Editorial: United Against the Charter

Though it took them a while to get it off the ground, the administration has done an excellent job of standing up for Concordia’s values.

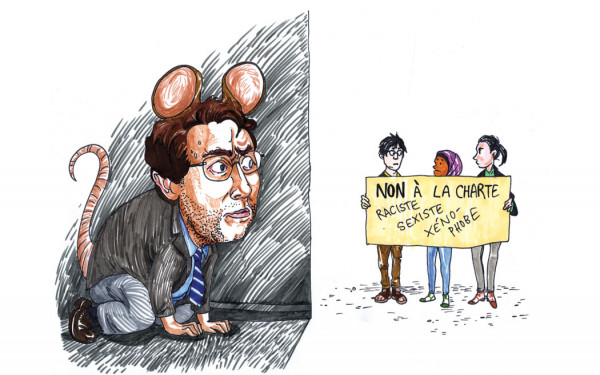

Provost and VP Academic Affairs Benoit-Antoine Bacon and VP Services Roger Côté represented our university at the National Assembly last Thursday, deftly handling the frequently obtuse, if polite, questions leveled at them by Bill 60’s author, Democratic Institutions Minister Bernard Drainville.

They were there to present Concordia’s stance against the Charter of Quebec Values, in the public hearings to take the pulse of Quebec society on an issue that has been subject to a consistently polarizing tone—even for Quebec.

Although Concordia could have come out with its official position sooner, their long deliberation process has made their argument nearly airtight. The administration says they received about 200 emails with an opinion on the proposed charter—with about 98 per cent rejecting the ban on so-called “ostentatious religious symbols,” according to Bacon.

Students, faculty, employees and various groups at Concordia have been vocal with their concerns about such a ban since plans for the charter were announced last fall. Concordia listened to those concerns, and Bacon and Côté communicated them to the government with poise and confidence.

Bacon seemed quietly intent on dispelling the myth of the angry, unreasonable student, an image that has unfortunately haunted the idea of student opposition in Quebec even before the 2012 strike. In keeping with this attitude, he and Côté repeatedly refused to play into labelling games, saying that they didn’t know how many students or staff bore so-called ostentatious religious symbols.

We don’t have any reason to keep such data. As the two told Drainville, it’s irrelevant—the university has never received any complaints over religious symbols on campus.

Concordia is a model for the peaceful functioning of a diverse community, spanning a wide variety of countries of origin, faith, generation and ideology—something that Drainville would have known had he bothered to show up to the planned charter debate last semester.

Bacon and Côté hammered home the point that “diversity is our strength,” and that we are not in the business of denying anyone an education who has the capacity for it. Concordia’s history is one of a diverse student body, and continues to be. That nearly half of Concordia students are the first in their family to go to university according to Bacon, and that our academic community has about 150 different countries of origin, attests to this fact.

Religious symbols are but one of many signifiers of our identities, and to single out symbols that you are part of a religious minority does nothing to create a more equal society—it does just the opposite.

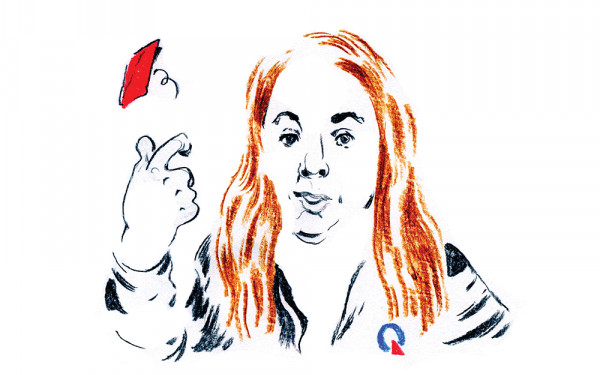

When MNA Françoise David mentioned she was opposed to a teaching environment where niqabs are allowed—ostensibly on the basis of feminism—Bacon read from an eloquent message the Simone de Beauvoir Institute sent to Concordia’s Board of Directors shortly after the charter was formally introduced, calmly exposing the flaws in her reasoning.

In its message, the Institute exposed the fact that a charter that dictates what women can and cannot wear, and that further marginalizes disenfranchised women, cannot be called feminist.

Taking care to continuously bring voices from the Concordia community to the commission’s attention—rather than relying solely on the administration’s point of view—Bacon and Côté demonstrated that students, faculty and the higher-ups can in fact band together.

It’s not only a heartening change from Concordia’s administrative history, it’s also a demonstration of how Concordia can handle assaults on its essential character in the future—calmly, compassionately and resolutely.

_600_375_90_s_c1.jpg)