Quebec’s Student Movement Fights Against Student Poverty

Groups Like ASSÉ and Comité unitaire sur le travail etudiant Trying to Reform the Student System

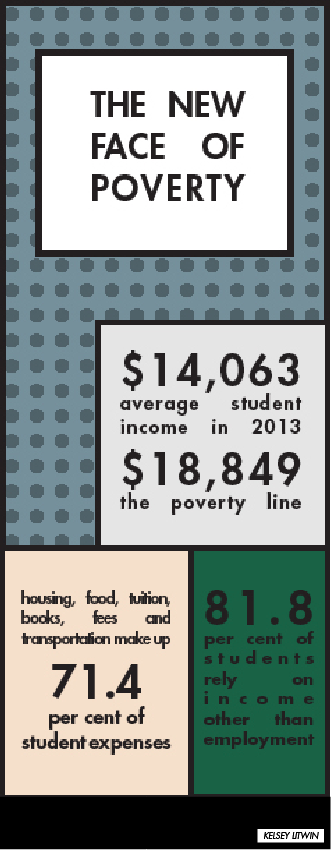

Students in Quebec today face a series of micro-economic crises that, together, create widespread student poverty and precarity.

This poverty manifests itself in a number of ways. Over 40 per cent of students across all forms of higher education amass “medium debt” during their studies, defined as anything from $10,000 to $24,999, according to a 2015 report by the Minister of Higher Education.

Students work unstable low-wage jobs, often in the service sector. Students are generally expected to work unpaid internships as a form of training.

“Young people entering the job market are at the bottom of the totem pole, employment-wise,” said Jamie Robinson, an office assistant at Concordia Student Union’s off-campus Housing and Job Bank. “We have a shrinking employment economy, and it’s those people that are the first to go.”

“Companies aren’t offering full-time employment, they’re offering part-time and contract work—which is inherently precarious,” said the HOJO employee.

Robinson also said universities themselves contribute to masking the full extent of the youth unemployment rate. “People are coming to school because they can’t find work otherwise,” she said, “or the jobs that are available require a Master’s degree.”

Robinson explained that this is a way for companies to offshore training costs to public institutions, and that it is a symptom of neoliberal austerity.

Based on what she’s seen at HOJO, she explained that finding work at all is very difficult for students. She says her organization sees a large amount of illegal internships appear in its job bank, many of which directly target students. She encourages students to learn how to recognize when internships are actually just unpaid labour.

An unpaid internship in Quebec is only legal when it fits into at least one of three legally defined categories—if it is overseen by a job training program, it is part of schooling, or it is for a non-profit organization with community benefit. Any other “internships” are illegal, unpaid labour.

Students in Quebec are notoriously resistant to accepting poor conditions. Ever since the Quiet Revolution, they have organized to defend and advance their interests.

The Association pour une solidarité syndicale étudiante is a federation of student unions throughout Quebec with over 70,000 members, including the Fine Arts Student Alliance and other departmental associations at Concordia.

The federation launched a campaign against the student precariousness in November. According to Rosalie Rose, ASSÉ’s spokesperson, the campaign will be multifaceted and tackle different symptoms of student poverty.

“We’re demanding a $15 per hour minimum wage,” Rose said. “And for Quebec’s regions, we demand that it be higher because of the higher cost of living.”

The movement for a $15 per hour minimum wage is picking up steam in Quebec well beyond the student movement. Demonstrations in favor of the wage-increase topped 1,000 people this fall, and over two-dozen groups have joined the “fight for $15.”

ASSÉ is also demanding that all university internships be paid and that the institutional barriers for student access to financial aid be abolished.

Rose specified that the parental contribution—where some students are not “poor enough” to access financial aid due to their parents’ economic status—is particularly problematic for a number of students.

In order to mobilize for these demands, ASSÉ has been working on organizing its members through visibility actions in schools. Rose says ASSÉ has dropped banners, helped organize protests and held workshops and trainings on the subject in schools.

Outside of schools, Rose said the federation has been building coalitions with other groups. She says ASSÉ has allied itself with community organizations and labour unions through the Red Hand Coalition. It is also working on building institutional solidarity between the student movement and other social movements.

Beyond the official institutions of the student movement such as ASSÉ, students are also organizing at a grassroots level. Last spring, CEGEP Marie-Victorin created the first Comité unitaire sur le travail etudiant.

Other CEGEPs and universities have since created branches, and have formed a decentralized network of campus-level organizations. CUTE’s main demand is that students be paid a salary, similar to the student salary that exists in Denmark.

The stipend-type program gives all Danish students the equivalent to $900 USD a month, with no repayment expectation. The only condition is that the students not live with their families.

“Students are poor because their main job isn’t recognized as work and thus isn’t paid,” said Thierry Beauvais-Gentile, an organizer with CUTE.

“CUTE considers all students, at all levels, student-workers,” Beauvais-Gentile said, explaining that already-existing unions of teaching and research assistants should be expanded to include all students.

“We believe all student work should be considered valuable work and should be accompanied with decent salary and conditions,” he said.

Like ASSÉ, CUTE also demands that all internships associated with studies be paid. Beauvais-Gentile said he was inspired by doctoral students in psychology who have been on an internship strike for the past two months, and who have won increased bursaries in exchange for their internships.

He said CUTE is currently working on a framework to create “regional coalitions for salaries for all internships, at all levels of education.”

“In this way, we want to bring together student leaders but also women’s committees, affinity groups, mobilization committees and individual activists,” he said.

These student organizers are building coalitions within and between schools, as well as between students and non-student groups. Despite still being in its early stages, the movement against student poverty is gearing up for a long-term struggle.

“We will continue the fight for everybody’s emancipation through control over their own work, be it already recognized as such or not,” Beauvais-Gentile said.

4_600_375_90_s_c1.jpg)

1_600_375_90_s_c1.jpg)