Filipino history lessons taught through food

How the Philippines’ different colonial periods impacted its cuisine

Filipino cuisine bears undeniable similarities to the cooking styles of its neighbouring countries, and that’s not by accident. Look to the Philippines’ complicated colonial past, and you’ll find the roots to many of the country’s most famous dishes.

A pre-colonial Philippines

Like many Asian countries, rice is the foundation to the Filipino food pyramid. The staple crop was brought over to Cagayan Valley, the north-most point of the Philippines, during an Indo-Malaysian, Chinese, and Vietnamese wave of migration in around 3400 BC.

Over 3000 years later, give or take a few hundred, China began to trade regularly with the Philippines. This introduced soy sauce, fish sauce, and stir-frying to their cooking arsenal. What followed was a beautiful thing—the creation of dishes like pancit, siopao, and lumpia. The Filipino response to chow mein, cha siu bao, and spring rolls.

Pancit is a noodle dish with stir-fried meat and vegetables best eaten in overloaded spoonfuls. The Filipino version of a steamed pork bun, siopao, has the perfect ratio between fluffy bun and sweet pork filling. When it comes to lumpia, nothing can go wrong with a deep fried spring roll.

As the Philippines began to trade with India, Malaysia, and Indonesia, dishes like kare-kare started to emerge as the Filipino interpretation of curry. Kare-kare is a stew with a rich peanut sauce, traditionally made with oxtail.

This all happened before Spain ever set foot in the Philippines—yet they hold such a vice grip on the country’s palette.

Who are these white men and why can’t I eat with my hands?

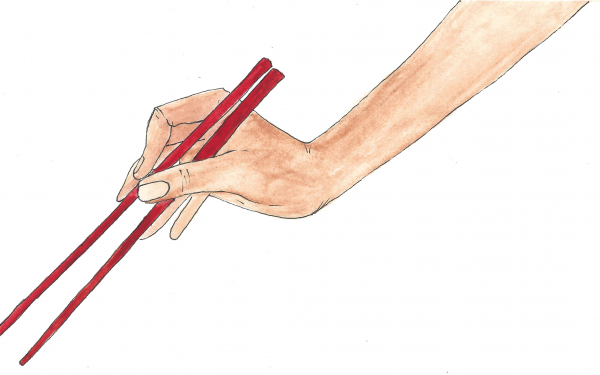

Before Ferdinand Magellan arrived in the Philippines in 1521, it was tradition to eat kamayan style, meaning to eat with your hands, typically with banana leaves as placemats. The Spanish introduced eating with utensils to wean Filipinos away from their supposed "barbarism." The practice was adopted for special occasions, especially when eating with Spaniards.

As time went on, however, using a fork and knife fell out of style. Now you’ll find Filipinos eating with a spoon and fork—it’s simply more practical. If you disagree, go eat rice with a fork and knife and report back with how efficient that was.

While the colonizer’s method of eating didn’t last, their culinary influence did. Some food historians claim that 80 per cent of Filipino dishes have Spanish roots. Because the colonizers were the upper echelon of society, many dishes adapted by upper-class Filipinos also took inspiration from the Spanish.

The origin story behind one of the most iconic Filipino foods is unclear, but some believe it was a mix of existing tradition and Spanish flavour that created lechon as we know it today.

Sitting at the head of the table on a massive dish lined with countless layers of aluminum foil, lechon is a whole roasted pig known for its juicy meat and crispy golden brown skin. It’s essential to any family gathering.

A dish scarcely found on buffet tables but always in a nondescript container in the fridge, is adobo. Something about adobo just reminds me of a Wednesday evening at home—it’s nothing crazy, but it’s always nice. Adobo is usually chicken marinated in vinegar, soy sauce, and spices—but there’s no rules against other proteins. Pre-colonial Filipinos had no qualms against fish, meat, or veggies cooked adobo style. In fact, marinating the food in vinegar was a way to preserve it.

When the Spanish saw this traditional way of cooking, they decided to slap a Spanish name on it and call it a day.

Their nearly 400 year-long colonization of the Philippines also left behind some honourable mentions like chicharon (fried pork rinds), leche flan (caramel custard), and empanadas.

Who are these white men and why do they all have a God complex?

A revolt was brewing, and the kettle boiled over in 1896 in the shape of the Philippine Revolution. The revolution ended in 1898, when Spain passed their control of the Philippines over to the Americans. The Philippines would only gain independence in 1946.

Besides Westernizing the education system, making English the official language of business, and turning the Philippines’ top export into its people, the American occupation created one of my favourite things to order at the Filipino fast food chain Jollibee—Filipino spaghetti.

As the Americans dug their feet into Philippine soil, they brought canned goods like tomato ketchup with them. During the Second World War, tomato ketchup was hard to come by. Tomatoes didn’t grow well in the Philippines, so changes needed to be made to satisfy the ketchup craving. Looking to the heavens for answers, they saw plentiful banana trees—a fruit that thrives in the humid weather.

María Orosa, a food technologist, connected the dots and invented banana ketchup.

Pair the sweetness of the banana ketchup with the savouriness of spaghetti and you get the beginnings of a contemporary Filipino staple. If you don’t have banana ketchup in the pantry, you can hit the right flavour profile by adding sugar to your meat sauce. So cook up some hot dogs, noodles, and sauce, and lament the absence of a Jollibee in Montreal.

Why would you occupy us? We made dessert together

Before Japan utterly ransacked the Philippines during WWII, the two countries made nice and traded with each other.

Based on the Japanese kakigori, a dessert comprised of shaved ice and sweet beans, the Filipino remix took off in the 1900s when ice and refrigeration became more readily available. The earliest versions featured cooked red beans or mung beans in crushed ice with sugar and milk, but as more native ingredients were added we got to how halo-halo is made today.

Halo-halo translates to “mix-mix,” which tells you everything you need to know. The dessert contains a multitude of ingredients, and it changes depending on the region. Most commonly, it’s made with crushed ice, evaporated milk, purple sweet potato, sweetened beans, coconut strips, palm stems, gelatin, boiled taro, flan (colonial crossover!), and a scoop of ice cream.

It doesn’t sound like those components would work well together, but they do.

While the Philippines’ colonial history is the root to many of the country’s problems today, it’s worth remembering that life goes on. Life went on for our ancestors, and we still eat like them today. Their traditions endured, even after three different foreign powers claiming rule over the country. Filipinos took the colonial influences, added some local seasoning, and re-appropriated them into something amazing. So pull out a spoon and fork, and let’s celebrate our history.

This article originally appeared in The Food Issue, published November 3, 2020.