Empowering Indigenous Women in Prison

How Incarcerated Women Use Art to Heal

Dr. Felice Yuen is soon to embark on a brand new project, one that will focus on the healing of Indigenous women in provincial incarceration through traditional art-based methods.

A professor in leisure sciences and applied human sciences at Concordia University, Yuen has long been involved in research with Indigenous women, and trying to understand and explore what healing means for them.

“For my PhD, I was working with Indigenous women in federal prison, and trying to understand how involvement and engagement in ceremony impacted their healing,” Yuen explained.

“My involvement with my PhD, these women, and the relationships I developed with [them] inspired me to continue this research when I was hired at Concordia.”

This upcoming project has been on Yuen’s mind for quite a while, especially in the last few years.

“People are seeing that we need change.

There’s an over-incarceration of Indigenous women everywhere, and Quebec is not an exception. We’ve got to do something about it.”

But in order to understand the purpose of this upcoming endeavour, it is important to take a look at the adventure that started it all: Journey Women.

Journey Women regrouped eight Indigenous women from Minwaashin Lodge, an Aboriginal support centre in Ottawa, back in 2010.

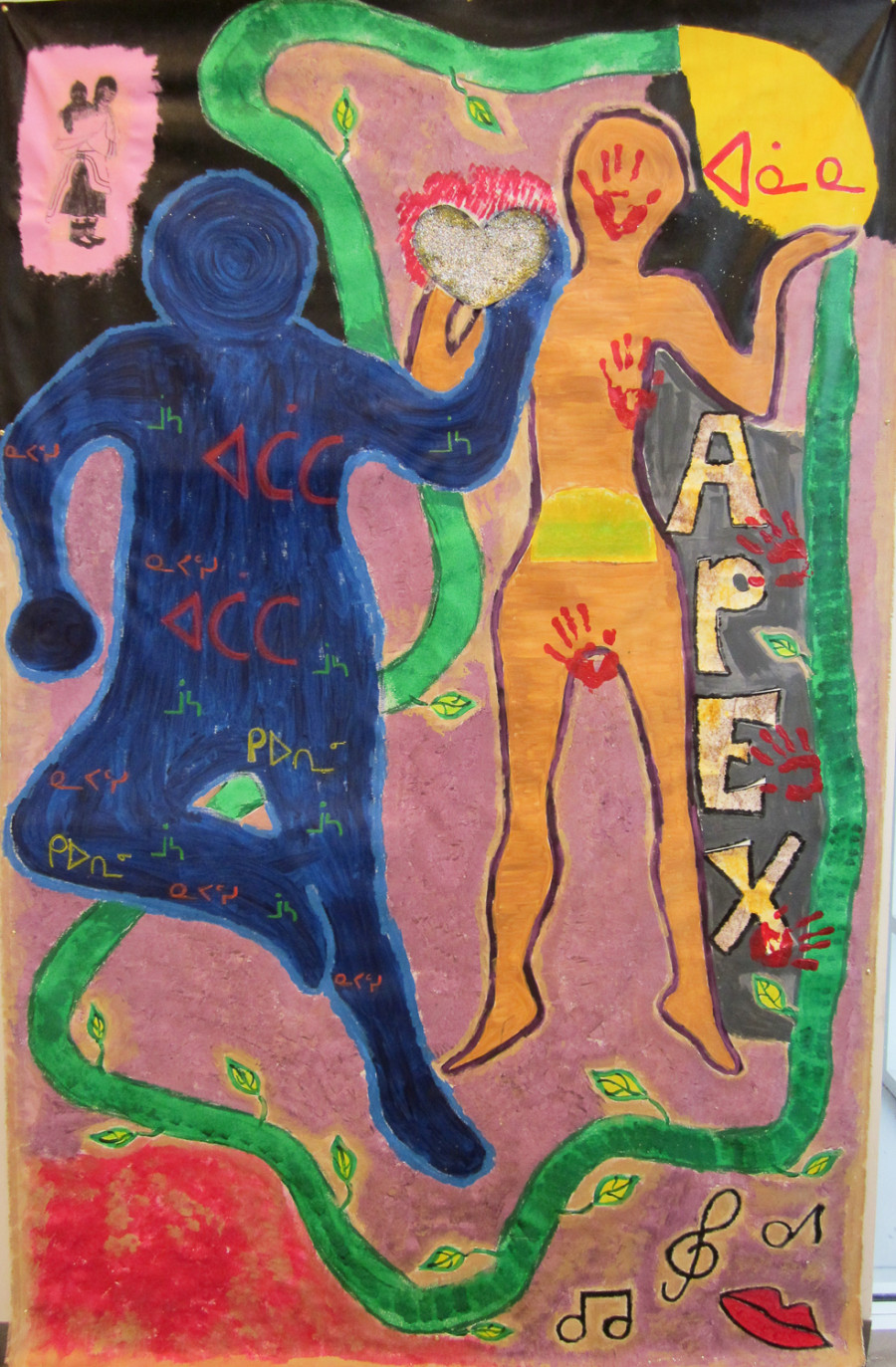

The project led the women—or artists—to explore their healing through ceremony, song and drumming, talking circles, and other techniques stemming from Indigenous cultures.

The knowledge gained through these processes would later help them create a body map that would serve them both as an emotional outlet—as part of their healing journey—and as a tool to illustrate their strength and resilience.

For the women at the Minwaashin Lodge, their experience of healing also gave them a desire to share their newly acquired knowledge, Yuen said.

“For them, it was like, ‘We have knowledge, and skills, and understanding, and a way of healing ourselves that we want to share with the world.’ So that’s [where] Journey Women came from,” said Yuen.

Journey Women is indeed about sharing—that is one of the main points Yuen insisted on, during the project and continuously long after.

“This project is still ongoing as things arise,” she said. “I would say that the publications, like the formal academic publications, are slowly wrapping up.”

But the project is much more than just academia—through the art created during the workshops, Journey Women still lives on, she highlighted.

“It’s making change in the world, it’s making a statement. It’s sharing important pieces of knowledge,” Yuen added.

The next step in Yuen’s own journey now resides in provincial prison, in particular, the Leclerc Institution in Laval.

Yuen will be leading a research project in the prison, tailored towards Indigenous women, and hopes to achieve the same healing outcomes as Journey Women.

Data revealed in June of this year by Statistics Canada show that across the country, Aboriginal adults are overrepresented in the correctional system, both in the federal system and across provincial establishments.

While representing only 4.1 per cent of the overall Canadian adult population, Aboriginal adults made up 28 per cent of inmates in provincial or territorial correctional services, all provinces and territories combined, and 27 per cent of inmates within the federal correctional system.

Ultimately Yuen said this upcoming research project could develop an understanding of the people in the judicial system.

“[The project] needs to consider things like cultural safety and decolonizing research, all these sorts of things,” said Yuen.

“It’s making change in the world, it’s making a statement. It’s sharing important pieces of knowledge.” — Dr. Felice Yuen

For this upcoming project, Yuen, as part of Concordia University’s staff, will be collaborating with the Elizabeth Fry Society of Quebec, as well as Wanda Gabriel, an assistant professor at McGill University’s School of Social Work and citizen of Kanehsatake Kanieke’ha:ke nation (near Oka).

Gabriel has been doing healing circles for close to 20 years, and is specialized in residential school survivors’ trauma.

“I’ve worked with survivors, with people who had been through [the judicial] system, had been out and [were] still dealing with trauma,” she said.

“I thought it would be great to provide support and tools while they’re inside [the prisons].”

For Gabriel, the purpose of this project is to help incarcerated Indigenous women overcome the cultural genocide forced upon their communities, often leading them to keep quiet about their trauma.

“When we’ve been through oppression, one of the ways to survive is to disconnect from our feelings,” Gabriel added. “If we can walk with these women to help them break [that pattern], so they can find their voice, then our project is a success.”

Aleksandra Zajko, managing advisor at the Elizabeth Fry Society, described the project as a way to better develop and adapt the judiciary system for Indigenous women.

The Elizabeth Fry Society specializes in offering services for incarcerated women both in federal and provincial services, but this is the first Indigenous-focused program the Quebec based branch of the Society has ever conducted.

While the project will focus on the healing of those incarcerated Indigenous women, the Elizabeth Fry Society hopes to take from the initiative new and better ways to help them navigate the system and adapt it to their needs, by looking at the personal and systemic obstacles they face.

“We really want to adapt our services,” Zajko insisted. “We not only act as a facilitator to this project for both researchers, [Yuen and Gabriel], but we also want to know what will come out of it in terms of recommendations, and what role we can play in acting them out.”

More importantly, though, this project—just like Journey Women before it—aims at shedding light on the situation of Indigenous women across the province, even across the country, through research.

“Normally, you just write. You write papers, and give presentations, and it’s within the academic world,” Dr. Yuen described. For her, however, the sharing of knowledge cannot be done through research alone, but mostly through the art created as part of it.

“It will live on for the rest of our lives; meaning every woman involved in Journey Women, […] and for myself.”

_600_375_90_s_c1.jpg)

2_600_375_90_s_c1.jpg)