Image+Nation returns for in-person and online programming

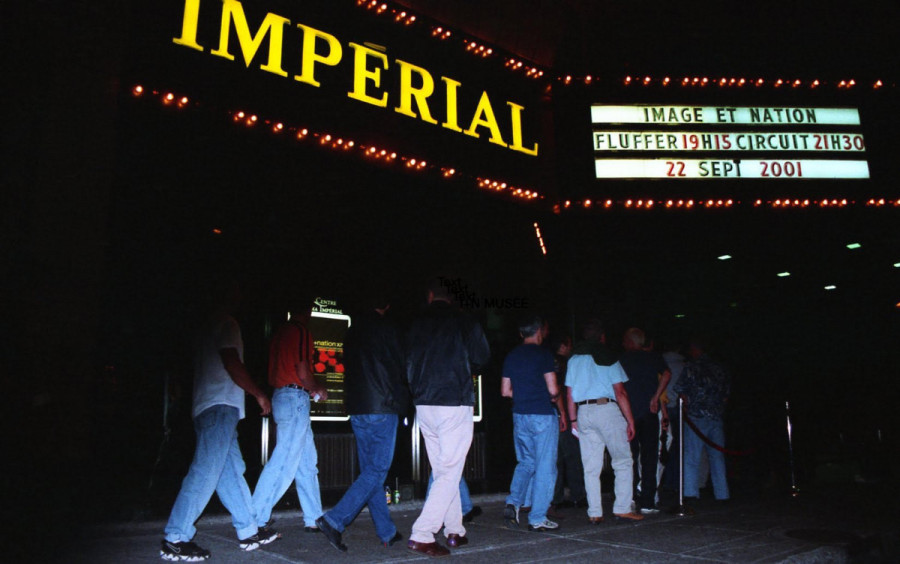

Canada’s oldest queer film festival celebrates its 34th edition

Image+Nation, Montreal’s free annual 10-day queer film festival, started Nov. 18 and will screen over 100 films from around the world. For the first time in its 34 years of existence, it will have both in-person and online components.

Kat Setzer, Image+Nation’s programming director, said the festival was started by artists and activists who wanted to give the queer community the media representation they deserved.

“It was started [in the] late ‘80s, a very different time [from today], by filmmakers, artists, and academics in Montreal—many of which, I believe, went to Concordia University,” Setzer said. “It was, in many ways, a political act [that was part of] a larger queer festival landscape.”

They added that queer festivals started coming into existence all across North America around the same time, in response to the emergence of the queer rights movements and the demand for queer visibility. Simultaneously, the invention of the video camera made filmmaking a lot more accessible to the general public.

Video artists who couldn’t screen their work anywhere else came together to form Canada’s first LGBTQA+ film festival—then called Image+Nation gai et lesbienne.

“It started off as one or two days of screenings, almost putting up a white sheet on a wall and projecting [on it]. It was a real grassroots movement and then it slowly grew,” Setzer said.

“The fact the festival has survived this long, and through the pandemic is nothing short of a miracle.” — Richard Burnett

“The history of the festival is really interesting. It very much is also the history of queer cinema,” they said.

The content this festival produces, as well as the diversity of identities represented, have evolved parallel to a queer cinema movement, the Concordia alum said. The term “new queer cinema” was coined in the mid-’90s to describe this movement.

According to Setzer, the content of the festival also varies in line with the socio-political landscape. When the AIDS epidemic broke out, documentaries talking about AIDS activism were screened; when trans and non-binary identities became more accepted, documentaries covering transitioning were featured.

For several years, Image+Nation was about coming-out stories, the programming director said. “Those beginnings of telling queer stories have evolved to include different aspects of people’s lives. […] Your queerness is just one aspect of your identity.”

These coming-out stories eventually became more nuanced, pluralistic representations of queer identities, said Setzer.

“It’s really been such a privilege to be a part of a festival and to witness this really exciting development of a cinematic practice,” they said.

Jules de Ninerville, who will be screening his short film “Parle-Moi” this year, discovered Image+Nation in the very beginnings of the festival. The festival then featured a student film de Ninerville made as he was graduating from Concordia. That is also when he met Setzer, who was already very involved in the festival.

Read more: Concordia’s new Queer Film Club hosts its first event

In 2015, when he released his first film, “Twitch,” he started working with Queerment Québec, a specific program within Image+Nation focusing on Quebecois cultural perspectives. “Twitch” went on to win that year’s public award for best short film.

“Since then, both Kat and Charlie [Boudreau, the festival’s executive director] have also become good friends of mine, so it’s been quite a rewarding experience throughout,” said de Ninerville.

Queerment Québec’s annual program began in 2000, and the filmmaker has been a regular attendee over the years.

“For me, Queerment Québec is a great way to have a larger umbrella in terms of embracing a community of diversity,” he said.

For de Ninerville, being queer means being outside of the norm and includes people who are in the process of finding their sense of identity and community within the LGBTQA+ community.

De Ninerville is very enthusiastic about screening his film “Parle-Moi” this year, as it has already appeared in 20 festivals so far and won three awards.

“It’s really about the sentiment of being on the fringe and seeking [a] sense of fraternity or closeness with someone else,” he said.

The short film has no dialogue, and relies on circus arts to communicate the sentiment of not fitting in.

“I felt circus arts was the perfect way to strike a little bit of humour and really exaggerate the point and hopefully be entertaining and get a larger audience,” the filmmaker said.

Richard Burnett, a renowned Montreal LGBTQA+ journalist who has been attending Image+Nation for many years, said that it is crucial for queer folks to have accurate representation in cinema. For the longest time, he said, the film industry has portrayed queer individuals as being predators and serial killers. Famous examples can be found within the ‘80s American slasher film genre, including High Tension and Psycho. Although the latter wasn’t an explicit portrayal of a trans woman, Psycho led to the creation of a new subgenre of horror rooted in transphobia.

Image+Nation, on the other hand, has been providing real representation to the queer community since 1987.

“The fact the festival has survived this long, and through the pandemic is nothing short of a miracle,” Burnett said.

He added that having online events this year is beneficial in the sense that it allows the festival to be accessible to people who live outside of the city as well as to people who are still weary of attending in-person events. However, he is excited to be able to sit in a theatre again.

“Being in the same room as other festival goers helps build community and identity,” said Burnett. “After all these years, there is still power in gathering together in a dark cinema.”