Canada Helped Overthrow Haitian Democracy

A Peoples’ History of Canada Column

Wednesday marks the 13th anniversary of a coup d’état in Haiti.

On Feb. 29, 2004—it was a leap year—a Canadian-led assault on Haitian democracy forcibly removed the social democrat President Jean-Bertrand Aristide.

Current Montreal Mayor Denis Coderre—who was the minister to La Francophonie and Prime Minister Paul Martin’s special advisor to Haiti—said on Feb. 20, 2004, “It is clear that we don’t want Aristide’s head; we believe that Aristide should stay,”

Nine days later, Canadian Special Forces landed in Haiti—taking over Port-au-Prince airport, securing it as a beachhead for the deployment of US Marines and other international soldiers. The invasion of Haiti had begun, and Canada played a key role in it.

Aristide said he was kidnapped by US Navy SEALs, on Feb. 29—taken at gunpoint on a flight to Central African Republic and threatened that “a lot of people would die” if he didn’t resign. The US State Department denied these allegations, saying that Aristide resigned on his own accord. The former president then lived in exile in South Africa until his return to Haiti in 2011.

On Feb. 29, 2004, President George W. Bush said, “President Aristide resigned. He has left his country. The constitution of Haiti is working—there is an interim president in place. […] As for the constitution in place, I have ordered the deployment of Marines as the leading element of an interim international force to help bring order and stability to Haiti.”

The occupying forces, including Canada, installed an interim government. Gérard Latortue took over soon after as Prime Minister.

Jean-Bertrand Aristide was first elected president of Haiti in 1991, with a 67.5 per cent majority in the country’s first internationally recognized legitimate election. Eight months later he was taken from power after a CIA backed military coup.

In 1994, after a crippling UN embargo which left the country in ruins, Aristide was reinstated to power with the help of US military forces—but only after agreeing to work with the Clinton administration to “substantially transform the nature of the Haitian state.” Basically, Aristide was being asked to end his social-democratic reforms and accept privatization and austerity measures.

Aristide was certainly no perfect saint, with multiple reports of uninvestigated and possibly politically motivated assassinations. While in charge, however, the human rights situation in the country improved considerably. The literacy rate increased from around 30 per cent to 55 per cent. As well, he doubled the minimum wage, and instituted the rule of law—with courts operating in Creole instead of French. The malnutrition rate dropped from 63 per cent to 51 per cent, and he created a medicine-training program with the help of Cuba. He even disbanded the Haitian army, a repressive institution that had only ever fought its own people.

Denis Paradis, then Canada’s Secretary of State for the Francophonie, Latin America, and Africa held a secret meeting in 2003 called the “Ottawa Initiative on Haiti.” The meeting, held in Lake Meech with representatives from the US, France, El Salvador, the European Union, and the Organization of American States, discussed placing Haiti under the “tutelage” of the UN, possible military intervention, and the removal of Aristide from power. No Haitian representative was present at the meeting.

According to Yves Engler, co-author of the book Canada in Haiti: Waging War on the Poor Majority, the 2000 elections in Haiti were widely contested by opposition parties aligned with the business class and petite bourgeoisie of Port-au-Prince. They alleged that the legislature elections were rigged and that the rules were not respected. Opposition partisans organized a boycott of the presidential elections, giving Aristide a victory with more than 92 per cent of the vote. This was only a scheme to delegitimize the elections by the Haitian upper classes to destabilise the government in place.

Aristide’s social democratic policies threatened the Haitian business class and western multinationals. It seems clear that the coup was motivated not by worry for the poor Haitian population but simply by economic interests.

And the economic interests of Canadian corporations are doing pretty well, since the coup. Gildan is a Montreal based company with annual revenue of about $2 billion. It operates its factories in Haiti. Gildan doesn’t pay their workers minimum wage in Haiti. It systematically steals about half the wages, forcing their employees into debt, to live in slums and to only eat one meal a day. When the workers try to unionize, they get fired. Nine per cent of the company’s shares are owned by the Caisse de Dépôt et de Placement—a Québec government investment fund, our retirement fund.

There’s also gold, copper and bauxite on the island—the gold reserves alone are estimated to value $20 billion. Canadian corporations dominate the mining industry in Haiti, just like elsewhere in the Global South. Two of them—Ste-Genevieve Resources and Eurasian Minerals—resumed their operations shortly after the Latortue government was instated. Ste-Genevieve owns the prospecting rights for 10 per cent of the entire country, according to Yves Engler.

Steve Lachapelle—a board member of Ste-Genevieve—said to The Toronto Star that “with all the problems the country has had, they realize that they have to play the game with investors or things are going to keep getting worse.” With the horrific track record of Canadian mining corporations around the world, Haitians are unlikely to get their fair share when the extraction begins.

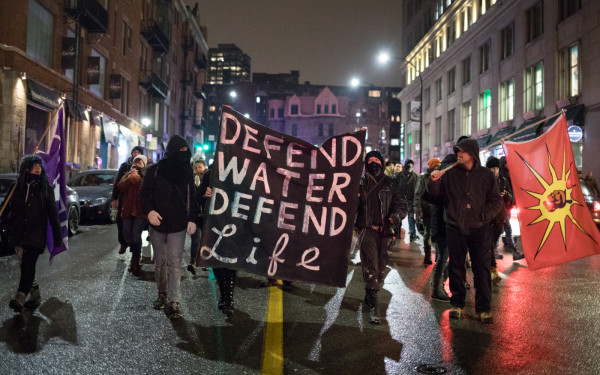

Since the UN peacekeeping force began occupying Haiti, they have been held responsible for many atrocities. From the cholera outbreak of 2010 that killed over 9,700 Haitians—which occurred after a Nepalese Blue Helmets camp dumped sewage water in rivers people drank and bathed from—to the multiple instances of massacres in the pro-Aristide slums like Cité-Soleil.

The death toll from the occupation has since well-surpassed 10,000 people. While Aristide’s administration wasn’t free of critique, the human rights situation has greatly deteriorated since western powers—including Canada—took over to protect our economic interests in the country.

In a diplomatic cable released by Wikileaks from 2008, the American embassy can be seen advocating to prolong the military occupation to prevent “resurgent populist and anti-market economy political forces.” In other words, the occupying forces are afraid of Haitian democracy.

There’s a proverb in creole: Konstitusyon se papye, babyonet se fe. A constitution is made of paper, but bayonets are made of steel.