Montreal’s Durocher Art Space At Risk

How Gentrification Is Threatening the Infamous Art Studio

It’s not unusual to find Baltimore Loth hard at work in his art studio until dawn. Whether he’s drawing, painting, or getting his hands dirty sculpting, the spacious loft at the corner of Beaubien St. and Durocher St. is his playground, and represents much more to the local artistic community.

The undergraduate studio art student at Concordia University splits the studio with his brother Arthur, and a couple of their art-enthusiastic friends such as Bérénice Galarneau and Alex Guay.

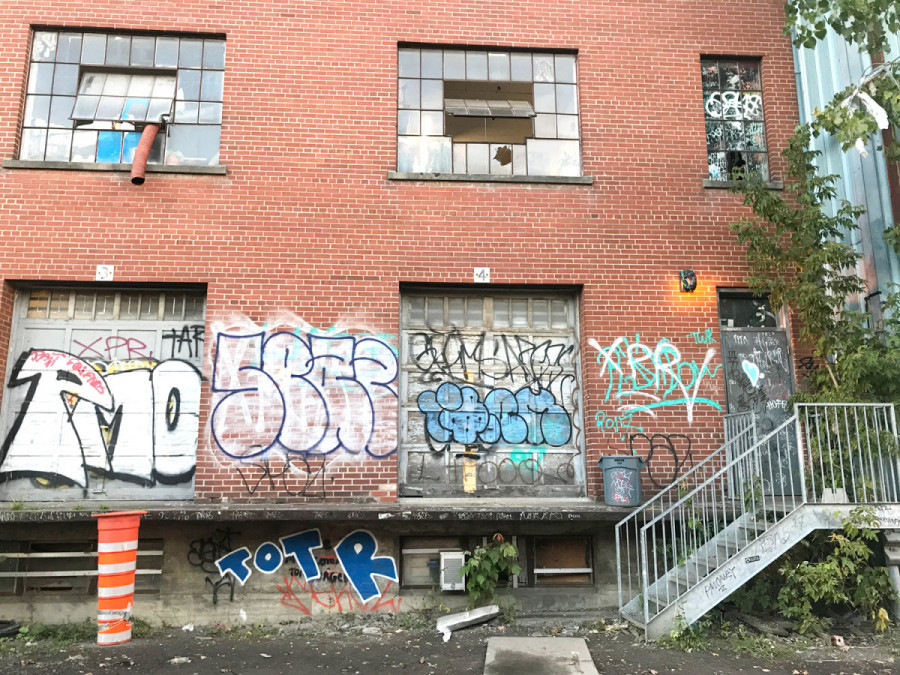

Commonly referred to as “the studio” or “Durocher,” the second-floor space was turned into an art studio by its current tenants. Illuminated through factory-style windows, the space offers work stations for various forms of art, as well as a skateboard ramp.

What makes this space so special, besides being a pretty damn cool studio, is its versatility. The tenants regularly rent it out to other creatives as a cheap location for whatever they may need: art exhibitions, fashion shows, musical performances, magazine launches, premieres, after-hours parties, you name it.

“It’s really good for the music scene,” said Guay in French. “A lot of DJs crave playing here. It’s happened that we didn’t pay DJs who just wanted to play because they love the vibe.”

Unlike any other in the city, the spot has gained a reputation for offering a vibrant and judgement-free environment that fosters creativity and self-expression. For many, heading to Durocher after the bar is part of this city’s nightlife.

The building’s dingy studios, which also hosted iconic Moonshine all-nighter parties, have become a staple for Montreal’s artistic and after-hours scene. It is where all kinds of creatives come together to showcase their art, meet like-minded people and have a good time.

This is where it gets uninspiring. The Loth brothers recall their conversation with a woman who came to look at an empty site right across from the Durocher building. They asked her what was being built.

“A building with eight floors,” they recalled her saying. The brothers quickly turned around to count that their building had only four floors. The construction would completely block all the studio’s sunlight. “Yup…the bigger, the better,” they reported her saying.

Developments in the Mile-Ex have and continue to affect these central communities. Skyrocketing rents and commercial projects have forced many artists in the neighbourhood to pack up their paint brushes and leave their workshops on a quest to find affordable studios.

The area is in full transformation, and recently attracted artificial intelligence companies. At Durocher, rumour has it most leases will not be renewed.

“That is what we have here. Something authentic.” — Baltimore Loth

According to tenants, property manager Benjamin Silver refuses to renew leases for longer than two years and won’t reveal any information on the future plans for the building. Silver has not responded to offer a comment.

“I would be very upset to be forced out from here,” said Galarneau in French, “but I would feel worse about the building being demolished.”

What the artists are defending is the space’s functionality within the community, and the building should be recognized and preserved as cultural heritage.

It provides an environment that fosters creativity, gathers different communities, sparks inspirational conversations, and is where Montreal’s creative underground culture thrives.

“If you look at Berlin, there are some really grunge and super weird places. Those spots are touristic and sought after because it’s authentic,” said Baltimore in French. “That is what we have here. Something authentic.”

RelatedSince 2007, Ateliers créatifs Montréal, a non-profit real estate developer, has been working towards developing and protecting affordable, adequate and sustainable work and creative spaces for artists.

ACM general director Gilles Renaud said in French that “what is happening at the corner of Beaubien and Durocher is the perfect example of an interesting phenomenon we call ‘the pleasant owner.’”

He explained that when a private owner has had a building for a significant amount of time, they will often avoid costly investments and keep it in a bad state, while the land’s value increases.

While these conditions give artists access to affordable spaces, Renaud described them as misleading. “One day, [the owner] will sell it for three times the price value, or receive an offer they cannot refuse.”

Renaud believes in the importance of economic development in neighbourhoods, but that it should cohabit with the artists.

Galarneau, Guay, the Loth brothers, and other occupants in the building have denounced the landlord’s inaction when it comes to issues with the infrastructure.

The city and province recognize the issue. Quebec is investing $25 million over five years to fund renovations and development of workspaces for artists, revitalize neighbourhoods and encourage collective ownership of workshops.

The Ministry of Culture and Communications and a $147,000 cheque may help ACM preserve 305 Bellechasse, a large building with about 150 artists that would face skyrocketing rent, but negotiations with the building’s owners are still ongoing.

Durocher’s future seems less optimistic. There are two reasons behind ACM’s reluctance of preserving the building.

Renaud explained that the infrastructure’s extremely deteriorated state needs expensive renovations. Those high costs wouldn’t be justified because of the building’s small size, compared to locations such as 305 Bellechasse St. He added that ACM focuses on bigger buildings to optimize their investments, and benefit a maximum number of artists at a time.

For now, Durocher’s future remains unclear.

This article has been updated to better reflect the reality of the situation.