Who Can We Trust With the Keys to the Ivory Tower?

The Repeated Failures of Our Black Leaders

When the Balarama Holness 'scandal' came out, I overlooked it. I thought this was yet another Black person in power who failed to meet the bar of Black excellence which is set in heaven.

Right before the 2021 municipal elections, it was reported that members of Holness' non-profit, Montreal In Action, mass resigned. This included the majority of both his board and executive team. A chaotic and alienating work environment and loss of confidence from the board towards Holness ultimately led to five out of six members resigning in late 2019.

Not long after, more resignations followed suit. They included the two seasoned activists and Black women Catherine Diallo, the former co-chair of research and advocacy, and volunteer Shalaka Shah.

When non-white public figures are embroiled in political drama, the criticism always seems to echo the loudest. The media scrutiny and the wrath of social media always become most violent when they exit the depths of Twitter and enter our daily conversations and classrooms.

I was also tired of the never-ending blabber of the world and made a habit of ignoring most scandals or abstaining from commenting in any kind of public format. I had no doubt there was some justification for the social media uproar, but too often, its volume was disproportionate to the alleged offense.

But I found myself beginning to relate to Shah and Diallo when I encountered my own Balarama Holness a few months later.

My experience was all too similar to the shared experience of many women of color just like myself. A leader, in my case, the former general coordinator of the Concordia Student Union, whose regular misogyny, unjustifiably large ego and crippling incompetence derailed the goals of the union—I worked for and negatively impacted my well-being and job satisfaction.

As the Equity, Diversity and Inclusivity manager of the union, it was my job to ensure the equitable treatment of all employees. It, therefore, became my job to ask, uncover and document the accounts of abuse and harassment experienced by many employees, mostly women. This too took its toll on me as the complaints became a daily occurrence and the behaviors of the perpetrator dangerously increased in boldness.

Yet, no one seems to discuss the emotional toll of the psychological harassment of being at the mercy of such egoistic leadership. Inevitably, I too reached my breaking point. Despite all the rewarding work I had already put in, the many projects still underway or the indescribable fulfillment my work had once brought me.

This didn't stop him from claiming all criticism was racist and unwarranted. He claimed victimhood despite having never issued an apology to any of his victims, aside from requesting to speak to me once his impeachment became imminent, which I respectfully declined.

As the brilliant actress, writer, producer and comedian Issa Rae once said, "I am rooting for everybody Black." But those same people would not care about me if their positions didn't require my vote or if there wasn't any clout to be gained from exploiting black suffering and turning it into a commodity.

What would happen if we could conceive of the nuances of a Black man in power? Comment and criticize the individual as a reflection of their character rather than their ethnicity. Maintain the focus on their poor leadership skills, communication skills, organizational skills, or better yet, the harm their sheer incompetency can cause, especially when directed at their own people.

Should we not subject our Black leaders to more scrutiny before seeking to empower them to represent us in rooms most of us will never even have the chance to walk into?

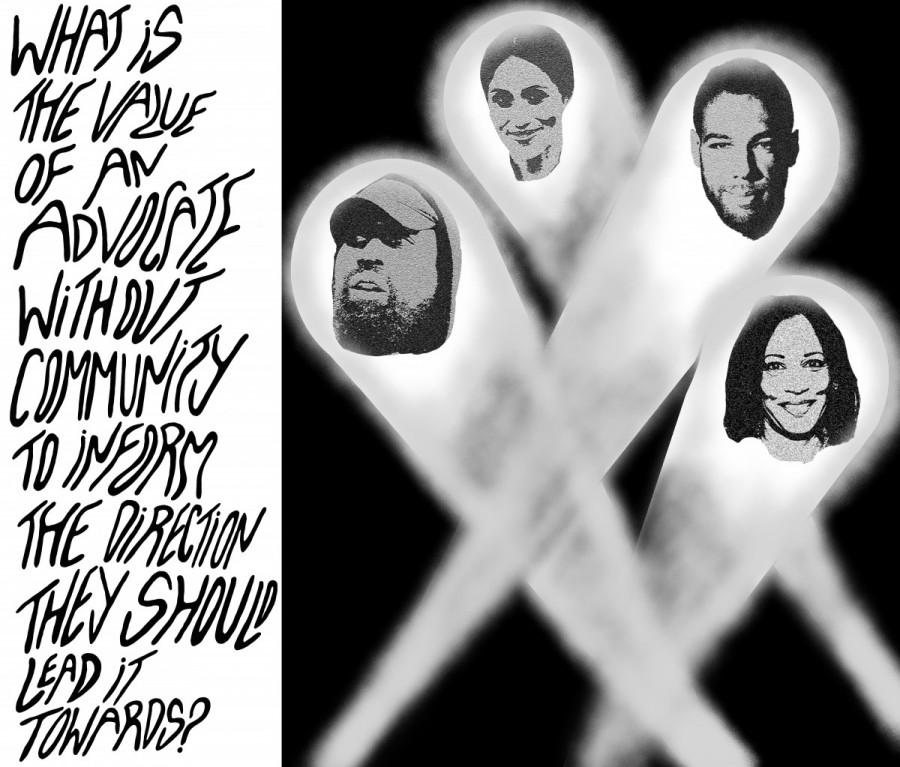

Not for the sake of seeking perfection or (Black) excellence, but rather to ensure the continuous aim for social justice. What is the value of an advocate without a community to inform the direction they should lead it towards? One who vaguely gestures at everything else as the culprit of the criticisms they refuse to face when we dare inquire about motive, competency or objectives. Willfully ignoring the harm they have caused so that the image of themselves they have so carefully constructed remains uninterrupted.

Sounds like communal narcissism to me, but what do I know? So what happens once those types of people are given the keys to the ivory tower?

In sociology, the term ‘habitus’ refers to the ways one person's unique experiences influence their perspectives on the world. It helps raise questions like "Who is your loyalty to?" or "How do you define your morality?"

French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu, in his oeuvre of the same name, then adds the notion of distinction. In other words, what distinguishes those with the upbringing and resources necessary to be given access to so-called high society? Those without it may never hold the keys to the ivory tower. These proverbial rooms are what Bourdieu refers to as fields—social spaces in which specific discourses and institutions, like a classroom, church or congress, can be found.

Every field has power struggles within them to determine what does and doesn't belong in it and allows gatekeepers to uphold those boundaries and reward or punish people within it. So if economic capital is not a viable option for Black leaders to get into the fields that hold power over large communities and populations, social capital, such as a hurting community, must then prevail in its place and grant them access.

From Kanye West to Candace Owens or from Kamala Harris to Meghan Markle, these individuals weaponize Blackness by exploiting the painful experiences of the Black community out of convenience, not benevolence. Once they have their set of keys, they rejoice in the money and power that comes with it and leave the rest of us to fend for ourselves. Make no mistake, our collective outrage and hurt is a commodity that rises in value every election season.

They will freely criticize others for doing less than what they never truly intended to do or will inevitably fail to realize. But a seat at the table does not guarantee a plate, and soon they breadcrumb us with unfulfilled promises as they reappropriate the meaning of community out of necessity rather than care. Where would you guess the allegiance and loyalties of such a person lie?

I never truly understood the depth and toll of the harm caused by this type of false leadership until I witnessed it first-hand. Truly, until it was aimed directly at me. It was enough to make me walk away from a position that came with many benefits, none of which were worth my sanity or health. But the failure to properly vet our leaders comes at the cost of the progress of the Black community.

Black leaders especially have often put emphasis on the accumulation of political power (or social capital). The Obama presidency, for instance, represents the culmination of those efforts for many. But often, Black-driven political clout comes at the expense of true Black economic and social advancement.

Has political success truly been a major factor in the historical upward social mobility of disenfranchised groups out of poverty? Can leaders elected on social capital truly have an understanding of the issues at hand? Are they both experienced and empathetic enough to pursue policies that actually create the change they campaigned on? Are they able to apply pressure regardless of being disliked because they prioritize the importance of success over the perception of their image?

I have seen a lot of moral entrepreneurs and peacemakers in these positions; the self-appointed kings, queens and representatives of Black people. But I have yet to see someone who I can fully trust with the keys to the ivory tower.

I personally want a Will Prosper rather than a Canadian Barack Obama to represent me in these rooms. I don't want the promise of change under the guise of benevolence. I want someone who has been and continues to be in the trenches with the rest of us.

Perhaps then, the ideas of people that look like me are what the political agenda is based on rather than what our labor is exploited over for a talking point or a mere shield for any form of criticism.

Maybe then, the keys are for us all and the kingdom becomes ours instead of at the mercy of a greedy undeserving king whose throne is made of the sweat and tears of the people that got him there.

I know of a certain general coordinator (and self-appointed king of Black people) who, once removed by his own people, refused to give back the keys to the kingdom. Forcing his constituents to bear the cost of the replacement of every room he still demands access to.

This article originally appeared in Volume 43, Issue 4, published October 12, 2022.

_600_375_90_s_c1.jpg)