Anti-Black Racism at Concordia: 53 Years of Inaction

University Apologizes for 1969 Computer Centre Protests

The President’s Task Force on Anti-Black Racism published its final report on Oct. 28, two years after the project first began.

The first of its 88 recommendations mandated the university apologize to every student and community member who was involved in the 1969 computer centre protests. It was one of the most violent events in Concordia’s history.

Concordia President Graham Carr issued a public apology in front of a crowd of Black community members and former students who lived through the protests. Carr apologized “for the harm that was caused to Black students at the university and for the negative impact felt by Black communities in Montreal and beyond.”

“It should not have taken more than fifty years to acknowledge the wrongs leading up to, and in, 1969,” Carr told the audience. “Now we begin the hard work of delivering on these recommendations and strengthening our relationships with Black communities, on campus and in Montreal.”

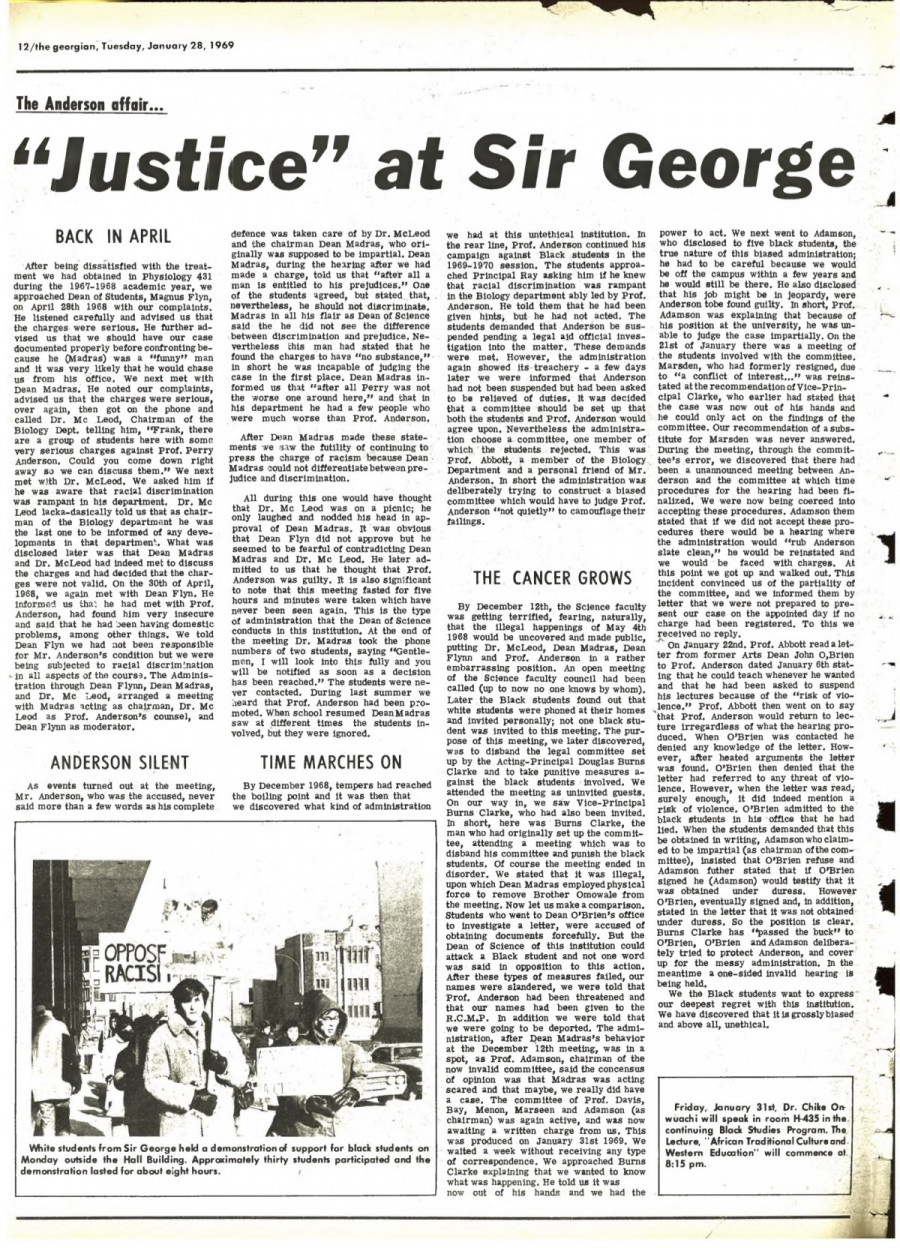

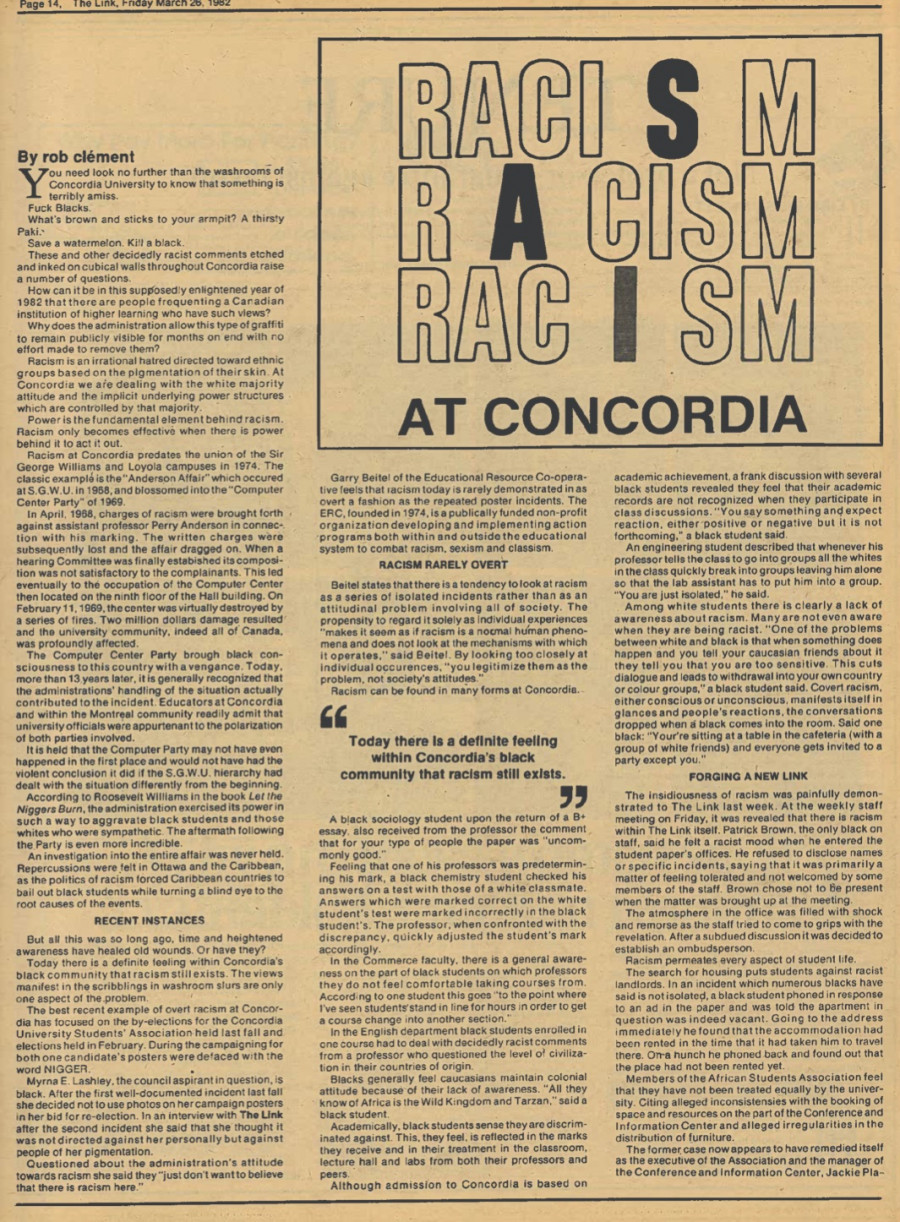

The 1969 computer centre occupation, commonly referred to as the “Computer Riot,” shook the foundations of Sir George Williams University and placed systemic racism in academia under a global spotlight.

Two students involved in the protests, Rodney John and Lynne Murray, were present for the apology. They thanked the administration for recognizing and apologizing for the pain inflicted on hundreds of Black students and allies a half-century later.

The origins of the protest movement were planted when a dozen Black and Caribbean students, including John, accused racist professor Perry Anderson of systematically lowering their grades. “It’s always ‘six students,’” John told the audience. “We were more like 12 or 13,” he said, correcting the common narrative.

John stated he was consistently at the top of his class, acing assignments left and right. He explained that when Anderson became his professor in the academic year of 1967-1968, something changed. Along with his fellow dozen classmates, he noticed the professor was docking points because he had a bias against West Indian students.

Recalling events that unfolded in a physiology class, John shared the experiences of fellow Black classmate Terrence Ballantyne. “He hands in the lab, Anderson marks the lab and gives him seven out of 10,” John said. “His [white lab] partner copies Terrence’s lab—He even copied the few grammatical errors Terrence had made.”

When Ballantyne’s partner received his identical lab report back from Anderson—which was nonetheless handed in late—the white student received nine out of 10 marks. “It’s not only that our work was judged inferior to that of white students, but that we were a priori judged not worthy of the marks we had acquired,” John said.

When Black students met with administration officials, their experiences were sidelined. Dean McLeod, chair of the biology department, defended the member of his faculty, and paid no heed to the students’ complaints.

“We were identified in the news media as Black students who could not make the grade,” John said. The university’s support for the professor and his racial bias were a catalyst for the computer centre protests in 1969.

Following a growing list of injustices against Black students at Sir George Williams University, a group of around 400 students blockaded themselves in the university’s computer centre on the ninth floor of the Hall building. Lynne Murray was amongst those peacefully protesting the blatant racism in the university.

“Students were forced to lay down on broken glass on the floor and were beaten with clubs.” — Lynne Murray

After a week of the occupation during the first week of February 1969, the university agreed to the students’ demands. The majority of students went home afterwards, but some remained. The university soon called the police on protesters.

“Feb. 11, 1969 was a dark day in the history of Montreal,” Murray said. Ninety-seven students were arrested, 42 of whom were Black. She recalled being beaten and tortured by the police. “Students were forced to lay down on broken glass on the floor and were beaten with clubs,” she said.

Murray was arrested by the Montreal police and jailed for several weeks. After being bailed out by her family, she accepted a plea deal and paid a fine for participating in social justice and anti-racist action.

Amid the violence unleashed on Black protesters, Coralee Hutchison, an 18-year-old from the Bahamas, received head trauma inflicted by the police. “She suffered a brain aneurysm and died shortly after. Her parents believe it was because of the beating she received that day,” Murray said. Concordia’s apology did not mention this potential connection to Hutchison’s death.

“We suffered humiliation and shame, the indignity and painful scorn of family and friends. We were incarcerated and branded as criminals,” Murray said. “And why? Because we protested against the racist actions of professor Perry Anderson.”

Murray criticized the university’s “deliberate misrepresentation and indifference,” but remained thankful an apology was finally issued 53 years later. She took time to highlight the successes of many of her fellow protesters in the years following the movement, including Canadian Senator Anne Cools and President of Dominica Roosevelt Douglas.

Additionally, Murray spoke on the importance of following through with the Task Force. “These plans you share with us today must be implemented and fully executed, and publicly demonstrated,” she said.

The 97-page Task Force report was broken up into four categories: Driving Institutional Change, Fostering Black Flourishing, Supporting Black Knowledges and Encouraging Mutuality. In total, 88 recommendations were proposed.

Angélique Willkie, associate professor of contemporary dance at Concordia and chair of the Task Force, spoke to The Link about the process behind the report. “It has been a colossal amount of work. I am extremely proud of the work that has been accomplished over the past two years, and the collective knowledge that has emerged. I am honoured and humbled,” she said.

Willkie said her humility towards such a project stems from the deep physical and emotional labour needed to create and implement the recommendations of the Task Force. “It’s not about saying ‘ look, we’ve done this.’ Yes, we’ve done this, but the implementation is more important.”

Implementing the work accomplished by the Task Force will require time, patience, perseverance and conviction, Willkie said. “I am aware of the moment of euphoria, and the work there is left to do beyond that.”

Atop the list of recommendations was the apology for the university’s mishandling of Black protesters in 1969. Willkie said addressing it was a necessary step. “Student voices were not heard; they were not considered legitimate. That is the reason the apology needs to be there,” she said. “It’s the reason we need to think about what took place in ‘69 and help us situate what has taken place, look at the silence, and address where we go, acknowledging that history.”

“What’s important is how that incident needs to inform the way we look at the 50 years of silence,” Willkie said. Her journey with the Task Force began in 2020, following the Concordia community’s demands to the administration for action on anti-Black racism.

From the beginning of the process, Willkie said her goal was to bring forth concrete solutions rather than mere proposals. “We didn’t want to come out with an idea of what should happen, we wanted to come out with ‘here’s what we do.’ On top of all the consultations, there have been regular and intensive exchanges with university units and sectors,” she said.

“Student voices were not heard; they were not considered legitimate. That is the reason the apology needs to be there.” — Angélique Willkie

Willkie believed that breaking down the recommendations into achievable, identifiable and specific formats, the university’s administrative body will be able to implement the changes successfully.

In front of the audience on Oct. 28, Concordia Provost Anne Whitelaw shocked many in attendance. “The university will implement all the recommendations included in the report,” she said. The room broke out into thunderous applause.

“This report provides a roadmap for how to make the university more welcoming, more just, and overall, a better place,” Whitelaw said. “Some of the recommended measures are currently being realized, or will start being realized shortly. Others require more time, coordination between units and funding.”

Some of the recommendations include the creation of a Black student resource centre, academic support, awards, bursaries and career advising. Additionally, the university will hire a Black faculty member to lead the development of Black and diaspora studies in the Canadian context, an important step in the creation of a Black Studies program.

Concordia also committed to increasing diversity within faculty, ensuring more tenure-track positions for Black professors in a multitude of disciplines. Additional resources will be invested to assure representation in STEM fields.

Whitelaw also announced Willkie would be continuing in her position as special advisor to the provost on Black integration and knowledges. Implicit bias training and anti-racism modules will also be produced for faculty and senior administration officials.

The most pressing section of recommendations, under the category Driving Institutional Change, included installing a plaque in Hall commemorating 1969 and renaming parts of the university whose current names evoke Concordia’s anti-Black and colonial legacy. The renaming commitments will be done by 2024 for the university’s 50th anniversary.

As the university takes on such an in-depth, systemic project, questions about implementation and accountability remain unanswered for several Black students. Amaria Phillips, co-founder of Concordia’s Black Student Union, spoke to The Link about her commendations and concerns.

My fear is that this might only be performative,” Phillips said. “Making sure that after the Task Force’s mandate is done and that the actions follow through is so important. Having conversations with the dean made [the administration] realize we are tired.”

“The Black Concordia community is tired of empty promises. When we see it, we’ll believe it.” — Amaria Phillips

Phillips was involved in several focus groups, roundtables and discussions where the Task Force sought student input. She was glad to give her feedback, but remains skeptical that Concordia will hold itself to task in delivering these recommendations.

One of the main goals of the BSU, Phillips explained, is to apply pressure on the university administration externally, focusing on Black students’ needs. “That’s something BSU will continue to do—making sure we’re listening to other students and keeping our foot on [the administration’s] necks to get the work done.”

While Phillips admired Whitelaw’s commitment to realizing every single recommendation in the Task Force, she questioned Concordia’s ability to do so. “The university probably has good intentions and will try as best as they can, but a lot of us are side-eyeing them. Racism is not new in this school. They just apologized for something that happened 50 years ago.”

“The Black Concordia community is tired of empty promises,” Phillips said. “When we see it, we’ll believe it.”

This article originally appeared in Volume 43, Issue 6, published November 8, 2022.

_900_506_90.jpg)

_600_832_s.png)

__600_375_s_c1.png)