Special Issue: Fighting Our Own Biases

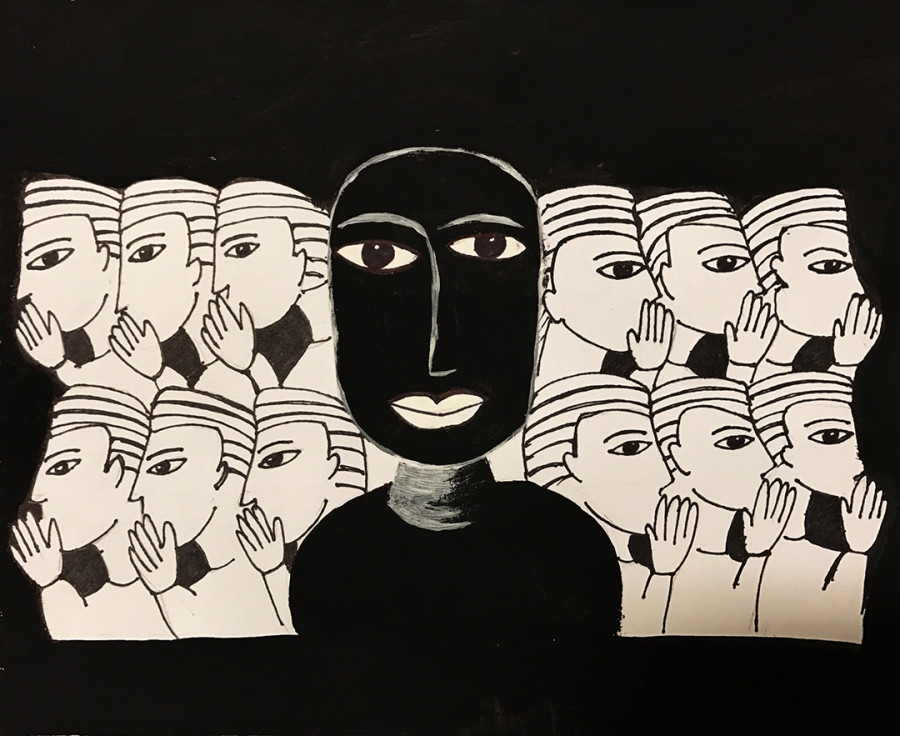

It’s all a minstrel show. Everything. It never went away—it’s just been redefined.

A few months ago I was waiting for the 105 bus at the stop by Loyola campus. It was late at night, I had just finished work and I was eager to get home. As the bus pulled to the curb, a group of three young women, who I assumed came from the residence, ran towards it. Having just made it, proud of their impeccable timing, one of them exclaimed, “Nigga, we made it!”—an obvious reference to the Drake song.

Now I’m faced with a dilemma—do I say anything?

Another one of the women immediately scolds her jubilant friend for uttering the word. There’s a small back and forth between the two. The woman who made the initial reference insists she doesn’t normally use the word but she’s really drunk. Her friend insists it’s still not okay.

Do I interject at all? I have to be careful. Will I seem antagonistic? Will this cause a larger situation to develop?

Racial minorities must always keep these thoughts in mind. You have to think about how the way you respond to something will be perceived by others. This is one of my more extreme examples but there are others.

I’m a tall guy so I get asked from time to time if I like basketball. I don’t dislike basketball, but it’s not my favourite sport. I’ll get asked if I like rap. Yes, I like rap, but why is that the first genre to pop into people’s heads? People will sometimes say some questionable jokes or observations in front of me and someone is bound to say, “Oh he’s not really Black, so it’s fine.”

What does “really Black” even mean? Am I not Black because I don’t act a certain way?

What does “really Black” even mean?

In any of these situations I have to gauge how I respond because, again this could create a larger situation. It could cause me to not “be cool” and not know how to “take a joke,” because all these situations are funny, you see, so funny in fact that I currently don’t have the mental capacity to process all that humour. It’s something I’m trying to work on.

It leads me to wonder: what is a person’s place in society? Not just any person—someone from a minority group. How is it that if we speak up, we have to worry about reprisal? What does it say about our place in a white society?

I call it the ongoing minstrel show.

It’s the term I use to describe how Blacks, or any minority, are viewed by a predominantly white society—at least in what has been termed Western civilization. I came to this realization after watching Spike Lee’s Do the Right Thing. In the film, there’s a moment when Mookie asks

Pino how he can dislike Blacks when his favourite idols—with respect to film, sport, and music—are Black. Pino replies that they’re more than Black, they’re different.

Different is the key word. It tells me that Blacks have their set space in society and that space is for entertaining—the minstrel show. Anything else beyond that, too bad, it’s not for you. This is what’s safe and digestible to the white population.

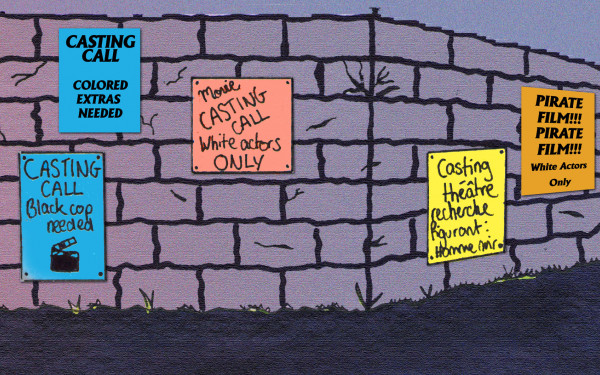

How many Black actors can you name? How many Black singers? Athletes? Now how many Black Prime Ministers have there been? Premiers? Presidents? Governors? Senators?

How many unarmed Black men have we seen killed over the past few years?

Ask yourself, why is it that police can apprehend someone like Dylann Roof alive, who murdered nine Black people during a church service, but Tamir Rice, an innocent Black child, ends up shot and killed?

This isn’t a simple issue of representation. It can help, but media trivializes and no single tweet, movie, TV show, actor, or law will fix this. Exposure to other people and other ways of life and thinking are good. Increased diversity is good, but the danger is that we become complacent with the status quo because we think, “Oh well, minority groups are being represented in various media,” while meaningful change hasn’t been affected.

The issues are too complex. There needs to be a fundamental shift in the way we think about Black people, as well as other minorities, and their place within our given society.

So what can you do? You might think that all this stuff isn’t your fault, that it’s just how it is. The world is a messed up place. While the world might be messed up, it’s not just how it is. Choices have been made and deliberate actions have been taken to lead us to this very moment.

You have to get involved. It doesn’t take much, but you have to be willing. You have to want to learn. You have to be able to question your assumptions and biases about how you see the people around you and what kind of value judgments you place on them.

Go look up what a minstrel show is. Go look up what lynchings are. Go look at the photos of those who’ve been lynched. It’s painful, shocking and disturbing. I know because I’ve looked it all up. I’ve seen the photos.

I don’t want you to simply feel remorseful for the victims, but I want you to notice the crowds of people surrounding the bodies and ask yourself, “Who is the real monster?”

This is not to say that white people are evil. No ethnic group is evil. Good and bad exist among everyone. It’s not about placing blame. It’s about reevaluating how we see ourselves and others.

Ask yourself why it is that if a Black person commits a crime, the narrative becomes “all Black people are criminals,” but if a white person or a group of white people commit a crime the narrative doesn’t vilify white people.

You might hear from people—I don’t want to say white nationalists, because this can come from people who aren’t as extreme—that providing various opportunities to minorities takes away from whites and that it’s not fair. Now it’s discrimination against whites.

So yes, slavery is over. People aren’t being lynched. Both those things are great and people don’t have to worry about that too much, but there’s more to be done. We can do better.

You should want to be better. We can all be better, together.