Editorial: Were We Just Marois’ Pawns?

One year after forming a government in an election triggered by tuition protests, the Parti Québécois has launched a debate just as polarizing—if not more so.

The ongoing hearings on the PQ’s values charter show what op-eds on both sides have been claiming since its “leak” in September—that this whole debate is just thinly veiled Islamophobia.

Considering the PQ formed their government riding the wave of the Maple Spring, we can’t help but feel used.

The week before the September 2012 election, the words “A Deal With the Devil” appeared in block text on our cover. It illustrated a debate we’d had in our meetings leading up to the election: Could a progressive or federalist vote for the PQ without selling out their own values? With the best chance of unseating the Liberals, was a vote for the PQ endangering religious minorities for a tuition freeze?

A plan for a values charter was never hidden by the PQ; it was a clear part of their campaign platform. But what was less clear was how far it would go.

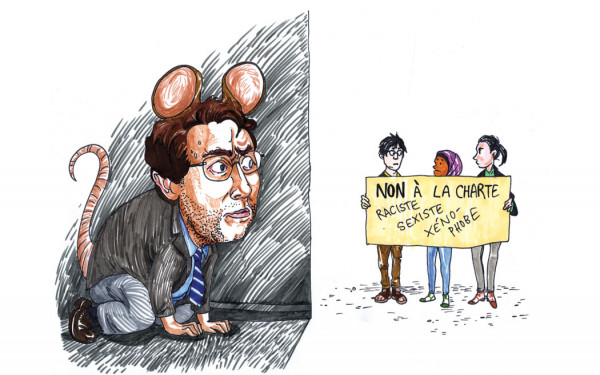

We’re now in the midst of a public spectacle—250 hours of testimony that, in his opening remarks on the first day of the hearings, Minister Bernard Drainville stated would not change Bill 60’s proposed ban on religious symbols for public sector employees.

With the latest poll numbers showing that the Marois government is in the best position for a majority since it took office, it now feels like we, as part of the 2012 student movement, were used by a politician wearing a red square when it suited her needs.

As far as the Maple Spring is concerned, we essentially got what we wanted. Though there are still student groups advocating for free tuition, the 75 per cent increase over five years was cancelled. Instead we saw a less than three per cent increase this year, and tuition increases are now tied to the average household income.

The special law putting restrictions on the right to demonstrate was also struck down. With both these moves announced the morning after her election, we couldn’t help but feel a sense of victory alongside Pauline, even if we hadn’t voted for her.

But that sense of victory is long gone, replaced with the bitter truth that the leading party is not capable of seeing the world from outside its pure laine point of view.

This charter—denounced by the Quebec Bar Association, unions, universities and the province’s own human rights commission—has brought Islamophobia’s ugly head to the forefront of political discourse. It’s allowed the rant of a man pick-pocketed in Morocco, and a woman being “scarred” by walking in a mosque to be part of the public record.

While the Liberals flounder in trying to come up with their own populist decision, the PQ line hardens.

As students demanding cancelled tuition hikes, we were catalysts to the PQ’s government, Marois quickly bottling the rage awakened by the strike. The government can argue the charter is meant to represent the secular nature of the state, but that doesn’t change the fact that the province’s religious majority will never be forced to choose between their job and their faith.

This charter does nothing to protect the people that its supporters claim are subjugated—it just denies them a chance to work in the public sector. It normalizes the persecution of difference in the public sphere.

This fear of difference is not exclusive to Quebec, but the government is both validating such thinking and giving it a platform.

It’s why Quebec women’s centres are reporting an increase in verbal and physical attacks against Muslim women since the charter was first introduced in September. It brings Quebec closer to Europe than Canada—in that this country does not have openly anti-Islam political parties.

That’s something that should be celebrated, but instead civil liberties are being attacked. And we just can’t shake the feeling that we’re in some way complicit.