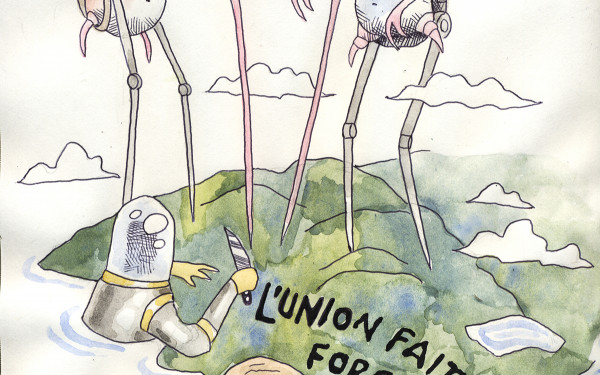

“Haiti’s New Dictatorship”

York Professor Launches New Book Detailing “UN Occupation” of Haiti

Haiti’s been on our collective radar for years now—first the coup d’état, followed by the 2010 earthquake, the cholera epidemic and now Hurricane Sandy.

Since 2004, the United Nation’s Stabilization Mission in Haiti, MINUSTAH, has been on site.

In an event sponsored by Canada Haiti Action Network and Concordia’s 2110 Centre for Gender Advocacy, York University Associate Professor Justin Podur will be launching his book, Haiti’s New Dictatorship: The Coup, the Earthquake, and the UN Occupation, and discussing some of the issues he addresses, specifically, Canada’s involvement.

“Haiti is one of the worst examples of Canada’s international behaviour,” said Podur, whose interest in Haiti stems from his study of Canadian foreign policy. Podur writes about how countries are on Haitian land without its people’s consent, and that corruption and inefficiency has lead to sparse improvement of the country’s conditions.

Many countries including the United States, France, Brazil and Canada are currently occupying Haiti under the UN banner. In 2004, Haitian President Jean-Bertrand Aristide was forced into exile, and has since blamed the international community for staging the coup against him.

President Aristide’s election in 2000 was believed to be fraudulent and international aid to the country was cut off until his ousting in 2004.

Although the UN Security Council’s 2004 resolution states that it is “affirming its strong commitment to the sovereignty, independence, territorial integrity and unity of Haiti,” Podur says that they are actually denying Haitians’ right to sovereignty.

Podur has visited Haiti twice, and his research has shown that there are certain similarities between the UN occupation and a dictatorship.

The MINUSTAH mission in Haiti is renewed every year despite the population’s disapproval. To illustrate the lack of accountability, Podur uses the examples of widely criticized UN anti-gang operations in Cité Soleil, the capital’s biggest slum, and the cholera epidemic brought to the island by UN soldiers.

“It’s a common belief that we don’t want to donate to support corrupt governments, but that’s true in Haiti too,” said Podur. “International regimes that govern Haiti are the same.” He says that donations to Haiti rarely ever get to Haitians.

Podur’s objective is to raise awareness about the issues at play in the Haitian political arena. While it’s not abnormal for the international community countries to infringe on a country’s sovereignty in exceptional circumstances, in Haiti it has lasted eight years.

“You have to ask how does the international community perform compared to the government they overthrew,” said Podur. “In Haiti, the international community is worse in every domain than the government it overthrew.”

According to Podur, participating countries have agendas other than helping the Haitian people.

After Haiti’s independence in 1804, the country was forced to pay a huge compensation fine to France who had lost so many slaves. Before the coup, President Aristide had been demanding reimbursement from France, and Podur says France didn’t want any more mention of that controversial transaction.

As for Canada, Podur says this was the Canadians’ chance to redeem themselves in the eyes of the U.S., with whom they had had strained relations because of their opposing views on the Iraq war.

“The only people who have Haitians’ best interests at heart are Haitians,” says Podur. “If sovereignty is good enough for Canada, it’s good enough for Haiti.”

Podur says there are many Canadians looking to contribute to the Haitian cause but they can’t see where their money is actually going.

“It’s important to give aid in a spirit of solidarity, with criteria that it should bolster sovereignty,” says Podur.

He recommends donating to grassroots organizations that work directly with the Haitian population.

Podur’s talk is taking place at 7 p.m. on Nov. 13 at in Room 767 of the Hall Building, 1455 De Maisonneuve Blvd. W.

_900_596_90.jpg)