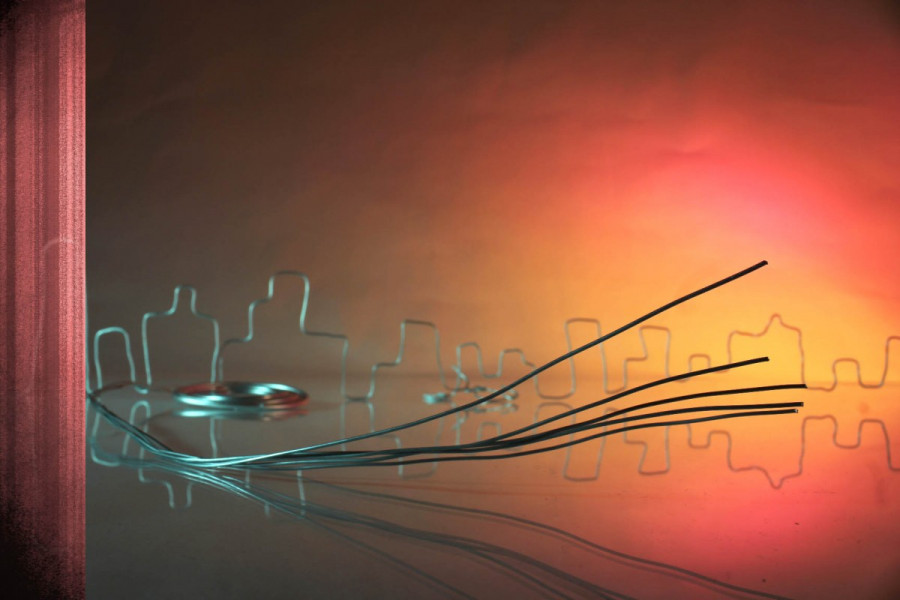

Streams of Information

The End of the Newspaper’s Monopoly and How it Intends to Survive

Every year, fewer people pick up issues of the newspaper you are holding.

In the early 1980s, The Link held a monopoly over the attention spans of Concordia students. While lounging between classes, students didn’t have access to the Internet and its infinite power of distraction. The halls reverberated with conversation and paperbacks were read, but the only real connection to the wider world was a copy of the newspaper.

That monopoly has now been broken, in these pages, as it has in every other publication in the world.

First, the bad news: across the world, the revenues of newspapers have plunged and aren’t recovering, staff is being laid off in record numbers, issues are getting thinner in both words and impact and newspapers are shutting down.

Despite the disintegration of a press system that took centuries to build, the world’s consumers of news and information have never had it better. Streams of information from around the globe are carrying ever more information, faster, to their media tool of choice.

“The monopoly of locked-down information and locked-down media is gone,” said Tim McSorley, a member of The Dominion’s editorial collective. “There isn’t a closed network anymore and there are ways that it can be changed without locking the news down again.”

The incumbent giants of the media universe have tried many ways of dealing with the challenge of the Internet; they are now talking about taking the information off the free Internet completely. No one is more serious about pay walls and online memberships than Rupert Murdoch, the head of News Corporation—the parent company of the Fox network.

“People will be buying papers and enjoying the tactile experience for decades,” said Murdoch, 80, last year. “Soon people will be getting stories over WiFi to their eReaders, and we will be able to charge them a very attractive price.”

The Australian media mogul has already put The Times of London and The Wall Street Journal behind pay walls, readable only after netizens have paid the cover price.

Last Wednesday, Murdoch launched his newest venture, The Daily, an iPad-only newsmagazine that features short-form stories for a dollar a week. The critics have not been kind to the new product, pointing out its lack of unique content and its appeal to the lowest common denominator.

While some have called Murdoch’s approach “fearful of the future,” other newspapers have embraced the Internet.

“I expect that one day the newspaper will be a luxury item, a lot like a magazine, when you pick it up in its physical form once a week,” said Matt Frehner, The Globe and Mail’s mobile editor. “The bulk of the news business is moving online.”

Having inked a 20-year printing deal late last year, the Globe has embarked on a plan to remake itself for the 21st century. The widely applauded redesign of Canada’s national paper last year was the first step.

The Globe is not betting its future on a pay wall, but rather on being the first online source of news for Canadians and delivering stories faster than the competition. The paper version will slowly become more of a magazine, delivering the long-form experience and colourful layout that readers seem to appreciate on paper.

Despite the plan, Frehner admits it’s a gamble.

“Everything is changing so quickly right now. We seem to be at a point of transition,” said Frehner. “In three years our mobile traffic is supposed to be higher than our web traffic. We aren’t sure where we will be five years from now.”

This is not the first challenge newspapers have faced—but it may be the last.

Radio was supposed to kill news publishing, but the threat never quite materialized, as the spoken word never delivered as much detail. Televisions were the next challenger, and while the six o’clock news was responsible for ending evening newspapers, morning editions continued to flourish.

Many journalists felt that the Internet would follow the same script. However, plunging circulation numbers have yet to change course.

“The Internet is different; it is the closest challenger to the newspaper because it is text-based,” said McSorley. “Although people aren’t looking at long features online, they still love reading the news. Stories have gotten shorter, moving to tweets and blogs.

“Television stations are hurting, radio is hurting, but newspapers are hurting the most.”

The New York Times, the paper of record for the most powerful empire in history, is struggling under an immense debt burden. Last week, the Times announced that the last quarter of 2010 saw its revenues drop by 26 per cent below the previous year.

Within the next five years, the Times will almost certainly be extinct in its print form. The looming question is, will the newspaper build a pay wall around its online presence?

“You can’t put the genie back in the bottle. News has been going up for free, and I’m curious about how companies think they can lock it down again,” said McSorley. “But the media can be rebuilt in an open setting.”

McSorley’s publication, The Dominion, is reader-supported using a model like the American Public Broadcasting System. It doesn’t rely on advertising revenue.

OpenFile, a new collaborative news service spreading across Canada’s major cities, relies on citizens to file story ideas that are then assigned to reporters across the country.

“There is a need for paying journalists a wage and there is a need for organizations to create quality news,” said McSorley.

While blogs and Tweets form a new backbone of the information system, newspapers will remain around for decades—the printed edition may die, but the great names will live on in one form or another.

Those expressing concerns about the sustainability of Murdoch’s “fear of the future” may be onto something. While researching for this story, a Wall Street Journal article had great quotes from Murdoch; the media mogul’s future thoughts may stay trapped behind his own pay wall.

This article originally appeared in Volume 31, Issue 22, published February 8, 2011.