Surviving and overcoming sexual assault in the Canadian Armed Forces

Julie Marcotte is one of many whose assault was dismissed by commanding officers

“Men should go to war, not women. They’re too weak.”

TW: This article discusses sexual assault and rape.

This message was made clear to Julie Marcotte when she first joined the army. “Being a woman in the army is tough, men don’t like having us around,” she said. “It isn’t jealousy, it is the mirror of a society that defines roles.”

Marcotte was 17 when she joined the army. Not too much of a school person, the promise of camping and spending entire days outdoors encouraged her to enroll. “The reality is that at the time, they had to fill quotas of women,” she said.

She moved to St. Jean-Sur-Richelieu for an eight-week program after which she could eventually decide not to join the Canadian Armed Forces. Yet, after this basic training, she decided to enroll for the next three years with no chance to drop. “Once you get in, it’s almost as if you were married with the army. It is exactly like a sect. You must accept all its aspects, even the ones you would reject in another context.”

Among such aspects, peer abuse is one that Marcotte had to deal with from the early days. Right at the beginning of her engagement, she could feel that some of her male colleagues didn’t like having a woman in their team.

Abused by her peers

While a part of Canada's artillery division, Marcotte endured several aggressions from her peers that remained unpunished. It started when she intentionally got hit in the face by one of her colleagues. When she tried to speak up and denounce her aggressor, Marcotte was told it was an accident and she shouldn’t make a big deal out of it.

At the time, Marcotte didn’t know such an aggression was only the beginning.

Later in her training, Marcotte got raped several times at the back of a truck. Her aggressors were her peers from her unit. There were six of them. The most disturbing fact is that the rapes were ordered by her superior, “a physically imposing man whose hierarchical status protected him from any accusations,” she explained.

To justify such a call-to-action, the officer said that if sent to a conflict zone, Marcotte might be the victim of sexual aggressions and she’d better be prepared for it. Again, when she tried to speak up, she was dismissed and disregarded by the chain of command.

After these tragic events, Marcotte received many death threats from the men that assaulted her. “They would knock at my door to tell me that if I were to speak up, they would lose their reputations and families. They told me they’d make sure I disappear if I were to denounce them.”

Marcotte’s story isn't one of a kind. Even today, women in the CAF are victims of sexual assault.

The 2016 survey on sexual misconduct in the CAF conducted by Statistics Canada revealed that sexual harassment and assault within the Forces have various roots. They include the sexualized culture of the CAF, the problematic policies, the insufficient training, as well as a lack of action by the leadership.

Anne Hurtubise, executive director of the Quebec Veterans Foundation, claims the army, at the time, was a hostile environment for women. Equipment is not adapted to their shape and consequently, many of them get injured.

During her time at the artillery division, Marcotte, as the only female artillery rank member, had to share common showers with men. “As the only girl, I used to shower at night. I didn’t feel comfortable having to shower with them.”

“They would knock at my door to tell me that if I were to speak up, they would lose their reputations and families. They told me they’d make sure I disappear if I were to denounce them.” —Julie Marcotte

After years of suffering in silence, Marcotte eventually switched divisions and became an aerospace control officer for two years. She started having migraines linked to her post-traumatic stress disorder. At the aerospace division, officers are not allowed to take any medication. Since her migraines got more and more intense, she was forced to be laid off from the CAF.

“Whenever I talk about something sad, he feels it and comes close in order to calm me,” she said about her dog Bernie who'd just jumped into her lap.

Back at home, a slow but lasting recovery

Like many other veterans, Marcotte’s first years of transitioning back to civilian life were complicated. A 2011 joint survey by the Department of National Defence and Veterans Affairs Canada showed that 25 per cent of veterans reported a difficult adjustment to civilian life.

Hurtubise claims the transition is even harder for the ones who were laid off for medical reasons like Marcotte.

According to Marcotte, VAC offered really poor services at the time. “I think I fell between the cracks of the system,” she said. “Between 2003 and 2014 I spent my entire time trying to find little jobs here and there by myself.”

After 10 years, VAC called to offer her money after they realized she’d been out of the help system. It’s helped her to go back to school and she now takes photography classes.

Joining the Invictus Games

In 2017, Marcotte heard of the Invictus Games. The Games, organized by Prince Harry, are designed for people who were physically or mentally injured while serving in the military. In order for all participants to be able to play together, non-disabled people must learn how to play in a wheelchair.

Marcotte applied and began a one-year training in two new sports: recumbent cycling and wheelchair basketball. "It was difficult. Players who are already used to moving around on all four wheels, the chair is an extension of themselves. For me, it's an addition, I had to relearn how to play completely,” she explained.

Marcotte won two medals in cycling, one silver and one gold awarded by Prince Harry. “I was proud, I really felt like I was serving my country,” she said.

According to Hurtubise, the Games give participants a chance to be challenged in a team setting with other veterans again. “Such games are therapy, they are so valuable in the veterans recovery,” said Hurtubise.

The games occured when Marcotte started being more open about what happened to her and felt more confident in advocating against sexual assaults within the CAF.

Yet, at the Invictus Games, like in the Forces, there’s a taboo about mental injuries, “If you didn’t lose a leg at war, you deserve less to be there,” said Marcotte.

Right after winning the medal, Marcotte said in an interview that she wasn't there because she lost a leg on the field but because she got sexually assaulted and that resulted in PTSD. This interview created a movement, she contributed to raise awareness on the matter. Many women who suffered from similar experiences were calling her and telling her their stories.

“It was the first time someone would talk out loud about it, suddenly, it became a legit issue,” Marcotte said.

In 2019, the Federal Court approved a $900 million agreement that will settle multiple lawsuits by individuals who suffered from of sexual harassment and assault in the military. Depending on their situation, veterans are eligible for between $5,000 and $55,000.

A further $100,000 goes to people subjected to exceptional harm, such as those who suffered from PTSD from the way they were treated.

It was only this year that the CAF opened the Office of the Status of Women and LGBTQ2 Veterans to better support female veterans in their transition to civilian life.

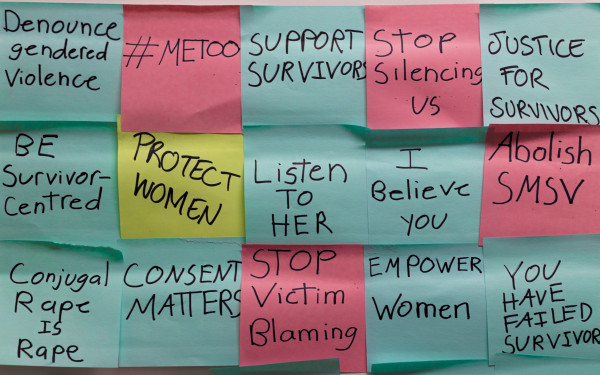

They’ve launched a campaign against sexual violence and harassment in the Forces that has seen the creation of a number of initiatives and institutions to support victims, including the Sexual Misconduct Response Centre.

This article has be corrected to refer to Marcotte as an artillery rank member, not an artillery officer. The Link regrets this error.