Putting Val d’Or in Context

At a press conference held in Val-d’Or on Friday, four representatives of the Crown’s office confirmed that charges concerning extreme abuse suffered by Indigenous women at the hands of provincial police officers have been dropped.

Last fall, members of the Indigenous community in Val-d’Or accused police of engaging in large-scale harassment and intimidation. Women accused police of rape and sexual assault. Radio-Canada’s investigative program Enqûete brought the allegations to the public—inciting outrage and backlash from police officers, many of whom who wore bracelets in a show of solidarity for their accused comrades.

Now, over a long and difficult year later, the Crown’s office has stated that insufficient evidence prevented them from processing charges. The suspended officers will soon return to work and other stories will flood our national news coverage.

But this story does not—and cannot—end here. Narratives that circulate in the mainstream media often start and end in the middle—and this is no exception. But in order to understand even a fraction of the impact of the decision to drop charges, we must look back at our historical colonial realities and relationships.

We must contextualize why Indigenous women are some of the most vulnerable and marginalized people in the country—and how that reality played a role in the announcement Friday.

Although I dare not share stories that are not mine to tell, I do know that there are damaged relationships between settlers and Indigenous peoples that live in the so-called province of Quebec. According to a 2006 Statistics Canada report, people who identified as Aboriginal made up about six per cent of the population in Val-d’Or. The report also noted that there were higher unemployment rates, lower wages and poorer living conditions for Indigenous peoples.

Sometimes, the density of historical facts can be overwhelming, especially since so little of it is covered in our national history books. But there are general conceptions that must penetrate common Canadian consciousness if we are ever going to try and find a mutual word for truth and a peaceful way of moving towards reconciliation. The reality of Canada being a colonial state—both historically and presently—is one of them.

The legal and authoritative systems in place to protect and serve settlers in this country rarely benefit Indigenous peoples. Treaties, acts and laws were imposed in order to displace and control native people’s bodies, land, and territories—often through calculated and violent measures.

Many Indigenous communities have been forced to surrender traditions and adapt their unique systems of governance to the one-size-fits-all model in the Indian Act, all while the Canadian state claims to value and uphold diversity and multiculturalism.

The residential school system—whose last establishment closed in 1996—stole children from their families, homes and territories. They were meant to, as Richard Henry Pratt would say, “kill the Indian… and save the man.” (Pratt was the founder of the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Pennsylvania whose purpose was also forced assimilation.)

At residential schools, administrators cut off children’s literal hair and cut out their figurative tongues. Stories offered by survivors speak about violence, sexual assault and dehumanizing treatment at the hands of priests, nuns and well-meaning settlers who saw Indigenous ways of relating to the world as savage and uncivilized.

Alongside the residential school system was the famous Sixties Scoop that involved Canadian social services and the child welfare system taking native children from their homes and communities to place them with white families. Many survivors today speak about the pain of losing connection to their culture, kin and identity.

Native peoples continue to honour traditional ways of relating to one another through diverse forms of kinship and family structures. These traditional relationships are still punished by social services and a child welfare system that treats relationships outside of the heteronormative nuclear family as deviant. Children continue to be taken from their mothers, aunties and communities, which is why nearly half of all children in foster care in Canada are Indigenous.

These historical realities are a way for us to contextualize the events in Val-d’Or and situate ourselves in a better place to understand the present. But the past can only be examined for so long. We need to look forward and ask how this decision will affect relationships between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people—especially as Canada’s government, media outlets and academic institutions insist on reciting the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s calls to action like a national anthem.

Native women are not vulnerable because they are weak—on the contrary, women have been essential to the survival, revival and wellbeing of their nations. But what are we supposed to think when so many have gone missing, have been murdered or have taken their own lives? What are the women in Val-d’Or supposed to think when they share their stories despite great risk, only to be rejected or sent home without solutions?

I spoke with a representative from the Native Friendship Centre of Val-d’Or who wished to remain anonymous. “Who’s going to protect us?” she asked, through a strained voice. “There’s nobody there to protect us.”

She spoke about how it’s not only the most vulnerable women—those who have been prostituted or suffer from drug and alcohol addiction—who are in danger. “I fear for my daughter,” she said, who goes to school and is a “good girl,” but who may one day “get a flat tire or need help, and then who does she call?”

Decisions like the one on Friday continue to undermine any potential for healing. We must examine how the Canadian law—and those positioned to enforce it—do not “protect and serve” everyone.

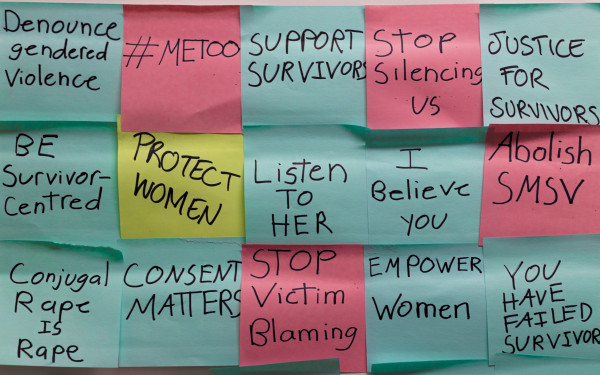

Now is the time that native women in Val-d’Or and across the country need the support and solidarity of their allies.

On Tuesday, there is a vigil for Indigenous women at Place des Arts. But I’m sick of vigils. I don’t want to cry and beat the drum for our stolen sisters anymore. I want to see systems of governance that offer justice for all peoples on this land and traditional practices and protocol upheld and valued. Otherwise, there will never be a relationship of respect and reciprocity, and the Canadian state will continue to colonize first and apologize later.

RETRACTION: The Link would like to acknowledge the insensitive graphic published with the “Putting Val d’Or in Context” article in the opinions section of Volume 37, Issue 13. The graphic depicted two police officers brutalizing an Indigenous woman with the word “Savages” written underneath. It was unnecessarily triggering and shocking, and didn’t accurately capture the article’s content. The Link regrets the error and has retracted the image. It can still be found in our archives. For more questions, email editor@thelinknewspaper.ca