Is the STM Selling Out?

Cash-Grab Threatens Beloved City Institution

Last week, the deadline passed for corporate sponsors to tender their company’s bid to plaster Montreal’s Metro lines with logos, leaving many Montrealers wondering which billionaires have bought their way into our daily commute.

The $155 million deal with the Société de transport de Montréal would see companies, who are required to have “sustainable development plans,” sign a decade-long contract, granting them exclusive rights to the Metro lines and its accompanying iconic symbolism.

The companies would also gain control over the visual landscape of a million riders who use the public service every single day.

In the 14-page call for submission proposal booklet, the STM boasted to potential bidders that the Metro “is a fundamental part of Montrealers’ lives and self-image” and is North America’s best and most productive transit system.

But beyond working well, our Metro has style and spirit. Inaugurated to show off a new, liberated Quebec for Expo 67 and distinguished worldwide for its art and architecture, our Metro stations have rich, individual histories and character—which is about to be saturated even further by brands and adverts.

If it is true that the Metro is a fundamental part of our lives and image, why are we selling out like this? Since when has our city’s self-image become so corporate?

Other world-renowned transit systems—like the metro in Paris, New York City Subway or the Tube in London—don’t seem to be resorting to the same cash-grab efforts to keep the trains rolling, so why are we?

At the base of this debate is the reality of how obnoxious our Metro will inevitably look as a result of this shortsighted plan. Very soon, the platforms, directional and outdoor signage, booths, buildings and maps are going to be dominated by Bank of Montreal and their ilk instead of, you know, directions guiding us from A to B.

Very soon, these “sustainable” brands will have total sway over our visual space and patrons will be at their mercy for a measly $15.5 million a year. (Editor’s Note: The use of the word “measly” is only relative to the STM’s current $1.2 billion annual operating budget and the projected $1.1 billion in additional investments they’ll make by 2020.)

But beyond the bottom line, what is the true function of the Metro system, really? What is the principle of this iconic map with four coloured lines? Its stated purpose is not to have you look at it and consider banking with the BMO, but to provide a vital municipal public service—to provide reliable and environmentally sensible transit options. Where and why did the STM decide to dive off the advertising deep end?

Proponents of the plan argue that advertising is already a huge part of our daily visual intake and to just quit whining and get with the fiscal times, but I ask them: why is advertising everywhere?

It’s because we keep permitting it to be put everywhere.

Perhaps it was an exaggeration when transit users’ group Transport 2000 asked “are we ready to sell our souls?” in The Gazette last week, but why are we continuing to excessively brand something that’s classic and characteristic all on its own? And at what cost are we doing this, really? What is the value of the real stories—and the cultural capital—of the Montreal Metro as it is?

When it comes to commercialization of public space, where do you draw the line?

-Laura Beeston

Corporatizing Something Corporate Isn’t Evil

Last week, le Societé de Transport Montréal announced that they are considering an advertising campaign proposed by the Bank of Montreal that could bring in $155 million over 10 years. If the STM accepts, BMO’s logo could be posted basically everywhere: on the iconic Metro symbol, directional display of the lead Metro car, collector booths, system maps, pamphlets, brochures, the STM’s website, arrows on the Metro floor, on busses and more.

This potential extra cash comes at a perfect time, just as 18 out of 20 of the city’s appointed highest earners gave themselves a raise—and most of them work for the STM. On top of that, 32 out of the 41 top earners at the STM received raises in 2010.

Projet Montréal told The Gazette that the average city employee’s raise was two per cent, whereas many top-earning STM employees received almost 13 per cent raises and one even received a 31 per cent raise.

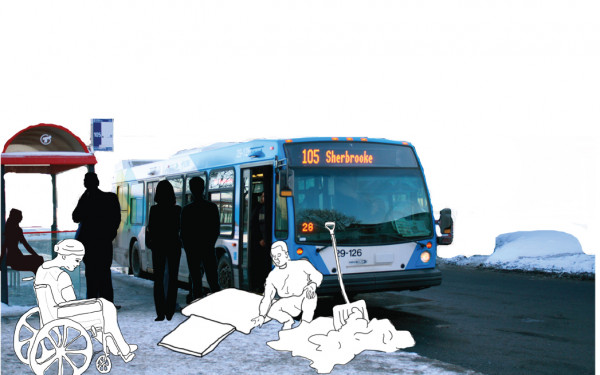

It also doesn’t look like transit fare prices are getting any more stable. For the past two years, the STM has been raising tariffs in order to cover new investment costs. If this keeps up, low-income Montrealers will be forced to trudge through the fierce Montreal winters without having the option of a warm commute.

So who’s going to pay for the $257,653 worth of last year’s raises, a whole fleet of new STM trains—whose cost is around $4 billion—and the existing costs of a new OPUS card system? It’s definitely not the advertising campaigns currently being housed by the STM. Montreal’s transportation system currently only brings in about $17 million in revenue from the ads in Metros, on buses and rent from the stores on STM turf.

If the STM accepts BMO’s offer, $15.5 million per year will be in the public-transport company’s hands, almost doubling its advertising revenue. The STM can’t rely on government funding and fares alone to raise money so they need to be open to different streams of income, or else the end-user will be negatively impacted. Government aid comes from taxpayers and so do the fares. It’s time to look at different ways to lessen the impact that debt can have.

Projet Montréal city councillor Alex Norris lamented to The Gazette that “plastering ever more of our public space with corporate logos and corporate names is not the most enlightened way of generating financing for public transit.” Well, as of right now, no one has put out a viable solution to cover costs other than corporate sponsorship.

Besides, if Norris has ever walked through the Metro, he’d find out that commuting via Metro and bus is like walking through a 3D GQ magazine. The walls are covered in messages that urge people to buy this and that. At Berri-UQAM station, a massive iPad advertisement protrudes through the comfort level of any sort of anti-corporate crusader.

My one concern is that I think the STM is selling itself short. Why haven’t they asked if anyone else was interested’in the ad real estate that BMO’s ready to drop nine figures on? If BMO takes the monopoly, it might scare away other companies that would want to advertise there—especially other banks. How are they going to raise roughly $10 million more in ad revenue to reach their goal if all of the ad space is already taken up to reach their $40 million goal in 2015?

Either way, I see no evil in putting up more ads when most of the underground scenery is made up of ads already. It’s time the STM figured out how to pay off their bills without forcing Montrealers to do so too by jacking up fare prices. If BMO’s offer will take the strain off of citizens, then I say go for it.

-Clay Hemmerich

This article originally appeared in Volume 31, Issue 23, published February 15, 2011.

__900_560_90.jpg)