One river, two canoes, three borders, and the U.S. election

Why the Akwesasne Mohawk Nation fears for their community and the U.S. election’s consequences

“I believe in the Great Law [of Peace], but at the same time I’m not delusional to think that it doesn’t count, that whatever the United States or Canada does doesn’t bother us. It does. It affects us deeply. This year I voted,” said Margie Skidders, a member of the Akwesasne Mohawk Nation and co-editor at Indian Time, a weekly newspaper that covers news in Akwesasne and their sister Iroquois communities.

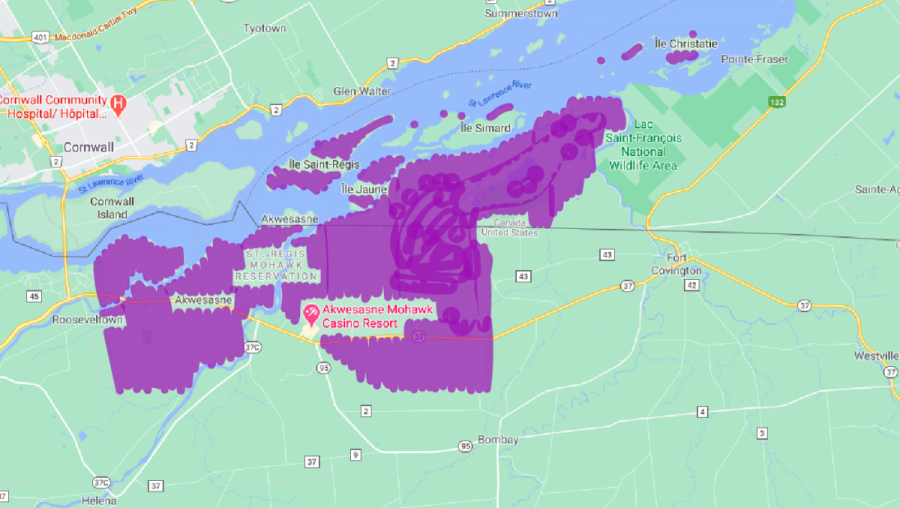

The American and Canadian border cuts straight through Skidders’ territory, complicating life for her and fellow community members. “Living here, being divided by two countries, one state and two provinces,” said Skidders. “We’ve learned to deal with a lot.”

The U.S. election only amplifies the liminal and complex territorial and political position of the Akwesasne. Skidders said community members are divided on whether or not to vote.

“A number of people will not vote in the election on the belief that U.S. elections are not part of our entire makeup, our society, our laws or the Great Law.”

The Great Law of Peace is the founding constitution of the Iroquois confederacy, which recognizes the five Haudenosaunee nations—including the Mohawk—as independent from settler nations. The Two Row Wampum Treaty of 1613 was the basis for this constitution. A wampum belt made of white and purple shells was used to record and symbolize the treaty that “shall be binding forever as long as Mother Earth is still in motion,” as is said in the oral tradition of the Haudenosaunee.

The belt has two purple lines running parallel end to end. One line represents the Haudenosaunee, and the other represents settlers. They’re on separate courses down the same river, bound to an agreement to coexist peacefully without interfering with one another.

“The U.S. is in a different canoe than ours,” said Skidders. “They are in their canoe, and we are in another canoe.”

“Living here, being divided by two countries, one state and two provinces. We’ve learned to deal with a lot.” —Margie Skidders

In a present-day context, this means the Mohawk nation is separate from the U.S. and Canadian governments, along with their laws, borders, and elections. While the Akwesasne nation should, legally, be in total control over their lands and laws, this is not the reality. The U.S. election affects the Akwesasne profoundly, said Skidders, “from the air to the water to everything. Every element of our life is affected.”

Skidders thinks it’d be very difficult to find a person in Akwesasne who supports Donald Trump, despite being surrounded by the politically conservative rural areas of upper New York state and southern Ontario and Quebec.

“He’s a dangerous person to the planet, to the very social fabric of our society. He’s a danger,” said Skidders.

During his term, President Trump reversed 70 environmental rules and regulations directly affecting the Akwesasne’s environmental protection initiatives. Decades of industrial pollution —on both sides of the border from corporations such as General Motors—has left their waters with high levels of toxins that continue to have severe health consequences in the community and disrupt their traditional ways of living.

“If I had to choose one thing that is Akwesasne, it would be our waters. It would be the St. Lawrence river, the St. Regis river, the Raquette river. That’s the soul of us, I think,” said Skidders.

Final election results will only be known weeks from now because of the ongoing counting of mail-in ballots. While Skidders waits for the final count, her fears extend beyond her territory and the issues facing her nation. She’s worried about American immigration policies and the wall on the southern U.S. border.

“Those are our cousins from the South,” said Skidders. “They’re part of us; to see them separated ripped at our heart. Those are our people.”

Skidders has reservations about Biden, but she thinks he’s a step in the right direction.