allowed her to experiment with different fonts atop different surfaces.

Art historian and curator Elisabeth Otto has previously worked with Sharifi, and has witnessed her detailed and meticulous creative process first-hand.

“Naghmeh’s mastering of ink drawing—or better—the dance of ink and water on paper, is impressive,” said Otto. “She is generous with the medium, and at the same time, she knows exactly what effect she wants to create for the onlooker.”

According to Otto, one of the trademarks of Sharifi’s work is in its ability to be universally interpreted by viewers.

“Even if her images might be inspired by a specific encounter, they are universal in their humanity and timeless in their subject—the human condition,” Otto added. “They are never simplified, but always keep their individual complexities.”

Sharifi encourages Montrealers to embrace opportunities to visit exhibitions while maintaining COVID-19 safety protocols, and to benefit from the fact that many are free of charge.

To Live As An Organ Within Oneself will remain on display at the Verdun Cultural Centre until June 27. Moving forward, the series will be relocating to the Rosemont and Hochelaga neighbourhoods in the eastern sectors of Montreal closer to the fall.