Fine arts students find creative ways to adapt

How lack of access to studios and materials is affecting fine arts programs

Campus art studios are critical to the learning process of fine arts students.

Not only do they provide students with the necessary equipment to produce their work, but also a safe space to discuss, compare, and bounce ideas off each other. However, university art studios have been closed since the beginning of the pandemic, forcing art students to find alternatives.

Here’s how four university students adapted to the current situation and its challenges.

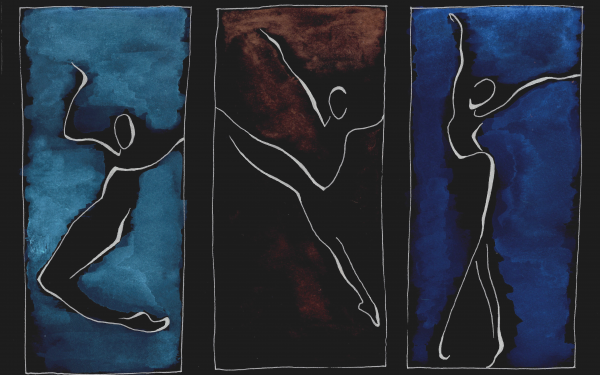

Sampson McFerrin

Second-year drawing and printing student Sampson McFerrin moved into his new apartment this year. Choosing his home was based on two specific criteria: having enough space for a studio and being close to his Stingers practices. Now, McFerrin and his roommate, two cross-country Stingers athletes, can study, easily commute to workouts, and freely draw.

“Overall, I just adapted to learn how to most effectively use the space that we have and also learn where certain stuff shouldn’t happen,” McFerrin said. “I avoid entirely bringing my computer on my bed. That would mess up not only my sleep schedule but my studying as well, which I can fortunately do in this apartment.”

Utilizing his space is not the only thing McFerrin forced himself to do. He also realizes that as an art student, most of his creativity comes from commuting, walking around the city and being out of his work and home environment.

“That’s when you see things you wouldn’t otherwise see,” he said. “Thankfully, I’m on the cross-country team and I have to go outside to run every day. But for people who aren’t as active everyday, maybe they only have to go outside for groceries or send a box or get packages.”

But one thing is certain for McFerrin, being in a fine arts program doesn’t require always being in front of a screen for schoolwork.

“I’m glad that I can look at a canvas and not at technology all day long!” he added.

Arthur Genest-Ouellet

First-year photography student Arthur Genest-Ouellet was not expecting to learn his art online when he enrolled at Concordia. Attracted to the hands-on nature of the program and studio access, he was hoping to learn how to develop film and learn from fellow artists.

“When I learned the news, I was sad because I knew it was going to change my entire year,” Genest-Ouellet said. “It’s disappointing because it’s a big part of this program.”

His biggest challenge was to adapt to his woodcarving and relief making class. Usually, he would have had access to carving tools and print machines. Now, he has adapted half of his desk strictly for his carving tools and the other half for his photography setup. Although it isn’t the same as working in a studio, he says it does the job since all assignments were modified to be done from home.

“A good aspect is that since classes are from home, you can go back and see what you’ve done which is good for retention of the information and studying, which isn’t the case in regular classes,” he said.

Although Genest-Ouellet is enjoying his first year in fine arts so far, he says he’s eager to isolate himself not at home but in the photography blackrooms—something he hopes will happen next fall semester.

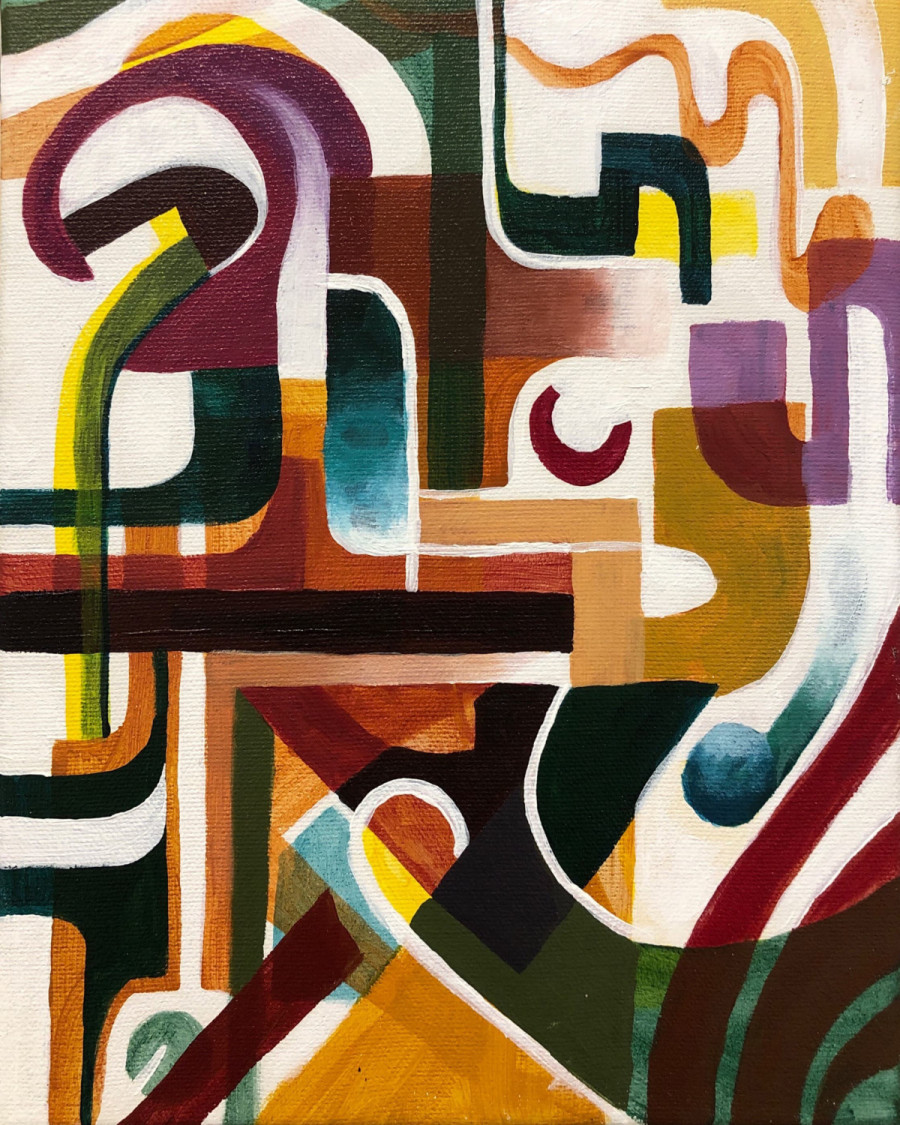

Damien Chabauty

After coming back from Los Angeles in late August, Damien Chabauty had a rough beginning of semester. While he would usually paint in the Mile-Ex studio he and seven of his friends rented, he had to confine himself at home for 14 days.

“I had a big rug in the corner of my room and I pushed the stuff so I wouldn’t dirty anything,” Chabauty said. “It was very limiting because you don’t do big gestures, you’re super careful, you’re always working on smaller things, and it impacts the technique depending on what you’re working on.”

Since September, he’s been producing in his studio which wasn’t affected by the new COVID-19 measures. “I’m just glad to be back in studio.”

Chabauty has been producing and selling his work professionally for three years now, but considering uncertainties due to the pandemic, he decided to slow down on professional work, to quit his job as a waiter, and focus on his studies.

“I also considered taking a year off, but instead I took more classes,” he said. “I don’t want to drag this on and on, and at some point I’d like to finish.”

So far, Chabauty has been getting used to the current situation, but is hoping to start working on new projects and experimenting with new techniques in the coming months.

Olivia Handfield

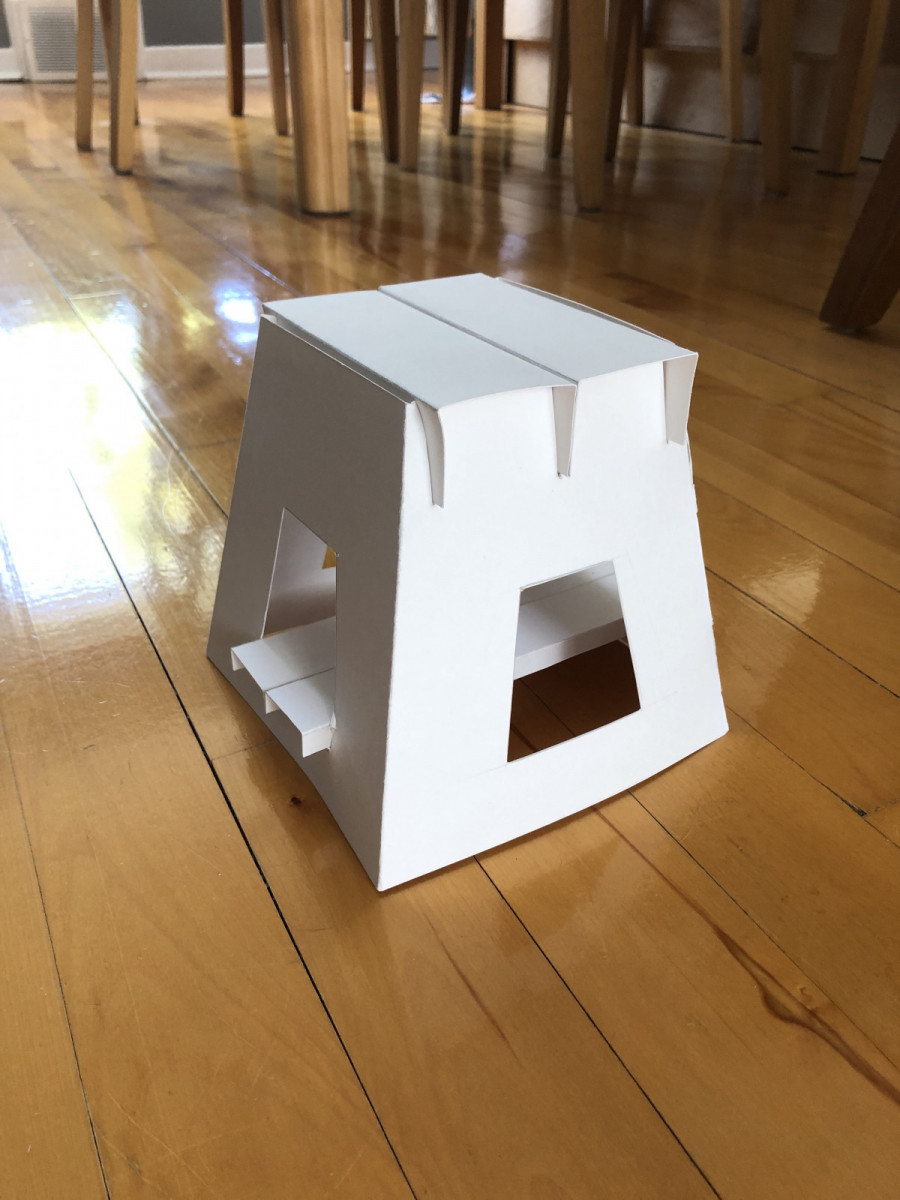

Industrial design mixes both hands-on building and designing on computers. Second-year Université de Montréal student Olivia Handfield faced many mishaps before getting on track with online classes.

“I had to invest in a new computer and a monitor because I didn’t have access to the ones at school, and for the projects we do, we can’t do them on regular 13-inch screens,” she said.

She also had to learn new software since some are exclusive to PC and others to Mac OS.

Another major issue is access to materials. There are three studios at UdeM: one for metal work, one for wood, and one for plastics. Now she can’t work with any of these materials since she doesn’t have access to the necessary machinery and has had to find alternatives.

“I’m very lucky because my dad works in the movie industry and he is a props master so I have access to a lot of material because of him,” Handfield said. “But for other people who don’t have access to other materials who were accessible at the coop, for them it must be a lot different from me because I can still figure out some things with my dad who has the creativity and ingenuity about materials and is always going to help me.”

As a very hands-on program, Handfield is somewhat disappointed in the industrial design program’s online transition. “We have to adapt with what we have at home like shoeboxes and cereal boxes,” she said. “At this point it’s more like crafting than industrial design.”

Although all four students are staying optimistic through the pandemic, they all feel they are missing out on an essential part of their art education: access to materials and studios.