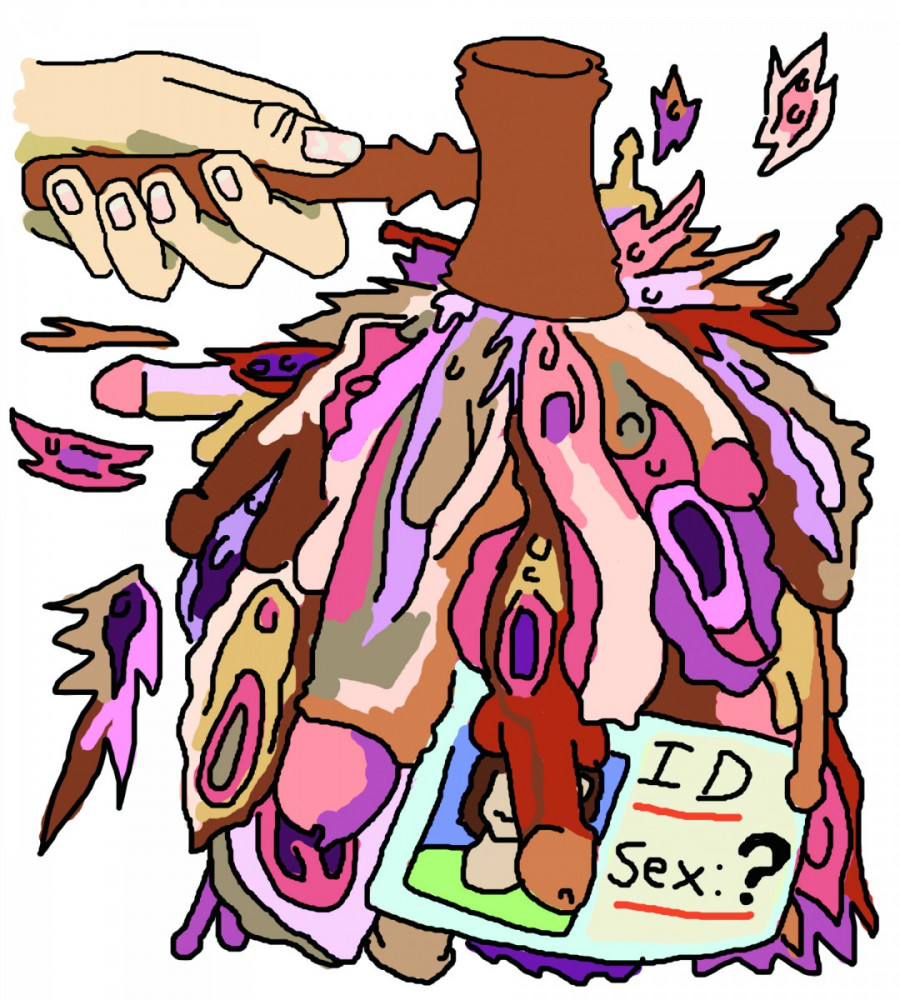

Legislating the Human Body

Centre for Gender Advocacy Contests Backwards Regulation on Changing Gender Marker

“If you want to have your gender marker changed, you’ll have to have your penis cut off.”

This is the sort of voice message trans people receive from government officials during the transition process in Quebec, according to Centre for Gender Advocacy coordinator Gabrielle Bouchard.

Currently, trans people are required to undergo full surgery—a hysterectomy, which removes the uterus, or a vaginoplasty, where the penis is inverted and an artificial vaginal cavity created—before they’re allowed to legally change their gender markers on legal documents.

The law is under review, as many trans activists believe it should be— both required surgeries are dangerous and expensive. But what should constitute an important step forward for Quebec’s trans community may instead force them several decades back.

“The regulation is backwards—it is so 1990s,” said Bouchard, who is suing the government over proposed changes in the legislation. One proposed change would require trans people to go under oath, saying that they will live in the gender they officially identify as until they die.

This is problematic, firstly, because to lie under oath constitutes perjury—an offence which carries up to a 14-year prison sentence—and to even get to the point of swearing the oath, those wishing to officially change their gender marker need a third party to swear that they’ve been living as the gender they identify with for the past two years.

“A lot of trans people, if they declare they meet the criteria and they don’t, they’ll be considered criminals and they’ll be charged. It’s a very strange formulation to say, you must declare, because the criteria are so ambiguous,” Jeansil Bruyere, a McGill law student and trans activist told me.

“[Swearing to be in] the appearance of the gender that you wish to transition into for two years—if you don’t do it for two days, that means that you’re lying under oath, that means that you’re committing perjury, which means your a criminal,” he continued. Bruyere volunteers at a legal clinic, but can’t give legal advice.

Two years can be an eternity, and far from easy, during transition. To be forced to suddenly change your mode of dress before your physical appearance can catch up with your wardrobe at your place of work, with your group of friends and acquaintances, and with your family can be awkward and risky. The requirement would jeopardize trans people’s livelihoods, relationships, and physical well-being.

“When they say ‘must live within the appearance at all times,’ that removes mobility or flexibility for trans people during their transition. You might not necessarily embody your new gender right away—in certain circumstances, say maybe at work, they’re not ready for this,” Bruyere said.

“There are so many factors that are put into play that when you say a trans individual has to live at all times, it really restrains their mobility. They’re not going to be able to do certain things in their day-to-day life.”

To force people who don’t identify with the gender they were assigned at birth to conform to a strictly defined role robs them not only of the flexibility needed to transition smoothly, but also gives faceless bureaucrats the power to enforce gender roles.

“Every feminist in the world should be screaming because of this law. What’s going to be next, the minister of gender? Or police of gender?” Bouchard asks, the rhetorical question dripping with righteous indignation.

“There also is a certain fear and a misunderstanding of gender norms. If you say, ‘in the appearance of the sex to which the designation is requested at all times for at least two years,’ it gives you the idea that you have to look as if, for M-to F, that you’re ‘feminine.’ What does that mean? Can you not have short hair? Does it mean you always have to wear a dress?” Bruyere said.

“Who is going to decide what is dressed in that gender?” he queried. “There is a misunderstanding of the fluidity that gender can encompass.”

Are there any alternatives to this arduous bureaucratic process? Argentina is an interesting example. All they require is a signed affidavit from the person wishing to change their gender.

“I had the chance to shake the hand of a person representing a country that got it right,” Bouchard told me about meeting the consul of Argentina. “It was a good moment for me to be able to shake his hand, and say thank you.”

A correction was made to the article. Gabrielle Bouchard is the coordinator of the Centre for Gender Advocacy, not the director. Also, Jeansil Bruyere is a volunteer and not a coordinator at the trans legal clinic. The Link regrets the error.

_600_375_90_s_c1.jpg)