Martin Shkreli: Bad Egg in a Rotten World

Famed Asshole Shkreli Is Just Another Monster in a Post-Industrialized Capitalist World

At this point, we all know his name. Martin Shkreli, the former hedge fund manager who forced his way into our lives when he raised the price of a drug used to treat toxoplasmosis, an opportunistic parasitic disease associated with HIV.

Of course, this immediately raised the hackles of pretty much everyone who heard about it, only to be furthered when Shkreli chose to really lock-up the Asshole of the Year award by personally insulting every single opponent to step to him on Twitter.

Now, weeks later, we know pretty much all there is to know about Martin Shkreli. We know where he lives, we know his phone number, we know the inordinate amount of money he spends on playboy bullshit, like 50-year-old champagne and helicopter rides. We know what his OkCupid profile looks like, that he loves pop-punk and that he bought Kurt Cobain’s credit card.

We’ve heard his slimy voice, declaring the price hike “reasonable,” and we’ve seen his slimy face twist into a slimy rich-person smile on live TV. We know he once offered $10,000 to his ex for sexual favours. We watched him offer Bernie Sanders a paltry bribe, get rejected (Sanders called him the “poster boy for drug company greed”), and then throw a tantrum on Fox News. So, we all definitely have a pretty clear image of the monster/asshole/general dick that is Martin Shkreli. But, to be honest, I think we’ve somehow missed the point.

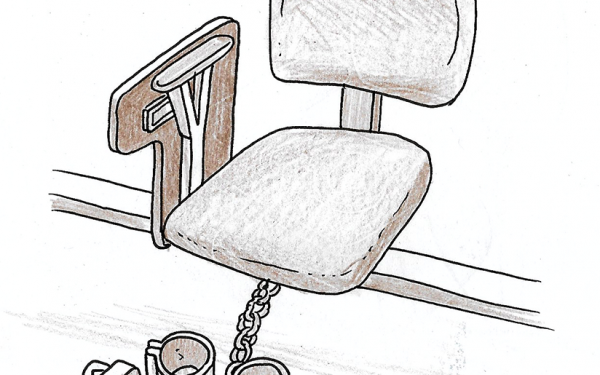

The point of Shkreli should not be that he is a monster, a singular bad egg in the otherwise delicious egg salad of capitalism. The point of Shkreli should be a terrifying, end-of-a-horror-movie type realization about who prospers in the system we’ve built for ourselves, and who gets the short end of the metaphorical stick literally every time.

So let’s shift the conversation away from Shkreli-as-individual, and towards a conversation on Shkreli-as-allegory. Not that bullshit allegory, penned by political pundits and underdeveloped manchild-ren like Trump, or any of that “by-the-bootstraps” garbage first spouted by the sociopathic robber-barons of early America. No, instead, let’s talk about the system that allowed and encouraged the rise of a man like Shkreli, and how fucked up it is that it’s even in place, because this happens all the time.

Easy example: Valeant Pharmaceuticals International, a colossal, multi-national pharmaceutical conglomerate based in Laval. Over the last year Valeant has become the posterchild for illicit pharma stratagems as the current subject of two separate U.S. investigations into allegedly nefarious drug pricing practices. Just to name one case in a string of patent-purchases, back in April, Valeant bought Nitropress and Isuprel, two life-saving heart medications, and promptly raised the price of each.

These are just two drugs acquired in one deal, which also included an additional package of four other drug patents. One deal, orchestrated by a spider web of pharmaceutical corporations who are operating under a mandate that purchasing drug patents and jacking up prices is always a better investment than research and development (a whopping 3 per cent of the company’s income last year was spent on R&D). Valeant reported $111.6 billion in 2014 revenues.

Outcry resulted. The company was subpoenaed with a list of 22 questions regarding the hikes, which were ignored, leading to multiple U.S. senators denouncing the company’s practices. Valeant stocks have plummeted, but even the bankruptcy of Canada’s largest pharmaceutical company would have little impact in the grand scheme of the industry.

.png)

“Valeant is using precisely the same business model as Martin Shkreli,” the senators who served the subpoena stated.

Now, when Shkreli is synonymous with the evils of big pharma, and small-time drugmaker Imprimis Pharmaceuticals has just offered a new version of Daraprim (Shkreli’s recently patented drug) for $1 a pill, where do we stand? Imprimis is a compounding pharmacy, which means that it can only offer prescriptions at a doctor’s request, on a one-to-one basis, instead of en masse.

What’s more, due to copyright laws, it’s unable to offer an exact copy of Daraprim. Conversely, companies like Valeant, or Turing Pharmaceuticals (Shkreli’s company), make their drugs available through specialty pharmacies, who lobby insurers to pay for it, making the entire process of accessing a drug much easier for doctors and patients than anything a compounding pharmaceutical company can offer.

This industry is cyclical and incestuous. Since 1990, the concentration of wealth in the pharmaceutical share has condensed—the top 10 big pharma names accounting for 46 per cent of the sector in 2002, a rise from 28 per cent in 1990. It’s profitable and sustainable to purchase patents, jack prices and buy up territory. Drugs are treated as commodities in the fluctuating market, pieces to be played on a global chessboard, and current-day approval standards from the FDA and other regulators encourage the purchase of big name drugs from specialty pharmacies, as opposed to small-time compounding pharmacies.

With a pharmaceutical sector this backhanded and corrupt, who else but someone like Martin Shkreli would prosper? Who else would even enter the field?