Making, Cleaning, Collaborating

Three Concordia Artists Share Their Approach to a Sustainable Practice

When we talk about sustainability, we use terms like “going green” and “eco-friendly.” We think of our physical planet and the people on it. In private, these conversations are a lot different.

It’s more complex than a headline. People are very anxious and think deeply about this issue. It’s easier to get angry and harder to go through the intricacy of it all, but when we do, it usually comes down to is this: Are we trying to save the planet or trying to save ourselves?

Artists have to have a lot of conversations like these. We’re trained to question everything and to be responsible for what we make, and sometimes it’s tough to take ownership if you don’t know why you’ve made it in the first place. In that case, we have to ask—should this even exist?

We’re still learning how to be sustainable artists. In some ways, creation is directly tied to the environment, like materials and their effects on our bodies. In other ways, creation relates to our mental health, our drive to create, our curiosity, our ability to make a living, and our collaboration with other artists. What I learned through conversations with three sustainable artists, all in different stages of their careers, is that all these things are very closely connected.

Making

Mindy Yan Miller is a long-time fibres and material practices professor at Concordia. She teaches various courses dealing with textiles, fabric, and felt.

Miller and her husband had a small textile business after she graduated from the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design. “I guess I wanted to be a craftsperson more than an artist,” she said. “I wanted to make things people would use.”

Miller soon became aware that her business was more about production than the art of making.

She became frustrated with the production side of the business. Since her goal was to sell affordable clothing, she needed to keep costs low and work fast. “We weren’t making high art or high craft, more trying to make things that went into women’s clothing stores,” she said.

At that point for Miller, it was time to question the act of making. She knew that what she was making was useful but knew these already existed in other forms.

In 1990, Miller began her professional art practice, a large part of which revolves around used clothing. She managed to collect used clothing in bulk from places like Salvation Army and Value Village. She said she would have thousands of garments filling up her studio. “Even then they had a real excess,” recalled Miller.

“It created a performative practice because for the next two years, I was just dealing with this huge mound of clothing,” she said.

The clothing has been used in Miller’s work—crammed in attic walls, stacked high in a glass display case, and folded on the ground in the shape of an American flag. Miller’s other projects include recycling Coke cans and running a “mending booth,” where artists offer to repair clothing for free.

In one of her classes, Miller discusses the relationship of making in regard to the land and local culture.

Another thing Miller discusses in her class is the mentality student artists have in this capitalist era. “The students are so anxious all the time,” she said. “[I try] to remind people it wasn’t always like that.”

“You kind of have to accept to stop looking for doing new all the time […] If someone already did the best idea, you kind of have to redo it.” —_Joé Côté-Rancourt_

According to Miller, artists are resisting capitalism and the way it makes us feel. “They want to return to making,” she said. “I’ve had some people who will make all their own clothes.”

Miller mentioned a student by the name of Johanna Autin, who, as a part of her practice, went to work on a farm. Instead of buying wool for felting, Autin actually helped to shear the sheep to learn about the process their materials were going through.

Miller is still consciously digesting the workings of modern structures—focusing on production and labour, people, and what we do in our lives.

Cleaning

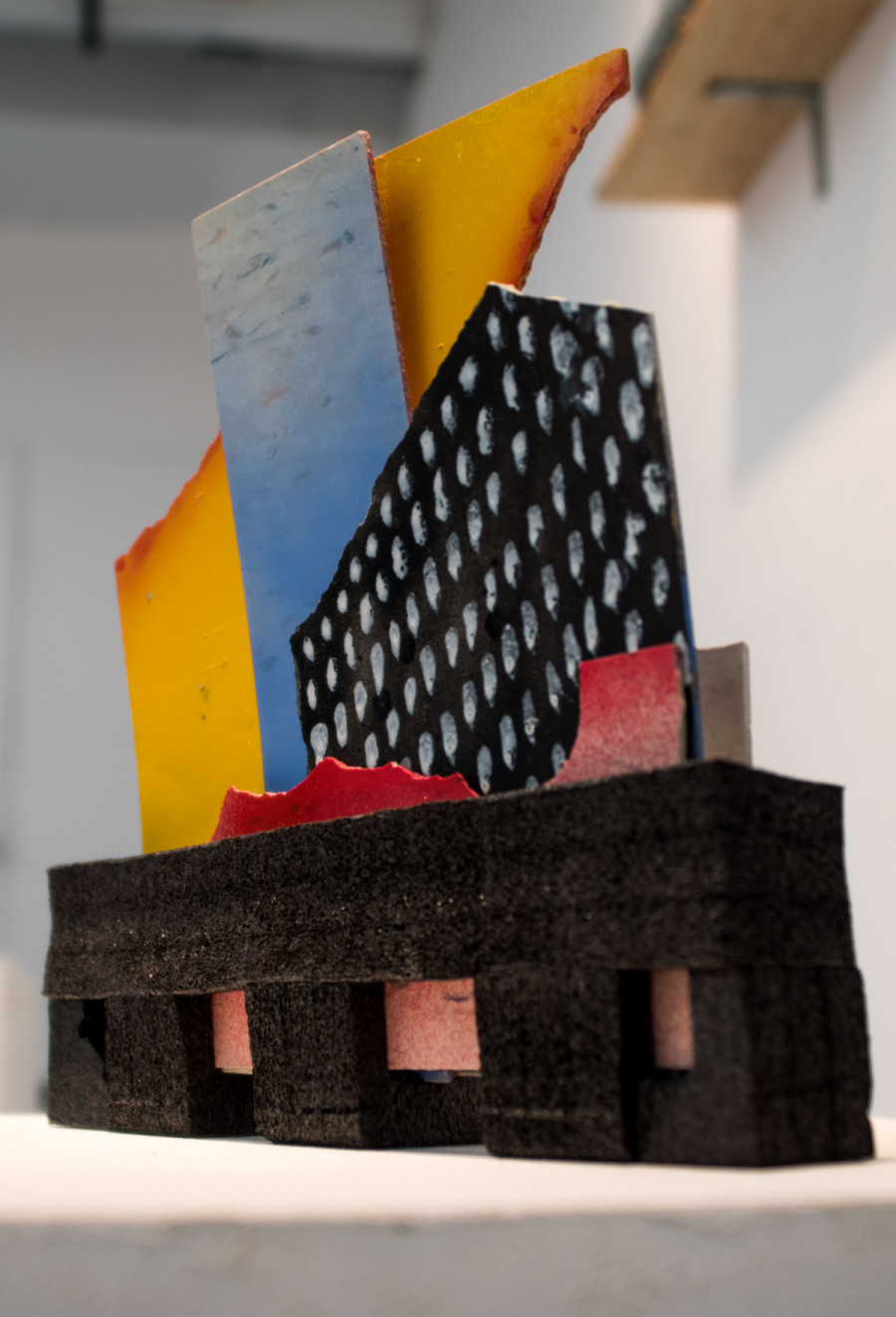

Joé Côté-Rancourt is a sculpture student whose current practice is centred around sustainability—or, more specifically, cleaning. Côté-Rancourt is a hospital janitor by night and makes a habit of collecting trash that might be useful. This includes tools, hospital equipment, cardboard, and styrofoam, which he reuses in his work.

His independent study with Professor Kelly Jazvac follows the same principle. Right now, Côté-Rancourt’s main influence comes from the work of American 1970s artist Mierle Laderman Ukeles, whose manifesto amplified the role of museum maintenance workers and put them on the same level as museum curators.

Côté-Rancourt said that in our minds, “the best janitor would be a janitor we never encounter, that would just be like a ghost in the space, and everything would be clean.”

For his study, Côté-Rancourt has taken on the janitorial role at Concordia’s Visual Arts building. Concordia University’s Centre for Creative Reuse has already set up bins around the building to collect reusable materials, and Côté-Rancourt uses a lot of these in his work, along with materials he finds himself. This includes tiles for landscapes, used erasers, and mop buckets.

He also made a set of chairs made from tires bolted together, which, weather permitting, are on display outside of the Visual Arts building for the rest of the year.

Côté-Rancourt said he also sees reusing ideas as an important part of a sustainable practice. “You kind of have to accept to stop looking for doing new all the time. That’s something we really are pushed into in arts, to do the ‘new’ thing, or that ‘different’ thing,” he said. “If someone already did the best idea, you kind of have to redo it. Because if it’s the best idea, and not everybody is doing it, you have to promote the best idea.”

Côté-Rancourt said that as long as the artist is tweaking the approach or is able to present the idea as belonging to someone else, people should be able to incorporate others’ ideas in their work. “That’s something that kind of helped me reduce a lot of stress of creation and always [trying to be] about that new thing.”

He is one of the students who restarted the association for undergraduate sculpture students last year, which helps students share materials, brainstorm, and organize shows.

Collaborating

Sustainability in art can go beyond a work’s environmental impact. Working collaboratively can provide artists with the financial and mental foundation necessary to maintain a healthy creative process and ensure they can continue their work in the long term.

Elise Simard is a Montreal-based animator and professor of animation at Concordia. She now works with a collective called Astroplastique. Its members rent a studio space together in the southwest of Montreal, working collaboratively on contract work and sharing supplies, equipment, and even drawings.

Simard said the collective came together to deal with several problems facing animators, such as having less money for projects, not knowing if an independent project can be financed, and the mental toll of working alone.

“One of the first things that I noticed is that competition was very counterproductive,” she said. “It just didn’t feel like it was a good frame of mind for the time because people are withering away. And it feels like it should be the opposite. We should be collaborating and not competing among each other.” It can also help to be part of a group that deals with clients rather than doing so alone.

Communication is an important way to stabilize the client-artist relationship. “How can we be transparent with who we work with,” she asked, “so they have a better idea of our reality, and hopefully be on our side throughout this process instead of having people manipulating other people into delivering them something?”

Simard also talked about the importance of being able to choose which projects to accept when doing commercial artwork, and being a part of a group makes it more affordable to say no. “It’s very important who I work for,” Simard said, adding she has refused contracts because they clashed with her personal values.

While she enjoys collaborating, she’s been trying new things like mentoring and managing a team. “I don’t know what I want, but I know I want something else,” she said. “I feel like I need something maybe a little bit more radical and I don’t know what that is. I’m in transition.”

Regardless of her role, art is inseparable from values, and a growing awareness of the importance of sustainability triggers a deeper reflection about what this means.

It is up to individual artists to decide what this looks like in practice. Either way, the material aspects are only one component of the bigger picture, and the intangible is the underpinning of a sustainable practice.