Medicalization, Privatization and Stigmatization

Feminist Critiques of Health Care Shift the Conversation from Physiology to Sociology

404 not found.

That is about all that’s left of the Women’s Health Contribution Program and the services that relied on its funding. The Government of Canada, under Conservative Prime Minister Stephen Harper, cut the Health Canada subsidiary four years ago.

A couple clicks through the Health Canada website will bring you to a statement from September 2012, declaring “funding for the Women’s Health Contribution Program, a non-service delivery program which was established at a time when there were not many programs aimed towards women’s health, will be eliminated.”

This elimination, which was expected to save the government $2.85 million a year, hastened the downward spiral for access to women’s health care in Canada.

“It’s a sad situation,” said Dr. Geneviève Rail, a professor from Concordia University’s Simone de Beauvoir Institute. Her teaching, she explained, partly focuses on feminist perspectives of health care. “Women’s health in Canada was much better organized 30 years ago than it is today.”

The elimination of funding for the WHCP lead to the dissolution of the Canadian Women’s Health Network, which had previously supported more than 70 organizations across the country for over 20 years. They closed their doors in November 2014 because they couldn’t find alternate funding.

“I think access [to health care] has been hampered, and is hampered more and more, as we continue to divest from public health and privatize our health care system,” said Rail.

In a statement, the CWHN’s Board of Directors issued its own concerns for the state of women’s health care funding in Canada.

The funding and research which remains, Rail said, is dangerously one-sided—particularly in terms of mental health. A lot of it, she said, focuses on the physiology of mental illness. This includes the study of how brain chemistry affects behavior.

“They aren’t funding research into other directions,” she said, and the research happening doesn’t take other approaches to healing women.

The feminist perspective, Rail explained, encompasses everyone, regardless of whether they identify as male, female, or non-binary. It looks at mental health through the two main lenses of social causation and social construction.

“Instead of looking at issues of mental illness as caused by some psychological or physiological defect, [researchers] see the causation of mental illness mostly as part of social factors,” she explained of the former. “We’ll show how these social factors are working to basically render women ill.”

Feminist study insists that the root cause for mental illness lies outside of the individual. “ ere’s a number of things that don’t go so well for women,” Rail said. “They are in financial, social, or psychological situations that aren’t as advantageous as their male counterparts’.”

“It’s a sad situation. Women’s health in Canada was much better organized 30 years ago than it is today.” – Dr. Geneviève Rail

Social construction, on the other hand, is all about the interpretation of behaviors. “In this branch, feminist researchers come to deconstruct the ways in which we medicate women, and we construct particular ways of being as signs of mental illness,” Rail said. “We could construct them in other ways, and find that women acting in particular ways are actually rational and sane, and not ill.”

Gabrielle Bouchard, peer support and trans advocacy coordinator at the Centre for Gender Advocacy, agreed that stigmas associated with gender contribute to the proliferation of mental illness. As a result, if you identify as anything other than a cis-male, Bouchard said, you’re at an elevated risk for mental illness. “Gender is an important thing,” she said. “Unless you’re in a position of privilege and you have a space where you could be non-gendered, you have to face genderization, like it or not, all the fucking time.”

The issue, she explained, trickles into how gender is appropriated by researchers, misinterpreted, and integrated into studies of mental health.

Health Canada’s Institute for Gender and Health includes a section on its website which explains how “every cell is sexed, and every person is gendered.” Its descriptions of sex and gender, which highlight the biological and social differences between the two, also touch on their perceived interconnectedness. “If you look at what they’re saying about their definition of sex and their definition of gender, they’re actually pretty good,” Bouchard stated. “They’re not bad definitions.”

What is problematic, she said, is the way these concepts are interwoven into health research. Categorizing people by their biological sex furthers the notion that sex and gender are intrinsically important to study.

For example, she cited that the function of a uterus is not the same for someone of childbearing age as it is for someone who has gone through menopause, nor as it is for an individual taking testosterone supplements. For that reason, using biological sex as a reason for devaluing one’s gender is, as Bouchard said, fucked.

“I think we overestimate the necessity for gender,” Bouchard said. “It’s like if we say it’s very important to have somebody’s gender on their resume. It’s not relevant, but it has an impact.”

The impact, she explained, falls back into the social perception of gender-associated attributes, and the way in which it puts some at an advantage, and others at a disadvantage.

In the prevailing pharmaceutical approach to mental illness, chemical imbalances are seen as the main villain and prescription drugs as the knight-in-shining- armour. But that’s a band-aid solution, explained Rail. Drugs treat the problem without addressing its cause.

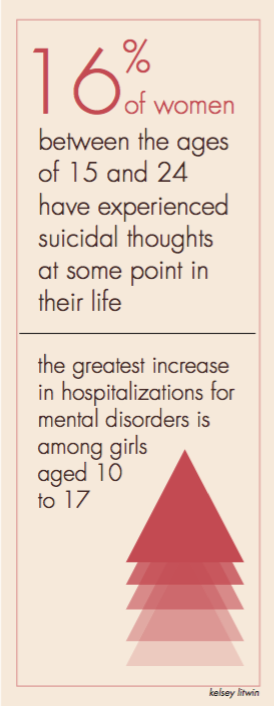

A 2016 report from Statistics Canada on “the health of girls and women in Canada” found that antidepressants were the most common medication prescribed to women between the ages of 15 to 24 in Canada, second only to hormonal contraceptives.

Rail explained that it’s the combination of the pharmaceutical industry’s strength, the success of its marketing, and the social construction of mental illness that leads to this overmedication of women.

“It is difficult, and it’s becoming more and more difficult […] in a very intersectional way as well,” she explained. “If you’re a woman of colour, if you’re an immigrant woman, if you’re a poor woman, already the doctor-patient relationships are not easy, as far as mental health is concerned.”

Rail said that Canada’s Indigenous population is particularly at risk. “Here is a very strong link with social factors, and after hundreds of years of marginalization, discrimination, oppression, exploitation,” she said, “there are acute problems in some of the [Indigenous] communities. Unfortunately, our system is not set up at all to accommodate for that.”

The way in which Canada studies and treats mental illness, she explained, just reinforces gender- associated stigmas.

“In the end, it’s the social status quo. We’re not changing what is bad. We’re keeping it the same, and that is a big problem.”

1_600_375_90_s_c1.jpg)

ED1(WEB)_600_375_90_s_c1.jpg)