The tweet that started an Iranian movement against sexual violence

Journalism in 2021: How a personal experience of a journalist affected a patriarchal society

It was a summer night in 2017, a few months after I had immigrated to Canada. I was waiting in front of a hotel in Toronto to interview an Iranian artist.

It was the first time I was working as a journalist outside of Iran, and I felt confident and free. We met in the hotel’s main hall, where I asked to start the interview.

“I will talk to you after you come with me to a party,” he said. “Let us spend the night with each other, and I will answer all of your questions.” I was shocked and could not move a muscle. Without my consent, he put his hand on my arm and smiled. I knew that smile well. I knew that body language well. When I was living in Iran, I had faced similar unprofessional behaviour many times, but I did not know I could consider them as harassment.

I am not alone in this situation. According to a recent study done in Iran, ninety percent of Iranian journalists who are women have experienced harassment during their job, at least once. Most of these harrassments were in the form of inappropriate language, being asked to have sexual relations, or being touched without consent.

However, I did not expect to have the same experience in Canada. That night, I did not know how to react professionally against such behaviour. I was scared to show my protest to him. I was a journalist and I could not believe my power to write about it or show my feelings. I felt insulted and cancelled the interview. I chose to be silent.

I preferred to continue my silence for all these years. The silence was rooted in the internalized fears caused by Iran’s patriarchal society. If a woman wants to take action against any violence she has experienced, she will face many problems like being rejected from their family and can even lose her job. The assumption is that the woman is always guilty.

Following that night, I kept asking myself, “When will this silence be broken?”

The answer came three years later, from another woman journalist.

In September 2020, Sarah Omatali, a former Iranian journalist living in the U.S. broke her long silence about sexual harassment. "This was an expedient [silence], because I was not brave enough to speak about it and even face the consequences" she tweeted.

Omatali revealed that about 14 years ago, she was sexually assaulted during a professional meeting with Aydin Aghdashloo, one of Iran’s celebrated visual artists. Omatali suffered from this incident for years but did not feel brave enough to share her experience. But after 14 years, she wrote a tweet telling the world what had happened to her.

“These kinds of violence are common against women journalists in Iran,” she told an Iranian website. “I wanted to give a voice to other women journalists to share their experience with harassment.”

The New York Times reported that at least 45 other journalists said that they have been victims of sexual harassment by Aghdashloo and that three of them wanted to see him prosecuted.

Omatali’s coming forth was the beginning of a major campaign launched by Iranian journalists against violence and sexual harassment. This campaign soon became a movement like #MeToo and was supported by many journalists, artists and activists both inside and outside of Iran.

Many Iranian women shared their stories, experiences and the identity of the violators on Twitter and other social media.

“I used all my journalism courage to encourage the women who have many fears and limitations to speak about their experiences and to tell them they are not alone,” said Omatali in an interview.

If this movement continues to grow and not stay limited to the women who could share their experiences, we will gradually see more actions taken to battle violence against women in Iran .

The long lasting effects of this movement can already be seen. The Independent Persian reported that the Tehran Journalists Association launched a committee to support all the women journalists who are victims of violence.

Also, around 1000 Iranians living in Toronto signed a petition asking the board of directors of the Tirgan Festival, the largest celebration of Iranian arts and culture outside of Iran, to stop their collaboration with Aghdashloo and other alleged artists. One of these artists is the man I met in the hotel that night.

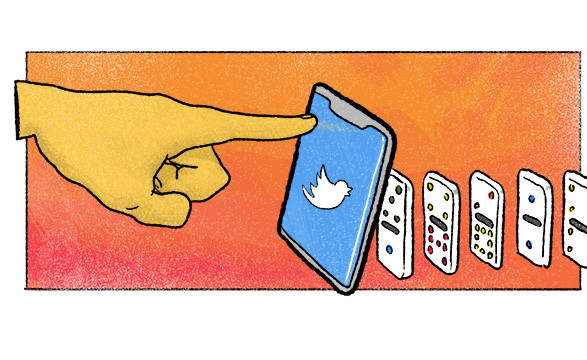

As an Iranian female journalist, I learned that big changes can start from a small tweet.

An individual woman journalist could influence an entire society by sharing her own story.

Personal experiences of any journalist are important, whether she is proud or ashamed of them, whether she has a fear of expressing them or has coped with them. These experiences are authentic, tangible, and might be felt by a large part of society.

Thus, these personal experiences give journalists the opportunity to give a voice to those who do not have a safe place to share what has happened to them if she decides to. There are many people who have experienced similar moments to what I experienced that night in Toronto. I want to break my silence and be a journalist for them.

This article is part of a series which discusses different aspects of journalism as a way of keeping a record of the scope of the profession in 2021. Topics range from the impact of gender in journalism to its history.