Why There’s No Malagasy Neighbourhood in Montreal

The Community That Lays Low

Vanilla extract, screaming lemurs and a golden sunset over red endless dirt plains—that’s Madagascar, or at least those are the prevailing stereotypes about it.

These clichés are dominant to this day, although Malagasy people have spread throughout the world, leaving small traces of their culture where they’ve settled. In fact, there’s a Malagasy community right here in Montreal, though you might not know it.

Josoa Randrianaly left Madagascar at a young age to pursue his studies in Russia and then later in France, where he obtained a Master’s degree.

“When I moved here, it was a time in my life when I missed Madagascar a lot and I was very keen to be part of a community,” Randrianaly said. He went on to say that in France, it was frowned upon to be part of a foreign community and not assimilate to French culture.

He moved to Montreal in 1999, freshly graduated from a French university, because he had a better opportunity here. What attracted him to Canada was that the immigration process was easier than other places, as he could become a Canadian citizen after three years.

For a long time after his arrival in Montreal, Randrianaly acted as the rassembleur in the Malagasy community, which was composed of 1,685 people in 2006 in Quebec, according to Statistics Canada. That number only counts people born in Madagascar.

“There’s a high demand for a community here in Montreal, the need is there,” said Randrianaly.

However, the Malagasy community in Montreal is practically invisible to other Montrealers.

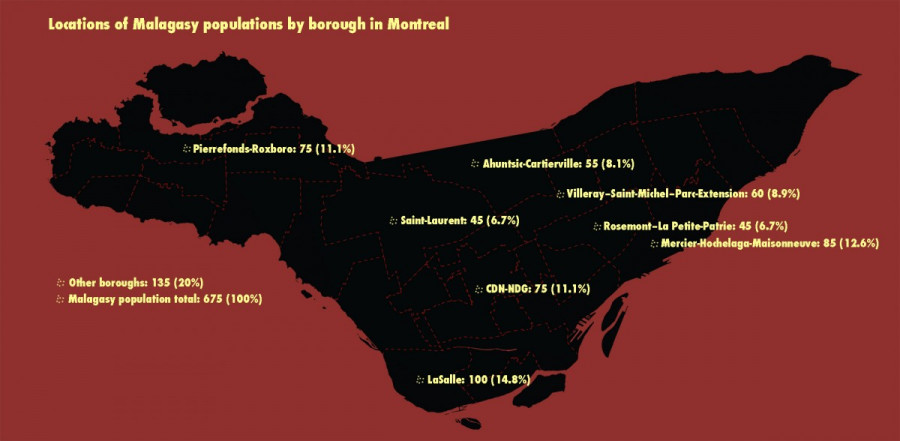

Unlike Chinatown and Little Italy, where a cultural community congregates in a geographical zone, there is no visible Malagasy ghetto, and there probably will never be. Instead, immigrants from Madagascar spread out through the island and its suburbs by choice.

One of the reasons for that, according to Lovasoa Ramboarisata, professor in the Strategy, Responsibility and Environmental department at UQAM, is because the community is not large enough yet. Still, no matter the size of the community, she says Malagasy people like to mix with the population d’accueil and other communities in the city.

“Even if we were in a situation where we could form a neighbourhood, we don’t follow this same model as other cultures,” Ramboarisata said.

Malagasy families here in Montreal are often in a good financial situation, according to Randrianaly. They have the luxury to decide in which neighbourhood they want to live, depending on their needs and desires, whether that’s on the island of Montreal or in the suburbs. Usually, people congregate in ghettos because the housing market is most favourable in a certain area.

“When Malagasy people come here, it’s with a student visa or as qualified workers,” Ramboarisata said.

Malagasy immigrants in Quebec are highly qualified people with 45.3 per cent of the population holding a university degree, as compared to the 16.5 per cent of the Quebec population as a whole.

“At home, things are not getting much better,” said Ramboarisata on the subject of the unstable political situation in Madagascar. However, there is no civil war in Madagascar, so its migrants cannot enter Canada as political refugees like those from countries like Syria, for example.

Typically, Malagasy people leave the island off the west coast of Southern Africa to immigrate to France, but Ramboarisata went on to say that the immigration politics in France are not as welcoming as in Canada.

According to a French governmental site, there are about 70,000 Malagasy people living in France, which is approximately 42 times more than Quebec.

Nevertheless, both Ramboarisata and Randrianaly have seen the Malagasy community grow over the last few years.

“When I first moved here, in 1999-2000, there were about 20 or 30 families here, but now there are so many more that I can’t recognize everyone during the cultural gatherings,” Randrianaly said.

Ramboarisata expects the community to keep growing with Trudeau’s new Liberal government, which has a more open immigration policy than the previous Conservative government.

Despite the growing number of Malagasy in Montreal and the rest of Canada, the community will most likely never ghettoize, said both Ramboarisata and Randrianaly.

From the outside, the Malagasy community may seem somewhat dormant, but from within, there are many occasions to gather.

Although they might be invisible to the outsider, there is a great sense of community that exists from within. The community likes to congregate around hobbies like art, culture and religion.

There are numerous events that happen throughout the year like the Rencontre sportive Malgasy in North America, which happens in a different city each year—Montreal hosted it in 2014. There is also a language school and the Association des orateurs, which shows the richness of the language, said Ramboarisata.

Typically, one of the most sharable characteristics of a country and culture is the food. There are very few Malagasy restaurants in Montreal, perhaps the most notable being Tsak Tsak—which can be translated into “snack” in English—on Beaubien St. near Jean Talon metro. It’s popular, but Ramboarisata suspects that it might be because they’ve adapted to the Canadian audience by serving brunch food.

“I love the food of my country but it’s very particular, visually speaking, and for its taste,” said Ramboarisata.

“There’s a saying in Madagascar,” Randrianaly said, to explain the fact that Malagasy people don’t seem to regroup when they are abroad. “To keep a good relationship with your close ones, you must drift away from them.”

In a previous version of this article, the author stated that Montreal hosted the Rencontre sportive Malagasy in 2008 instead of 2014. The Link regrets the error.

_900_675_90.jpg)

_600_832_s.png)