The patriarchy-resisting power of female punk

DISHPIT uses music as empowerment in debut album

It’s not every day that you witness two women in dominatrix outfits dress up their male drummer in a diaper and whip him while walking through their audience to circus music, as Nora Kelly and Jed Stein of DISHPIT once did at a concert.

Montreal post-punk/grunge trio DISHPIT uses their moody, eccentric, and ferociously freaky sound to subvert a male-dominated industry and shine a light on the female experience. On March 12, after a long and complicated record label journey and nearly a year of COVID, DISHPIT released their debut album DIPSHIT. Although the pandemic has stifled the band’s ability to host concerts, the trio is finding new ways to empower through performance.

The band, a trio of Concordia University alumni, is comprised of front-woman power-duo Nora Kelly and Jed Stein with Ethan Soil on drums. Lead vocalist Kelly writes the songs and plays guitar while Stein writes the bass lines and comes up with the backup vocals.

Finished back in November 2019, DIPSHIT has been a long-awaited release for the band. After the rep of their first record label gradually stopped answering to any form of correspondence, supposedly vanishing off the face of the planet, DISHPIT had to wait for their contract to expire before being able to release their music legally. “It’s just been this sort of uphill battle for a long time, so it’s nice that the album is finally coming out and the rights of our music are back in our hands,” said Kelly.

“[We are] being these women who are bold and kinda crazy and take up a lot of space on stage and aren’t afraid to make mistakes and scream and be kind of uncensored in a field where more and more women are playing music,” explained Kelly. “It’s kind of exciting to be like these rocker dudes, but we’re women.”

Because the music industry has historically been a male-dominated field, female singer-songwriters have continuously struggled to create music that speaks to them and isn’t influenced by or filtered through male standards.

“Music has this unique power to give voice to those who are silenced, and women have long been silenced,” said Sandi Curtis, a professor emeritus at Concordia in music therapy.

She is hopeful this is changing, however. “We are seeing more women singer-songwriters getting out there and adding their subversive voices against patriarchy,” she said.

Influenced as teenagers by riot grrrl figures such as Kathleen Hannah of Bikini Kill, DISHPIT is currently inspired by bands such as The Breeders, Slint, and Modest Mouse. “[We’re] playing with the genre, not taking it too literally but having that attitude,” said Kelly.

Punk aficionado Jeff Parkinson, who came across the band’s music via some early demos for DIPSHIT, has become a fan of the band and their vision. “I think they are kind of like the only band around that is doing music like that now, no one else really has that kind of energy and aggression.”

DISHPIT’s ability to weave the personal into activism sets the band apart. “They’re like little pop songs, but heavy pop songs, so they have like the grunge element to them but Nora is really good at the hook, so they’re all catchy, and I think that’s quite unique,” said longtime friend of the band and former collaborator Colin Spratt.

“Music has this unique power to give voice to those who are silenced, and women have long been silenced.” — Sandi Curtis

“It’s slow then fast; ahh, it’s fantastic,” Spratt said. Self-trained musicians, the band often writes in odd time signatures, a characteristic that has become central to their sound.

Nora and Jed met in their first year at Concordia within the stone walls and loft ceilings of the Grey Nuns Building. “Even before the band was official, I would go to [Jed’s] room [...] [S]he was really good at guitar. It was kind of just like kindred spirits,” Kelly said of their early days as friends.

The group began casually, without much intention, said Kelly, but they soon started playing house shows and small venues. Eventually, the band began to see the potential for something more serious. Kelly and Stein were quick to fall in love with performing live, their absurd energy and offbeat minds finding a home in the punk show scene.

“Prior to the pandemic, we were always trying to come up with crazy stage antics and gimmicks,” Kelly said. During one Halloween show, Kelly performed with gushing blood capsules in her mouth and on other occasions there have been kazoo solos.

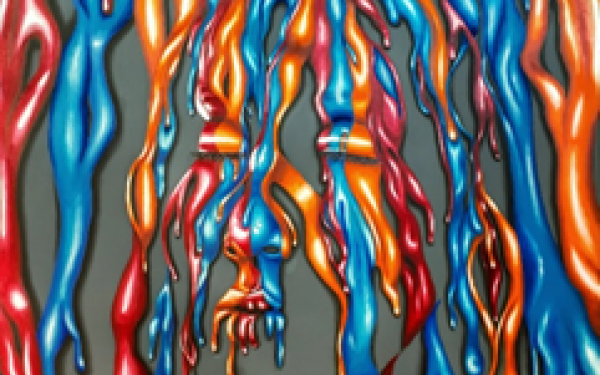

Kelly explained that with COVID-19, the band has shifted to using music videos to achieve a similar sense of empowerment and catharsis. The video for “This Time,” the first song released off the album, aims to de-stigmatize the shame around talking about sexual assault and open up conversations about traumatic experiences.

“I wanted this song to add kind of a voice to survivors of assault without it being too blatant or triggering, to try and have it be more in the abstract,” said Kelly. “The music video is supposed to have a sort of empowered undertone, where eventually we get on these motorcycles [...] and go off into the sunset.”

“As important as the music is, I think the video is important too because sometimes women singer-songwriters have lyrics that are quite powerful, but [...] the video uses them as sort of eye-candy, objectifying the women and not empowering them,” said Curtis.

This is because not only are the recording agents and producers primarily male but the music video directors and producers as well. The way Curtis sees it, it’s not that men in the music industry have the intention of preventing women from being heard, but more so that when they listen to music by other men, they can instantly relate.

“[T]his understanding that we are each these static individual people that were always consistently the same is a fallacy,” said Kelly. “You could wake up one day and be in a terrible mood and do all sorts of things that you couldn’t have imagined you’d do the week before,” said Kelly. From a sleazy lady in the song “Trash Queen,” to an unstable hermit in “Plaza People,” to a money-centric valley girl in “Sold Out,” DIPSHIT is a rollercoaster of character portraits, explained Kelly.

“You can listen to a song and it might be somebody else’s story, but maybe one line in that song resonates for you,” said Curtis. She explained that the power of words married to music affects people emotionally, physically, and cognitively all at the same time, rendering it an incredibly powerful medium.

“Women can put their own stories into their own songs and then those are amplified by their listeners, their fans, as they hear their own stories that are very unique to themselves yet have some universal truths to women of all areas, all walks of life,” said Curtis.

This article originally appeared in The Resistance Issue, published April 13, 2021.