The difficulty of speaking French while non-binary

Tackling inclusion in gendered languages

French is an inherently gendered language, creating some complications for non-binary French speakers.

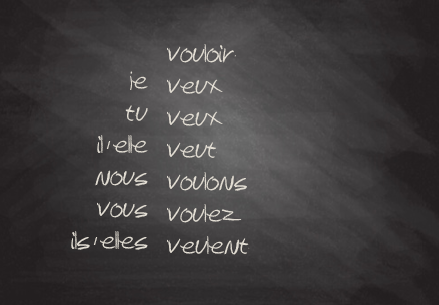

Though French stems from Latin, where there’s a neutral form, this neutral form became assimilated by the masculine one—which is why masculine words are still used as neutral today. So, to communicate in French, not only are there binarily gendered pronouns, but each noun has a gender, and the rest of the sentence must agree with that gender.

“It’s something that I think about every day,” said Ambroise Vanasse, a non-binary Concordia French major. French being their first language, they always have to be conscious of their adjective agreements and the way they speak.

In French, they use the pronoun eux, which translates to “them” in English, though it does not share the singular form of its English equivalent. While eux is still a gendered pronoun (its feminine counterpart being elles), to Vanasse, it just feels right. When referring to themself, they don’t use adjectives, but rather find a way that they don’t have to make a gendered agreement. For example, instead of saying “je suis chanceux/euse,” they say “j'ai de la chance,” avoiding the agreement.

Vanasse said it’s stressful to always be thinking about, but that’s the way it is. “I like the fact that French is really complicated. But I would like if a new form would be invented, like a neutral form.”

“I think there’s always that fear of being too complicated to understand, but my gender is very fluid and complicated, so it’s kind of representative of that too.” — Gabriel·le Villeneuve

For Concordia student Angel Langlois, being non-binary and speaking French are almost mutually exclusive.

Though they did all their schooling in French until university, they feel like a lesser version of themselves in French circles.

“I feel like I have a lot more ability to explain in English because there's more language surrounding [being non-binary]. But I felt super alienated; I've almost entirely stopped engaging in French,” they said.

Langlois finds the neo-pronouns iel and ille “clunky” and avoids using adjectives. They ask people to use their name rather than pronouns, but if they must use pronouns, to use the masculine form because they’re feminine presenting. “It’s not entirely comfortable for me, but it’s more comfortable than the feminine pronouns.”

“Having pronouns respected really does have a benefit to people's mental health,” said Laura Shearer, a Concordia graduate student. Though they’re American and speak English as their first language, they have a long history with French. They studied it in high school, majored in it as an undergraduate, and spent about two and half years studying and working in France.

“Both of the areas I lived in in France, Dijon and Nevers, were more conservative. So I made the conscious decision to stay in the closet. But one of the things that was on my mind was how would I be able to work with this language given that it's so gendered?”

“I feel a lot more understood and seen when people use my pronouns. It’s not the other way around.” — Gabriel·le Villeneuve

Shearer currently lives in the U.S. but is planning to move to Montreal after the pandemic. They aren’t sure how they’ll handle the gendered language but they’re considering just constantly switching the genders when referring to themself.

They worry, however, that their anglophone accent might cause people to view it as “a sign of ignorance of the language or a sign of disrespect to the language’s rules, instead of actually knowing the form well enough to improvise off it.”

Gabriel·le Villeneuve is doing their masters at Concordia. They also do freelance work, primarily for the LGBTQA+ community therefore, the gendered nature of French is something they constantly have to think about.

Villeneuve uses the iel pronoun, but they understand others’ hesitance to use it: “I think there's always that fear of being too complicated to understand, but my gender is very fluid and complicated, so it's kind of representative of that too.”

They also use interpoints when writing their name to make it more neutral. At first, Villeneuve was concerned that it would reinforce the binary, but a friend of theirs gave them a different perspective. “They told me that the interpoints were beautiful in the way that they have a circle in the middle, and that a circle can really represent infinite possibilities,” reflecting Villeneuve’s view on the infinite possibilities of gender.

In terms of making changes, they explain that there’s still a lot of work to be done. “I feel like change has to start from the speakers and not really from the authorities.” Villeneuve themself is involved in this process through education work on the subject.

“The problem is that until recently, neutral just meant including women and men.” — Julia De Marco

Dr. Danièle Marcoux, director of the COOP program in translation and associate professor in Concordia’s French department, explained the push for a more inclusive French began with the feminists in Quebec in the 1970s. They fought for feminized job titles and so they wouldn’t be grouped in with the “neutral” masculine form.

The Canadian Translation Bureau now has a guide to writing and speaking in more inclusive French. It suggests using neologisms—which are newly coined words or expressions, such as the pronouns iel or ille—or modifying certain endings of words to be more neutral, among other solutions.

“The problem is that until recently, neutral just meant including women and men,” said Julia De Marco, a Concordia masters student in translation. She explained that slowly, some language authorities, such as the Federation québécoise de la langue française and the Canadian Translation Bureau, are making progress, but it isn’t widespread or accepted by all of them.

“I think it'll probably take a lot more discussion, a lot more debate, and a lot more people standing up for themselves, unfortunately. But I think just by making these guides or writing these papers that are more open to the public, that's already such a good start,” she said.

Marcoux worries, however, that though she wants to include everyone in the language, all these changes will make it impossible to understand one another and will be challenging to write.

De Marco doesn’t share this concern, saying that languages are meant to evolve and it’s necessary to make these adaptations.

“Language changes every day,” she said, explaining that every word started off as a neologism. “If anything, I think language has to adapt to the times. We're not speaking now the same way that we were 100 years ago, and that's completely normal.”

Furthermore, Villeneuve explains the goal of reimagining language isn’t to make things more complicated but to put into words notions that have always existed. “If anything, it makes room in the language for more nuances. And that's important because there are nuances in life and in human beings. I feel a lot more understood and seen when people use my pronouns. It’s not the other way around.”

Until inclusive language is normalized on a larger scale, Vanasse’s advice is to always ask people how they’d like to be referred to—not just in French, but also in other languages. For gendered languages particularly, it’s also crucial to consider adjectives and agreements. “Don’t assume, ask, and don’t be afraid to ask a lot of questions.”

A previous version of this article referred to Dr. Danièle Marcoux as an assistant professor, and not an associate professor. The Link regrets this error.

This article originally appeared in The Gender & Sexuality Issue, published March 10, 2021.

_600_375_90_s_c1.jpg)