Redefining sports journalism

Shireen Ahmed refutes objectivity, and fights for authenticity

On a very early Saturday morning in Toronto, before the second COVID-19 pandemic lockdown hit the city, Shireen Ahmed was driving her son to volleyball practice, and rushing back to make it on time for the women’s Manchester derby, the game between soccer giants Manchester City and Manchester United. She was going live on her podcast, Burn it All Down, virtually alongside her co-hosts to discuss the match.

This is one of the many things Ahmed takes on in her life. Born in Halifax to Pakistani parents, Ahmed’s passion for sports began when she was five years old, playing soccer. Now, she’s a writer, public speaker, and an award-winning sports journalist who focuses on Muslim women in sports, and the intersections of racism and misogyny in the field, while also hitting the soccer field every now and then. She has had work featured in Sports Illustrated, espnW, The Guardian, Teen Vogue, Globe and Mail, CBC, and many others.

Ahmed is a single mother of four, a friend, an optimist, a Muslim, and, above all, a sports activist.

“The term was christened by Sertaç Sehlikoglu, and I say christened ironically,” Ahmed says with a smile in her voice. “I met her just through the interweb, and I said I will write for you, I’ll give you your content because I need to practice.” Sehlikoglu, a Cambridge PhD and cultural anthropologist with a focus on Muslim women in sports, had started a blog in Canada called “Muslim Women in Sports”—exactly Ahmed’s field of interest. The PhD candidate was Ahmed’s editor for a while and helped her frame her analysis in a critical way, Ahmed said.

Writing critically comes with the implication that the concept of objectivity, once at the centre of what journalism meant, is challenged. The debate of what objectivity really means is as old as time, but Ahmed doesn’t only challenge the norm—she refuses to adhere to it.

“People can accuse you of being ‘unobjective,’ but my job is to report fairly, it’s to be accurate,” Ahmed said. “This idea of objectivity is ridiculous because it was created by gatekeepers of journalism trying to tell people from the margins that their lived experience affects their work. Well, show me one journalist whose life doesn’t affect their work!”

As a veiled Muslim woman who is athletic and engaged in the world of sports, it was natural that she would tackle the issue of the portrayal of Muslim women in sports media. One of the platforms she uses as representation is the podcast she created with four other women over three years ago, Burn It All Down. The five women come from a mix of racial and academic backgrounds: Brenda Elsey, associate professor of history in New York; Jessica Luther, freelance sportswriter in Texas; Lindsay Gibbs, sports reporter and writer to The Athletic in Washington; and Amira Rose Davis, assistant professor of history and women’s, gender, and sexuality studies in Pennsylvania.

“She has taught me most of what I know and understand about Muslim women in sports,” said Ahmed’s podcast co-host and good friend, Luther. “She has taught me about unfair hijab bans, Iranian women being banned from football stadiums, and the efforts of women in all parts of the world working towards their own liberation via sports.”

Ahmed believes sports and politics are inherently political; and removing the prior from the latter is an act of privilege, not an accurate reflection of reality. She says sports isn’t just about analytics, play-by-play, and statistics, but also about “people, their struggles, their glory, and about how they use sports to express themselves.”

She believes in the difference between objectivity and accuracy in reflecting the population, recalling once when she approached a fellow journalist and activist, Desmond Cole, through Twitter, asking “how do I push back?” His response held such immense power for Ahmed that she still quotes him today:

“This idea of the journalist as a pure lens is nonsense and I reject it. All journalists are biased. I try to be open about my biases rather than pretend I can stand apart from the world I interrogate. I am a product of that world, and I am directly shaped and biased by my experiences of it.”

“This idea of the journalist as a pure lens is nonsense and I reject it. All journalists are biased. I try to be open about my biases rather than pretend I can stand apart from the world I interrogate. I am a product of that world, and I am directly shaped and biased by my experiences of it.” – Desmond Cole

So, how does Ahmed push back? She says “facts have to be corroborated, information must be accurate, but to report from a lens that somebody else who’s privileged and will never be me thinks I should? I don’t accept that at all.”

The act of rejection of the status quo is one of the ways Ahmed is a sports activist. In February of this year, Ahmed took part in TEDxToronto, where she spoke of her experience as a Brown woman sports journalist, and the role people can play in changing the current exclusive norm of the sports world, into a more inclusive one.

The title of her segment with TedxToronto was the Sports Stories You Haven’t Heard. She addresses the stories that are left untold, mostly because, as she described, someone who hasn’t been through a lived experience can’t accurately portray the truth—this is the issue of a single-lens approach to sports media. Fighting back tears during her presentation, Ahmed spoke of two occurrences that pushed her even further into journalistic activism in sports. The first was about a Black high-school varsity wrestler named Andrew Johnson in New Jersey, who was forced to cut off his dreadlocks or risk being cut off from the competition. Johnson cut his hair, and the local media dubbed him the “epitome of a team player.

“In order to compete, Andrew was expected to shed a part of his identity because it was considered ‘unnatural’ by the white referee,” Ahmed says. This is the other side of the coin when it comes to inclusivity in sports for Ahmed: it’s not just who is reporting, it’s also how someone is being reported on.

Another reality that shocked her and is still an ache in her heart is one that’s worlds away across the world from North America. In Iran, women are not allowed to attend games inside stadiums. Ahmed spoke of the times women and girls had to dress up like men to sneak past watchful guards and into the stadiums. The particular instance that solidified the inseparability of politics and sports, she continued, was the court hearing of an Iranian woman, known as Blue Girl, who had heartbreakingly set herself on fire in the middle of the court, and passed away six days later.

This oppressive law against Iranian women was established following the Islamic Revolution in Iran in the 1980s, Ahmed said. She is openly critical of the way governments and people around the world use Islam, despite some pushback from her own Islamic community saying she shouldn’t propagate such a negative portrayal of the religion.

“My job isn’t to be like a PR person for Islam, the religion doesn’t need me to do that,” she says, adding that “this isn’t a problem with Islam, this is a problem with men in the system. It goes back to people contorting faith to suit them, and that’s not how it works, but that’s what men do. I say men because they’re the ones that are in charge of decision making in a religious and sports context equally.”

The key to change in Ahmed’s perspective is in the hands of the decision-makers—and according to her, this starts with more people of diversified backgrounds demanding to be heard. Ahmed had begun her own career with a Tumblr blog—and she continuously urges people to use the space social media offers as a platform.

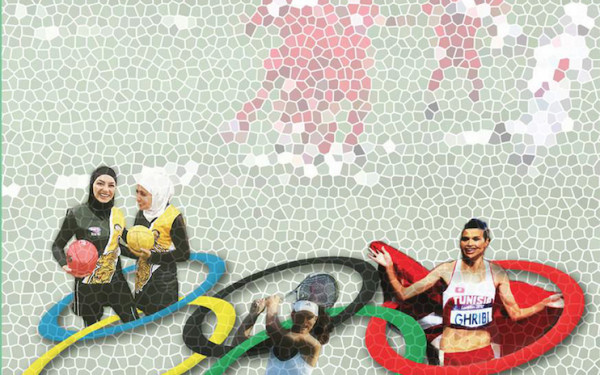

“We need people from all racial backgrounds and gender identities to help sports media grow to something that truly reflects the population,” she says. Ahmed hopes to represent not only Muslim women in sports, although that is her focus, but also to highlight the real impact that diversifying the sports system can have on world-issues such as misogyny, racism, and xenophobia.

As a five-year-old, the little girl with long black braids in a polyester red and yellow striped kit felt like she belonged on the field where the ball wasn’t discriminatory. Now, as an adult, she hopes to pave the way for more kids who might feel like they don’t belong to start believing otherwise, in a place where people aren’t discriminatory.