Sexism and Racism Continue to Dominate Sports Journalism

The Fight for Equality Is Far From Over

In the late 1970s, Concordia University journalism professor Linda Kay became the first-ever female sports journalist at The San Diego Union-Tribune, then known as the San Diego Evening Tribune.

Over time, she was eventually accepted by her sports editor and even became friends with him. However, her other male colleagues weren’t as kind.

“My mail was read,” she explained, “just to find stuff on me.”

Between 2011 and 2015, TSN 690 producer and host of Centre Ice, Robyn Flynn, found herself working alongside two other sports journalists, Jessica Rusnak and Amanda Stein, in what would usually be a male-dominated work environment.

While three women might not seem like a lot, “if you look at other sports radio stations, they have no women—maybe one,” said Flynn. “To work at a station that had three women at one time was something kind of special that [didn’t] exist anywhere else.”

Flynn found herself to be the subject of sexist remarks and offensive criticism.

In 2015, she wrote an article criticizing how the NHL dealt with forward Patrick Kane’s sexual assault allegations. Rather than suspending him until the issue was resolved, the Chicago Blackhawks organization held a press conference. Kane refused to answer questions about the accusations. A few days later, Chicago gave away Kane bobble heads at a game.

After the article dropped, Flynn began receiving hateful messages on Twitter.

“I got [messages] like ‘I hope you get raped.’ They were graphic like, ‘Someone should rape you with a hockey stick until you die,’” detailed Flynn. “Stuff like that […] and, ‘You’re just jealous because Patrick Kane would never rape you.’”

While Kay and Flynn’s experiences are different, these are but a few examples of the type of abusive and intrusive treatments that women in sports journalism have to deal with on a daily basis.

Issues of sexism are only exacerbated once female sports journalists make the leap into the professional world, despite the progress they’ve made over time. It’s unlikely that there is a single woman in this field who hasn’t experienced some form of misogyny.

Some journalists have already given up on a career in sports journalism because of these circumstances, or have at the very least, considered doing so.

Shireen Ahmed, a Pakistani freelance sports journalist and social activist, witnessed firsthand the concerns of many aspiring women at NASH, a Canadian journalism student conference that took place in Fredericton, New Brunswick this January.

“I can’t tell you the number of women who came up to me and said, ‘We’re really interested in becoming aspiring sports writers but we don’t think we fit in,’” she said over the phone.

Lack of Inclusivity

Many people are led to believe that the world of sports journalism has become more welcoming to women, and that any issue of gender equality has been resolved.

Yet it’s a known fact that men dominate all multimedia platforms in North America.

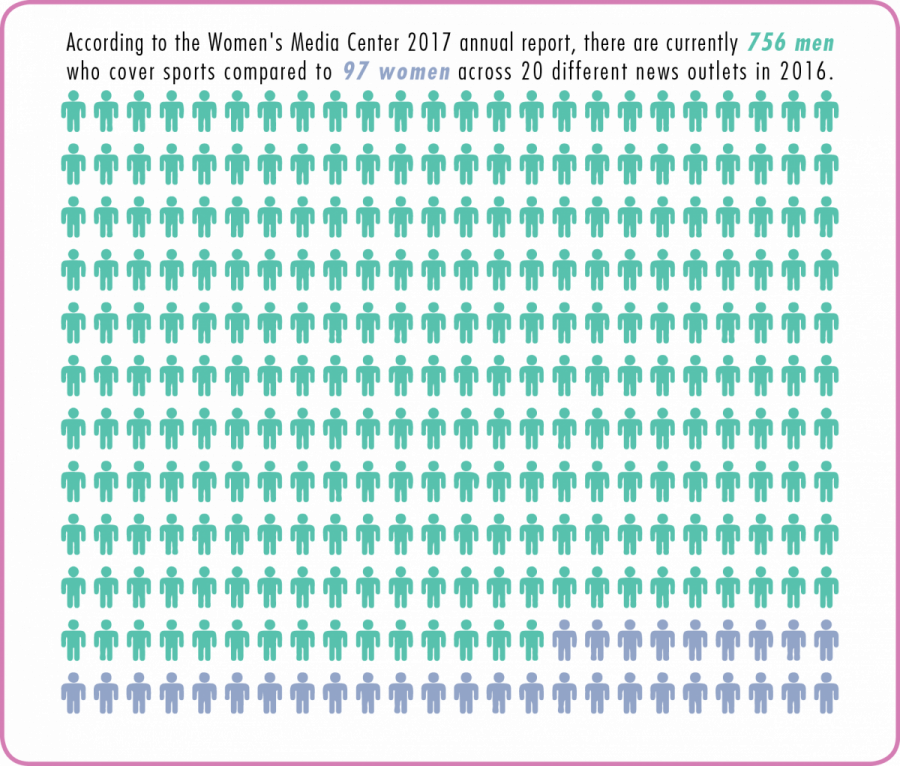

Female sports journalists remain the least represented in all types of journalism today. According to the Women’s Media Centre, only 11 per cent of women in the United States cover sports, while men cover 89 per cent. Moreover, “the number of female assistant sports editors at 100 U.S. and Canadian newspapers and websites fell by roughly half between 2012 and 2014—from 17.2 percent of all such editors to 9.8 percent.”

There are several reasons for the decline of women in this field. Kay mentioned that some journalists want to start families and the long hours of working weekend games can be arduous. But she highlighted that the harassment women get on social media is one of the biggest challenges to deal with—something she never dealt with as a reporter in the pre-social media age.

“That’s a hard thing to deal with on a day-to-day basis,” she said.

The fear of dealing with sexist, racist, violent or sexualized social media backlash if they present a wrong fact or a difference in opinion from their male colleagues or audience members also makes this field daunting. And while men still have to face criticism, the nature of the insults often target their intelligence, rather than their gender.

“We have to work twice as hard—which is exhausting—and you’re going to get a lot of flack,” said Flynn. “I think a lot of women just don’t want to deal with it. And I don’t blame them. It’s really, really hard to open up your Twitter and for no reason, just randomly, all of a sudden someone is threatening you or calling you the ‘c’ word.”

Progress, with Room for Growth

Fortunately, the field is improving for non-male reporters. It’s becoming more common to see women on television screens presenting and explaining game highlights and hosting panels during game nights on TSN and Sportsnet. Jennifer Hedger of TSN and Chantal Machabée of RDS have become household names for their audiences.

Moreover, ever since Flynn became the first woman in Canada to host a sports radio talk show, others that have emerged around the country. However, she’d like to see more women occupying positions where they can analyze sports and present their own opinions. For now, many female sports journalists are either sideline reporters or hosts, which limits them to presenting facts and letting others—their male colleagues—to share their astute analysis.

There needs to be more female role models in sports journalism in order to attract more women to the field. Women need to see that they can thrive in male-dominated jobs. Flynn recalled wanting to be a play-by-play sports commentator from a young age, but didn’t have any female role models to look up to. Her mother even told her, “It’s true, girls still don’t do that.”

Flynn decided to try her hand at broadcasting when she first found out about Andie Bennett, a CBC sports reporter who used to work at TSN 690.

“Andie Bennett was sort of the first woman […] I heard have an opinion about sports,” said Flynn. “And that sort of was a game changer for me.”

It’s not just about having more women either. People of color are also a minority in sports journalism. According to the 2014 Associated Press Sports Editors Racial and Gender Report Card, more women and people of color—regardless of gender—have been seen at ESPN.

However, the report card still displayed some troubling statistics. In 2014, across news outlets in the U.S. and Canada, 91.5 per cent of sports editors were white and only 9.5 per cent were women. These numbers were similar across other sports journalism positions as well.

Ahmed believes that including a variety of voices and increasing the presence people of colour will be key for a progressive future for sports journalism.

“For far too long, sports was literally the white guys speakers corner,” she said. “Wouldn’t you want to engage and challenge your readers to something different?”

Sexism and racism are pervasive ideologies that won’t go away overnight. In order to overcome these struggles, Ahmed feels that it is important to form a “sisterhood of other sports writers that are female and are important to your career.”

“I feel like it’s probably the only reason that I survived as long as I have,” she said.

Correction: Linda Kay was the first-ever female sports journalist at The San Diego Union-Tribune, then known as the San Diego Evening Tribune, and then later at the Chicago Tribune, however she only had experiences during her time at the San Diego based publication. The Link regrets the error.

_1_600_375_90_s_c1.jpeg)