“Hyper Real”-Life Experiences of What It Means to be Black in Montreal

Challenging the Politicization of Black Bodies and Experiences Through Art Exhibited at the VAV

“As a Black artist, our art and existence always has to be political, […] everything you do is as a ‘Black person,’ it’s never as [yourself],” said Grapes, a Montreal based artist in attendance of the vernissage for Hyper Real.

This article has been updated.

“White people get to be [themselves] but we get to be a box, a colour, a societal norm.”

But this exhibit expresses itself in ways that challenge that expectation.

“I like the rawness of every artist, how they try to capture [the individuality of a person],” continued Grapes.

Hyper Real: Black History Exhibition and Event Series is a conglomerate of art pieces that relate a story of Black identity.

In the Visual Arts Visuels’ current exhibit, nine artists are featured, who each express what it means to be themselves, or a form of themselves. Whether explicitly political or individualistic, the pieces at the VAV compliment and speak to each other, documenting a cohesive account of Black experience.

Having a Black History Month exhibition in November was deliberate, explained Susan E. Callender, the outreach coordinator at the VAV gallery and a curator of Hyper Real.

Having two exhibits featuring Black artists to celebrate Black History Month in one year allows for Black artists to have access to work outside of the month of February (in which they are severely overworked), explained Callender. This was a concern brought up at a discussion panel the VAV held last Black history month, which pushed the VAV to counteract this phenomena.

Callender hopes to “also kind of conceptually challenge the way that we live, the space that Black folks get, and that Black art gets, and [to ultimately challenge how] Black history gets to be talked about within our educational institution.”

Walking into the Hyper Real exhibition, the entire right hand wall displays Karl Obakeng “Oba” Ndebele’s work. Made up of a video piece and of three photographic series, Oba wanted to create Black art without any pain.

All nine artists spoke about the pieces they displayed, and Oba talked about how the expression and the representation of finding oneself in Oba’s series is an experience without suffering.

“[The exhibit] also addresses a huge need, […] and lets people know that, for sure, this is a space that is actually for you.”⎼ Susan E. Callender

Oba was telling how he doesn’t want his work to have pain in it, and that kind of resonated with me,” explained Grapes. “A lot of times, as a Black artist, there’s a lot of pain or [triggering themes] in [their art]. Oba’s piece was safe, in [an emotional] sense.”

Every piece in the space was remarkable, different and personal. “[The exhibit] also addresses a huge need,” said Callender, “[…] and lets people know that, for sure, this is a space that is actually for you.”

Callender also explained that when one doesn’t see themselves represented in art or in a space, one tends to believe that they don’t belong there, and this definitely should not be the case.

“Because of the [artist] call out [for this Black History Month exhibit], I think Black identity was a huge theme centred in those works,” continued Callender. As were “raw, or very exposed or vulnerable approaches to that subject.”

RELATED- Elizabeth Eugene Debuts Multimedia Piece “Allow Me To…” at the VAV

- Hyperrealist Artist Daniel Itiose Exhibits Expressive Paintings at the VAV

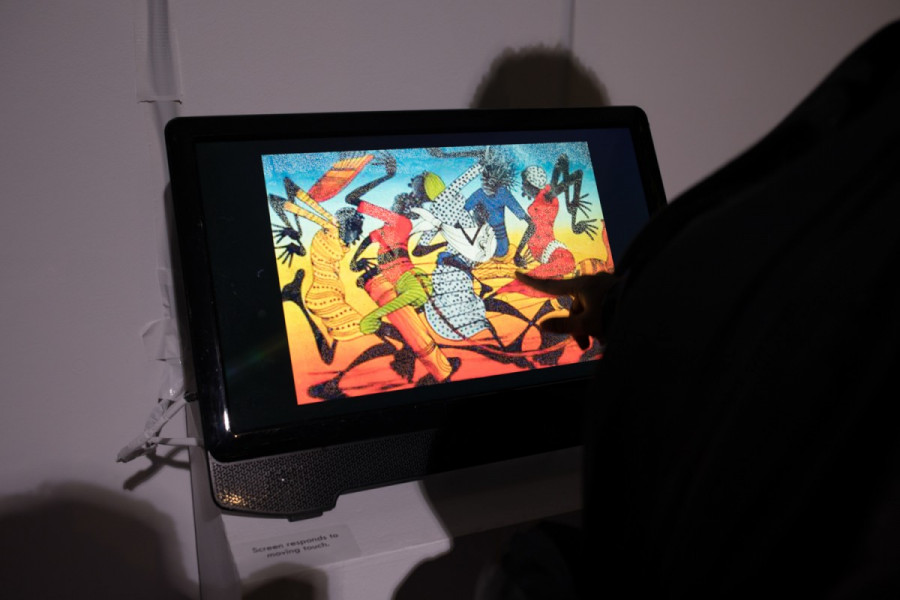

In the back right corner, behind a curtain, there are two digital pieces from two different artists that are placed side by side, which exemplify this.

To the left is Naïka Deluy-Garwood’s video installation of her shaving her head, called “People would kill for hair like yours,” and to the right is Elizabeth Eugene’s “Allow me to…” which is a multimedia piece expressing the experience of the “fat Black woman.”

“I wanted [the piece] to be big and overwhelming, so you have that sense of embodiment, and to be swallowed in the space,” explained Eugene about her piece.

Eugene also expressed contentment with having a corner to herself for her piece. “And when there’s not all of this noise, it’s really quiet and poetic, and you are […] really entranced with that. You’re […] in that bubble, and you’re allowed to talk and to think about that subject.”

“[Naïka’s piece] is similar because she tried to […] take back her body, [with] her hair, and with [my] piece I’m trying to take back my body from what everyone told me all my life. I feel like they connect really well, it’s a different part of female bodies, it’s a different retribution, but it’s similar in a way.”

Callender explained that the name of the exhibit Hyper Real stemmed from the fact that there was a hyperrealist artist, Daniel Itiose, featured in the curation.

Itiose has two of his hyper realistic paintings of the same subject facing one another on two parallel walls, which was the curators’ choice. “I like the mirror effect, because you have to back up from one to look at the other, and the further back you get to the other one, the closer you get to the other […] it abstracts itself,” commented Itiose. “I like that push and pull [result].”

The exhibit featured more art that represented “real and tangible things, like, experiences that people are actually living, or people have actually lived,” said Callender. “All of the art […] has the content […] that reaches to a human place in people, and I think that’s what the ‘real’-ness is about signalling.”

To check out more of the art exhibited at Hyper Real, go to the VAV gallery on 1395 René-Lévesque Blvd W., between 9 a.m. and 9 p.m., Monday to Friday until Nov. 30.

A previous version of this article stated that Naïka Deluy-Garwood’s piece was titled “People would kill for that hair”. In fact, the title is “People would kill for hair like yours”. The Link regrets the error.