International Tuition Likely to Skyrocket After Mass Deregulation

By 2019 Quebec Universities Will Have Greenlight to Set Tuition at Whatever They Please

After raising tuition for international students in Engineering, Computer Science and the John Molson School of Business, Concordia President Alan Shepard said the school will be looking to increase tuition for international students in other programs by next year.

Concordia, and other universities in Quebec, don’t have that liberty right now—they have a limit set by the provincial government on how much they can charge international students.

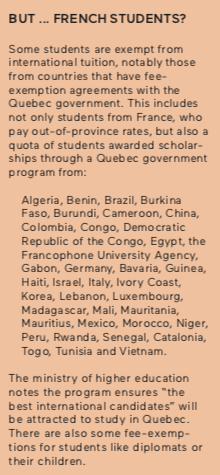

But that will soon change, as the provincial government recently announced the mass deregulation of tuition fees for the majority of international students, with exception to PhD students and those taking thesis-based master’s programs. The changes announced in May will come into effect in the fall of 2019, and mean the already high rates of tuition for international students are likely to skyrocket over the next decade.

***

The mass deregulation follows a trend that began in 2008, when legislative changes allowed Quebec universities to charge international students any amount of tuition, without limit, in six programs: engineering, administration, pure sciences, mathematics, computer science and law.

Anyone who’s lived in Quebec long enough knows any effort to raise the price of tuition can get contentious quickly.

In 2012, the Liberal government tried to raise domestic tuition from $2,168 to $3,793 by 2018. Their efforts were later squashed as student protests and strikes erupted. With half of the student population on strike in April of 2012 and a quarter million students taking part in the protests at their peak the government backed down by September, announcing a freeze in tuition rates. The following Parti Québécois government kept to their promise to not hike tuition, demanding only small increases tied to cost of living.

But tuition increases for international students have never been met with the same backlash.

“They know they can’t do such a vulgar tuition hike to Quebec students,” explained Anas Bouslikhane, the Mobilization Coordinator for the provincial Association for the Voice of Education in Quebec, which represents about 45,000 students across the province.

Tuition hikes for international students have generally happened on a much smaller scale, with small increases that hit students in certain programs, but never all at the same time.

In the five years since 2012, the former finance minister during the 2012 tuition hikes Raymond Bachand has called on the provincial government to deregulate all programs for all international students–through a study he led with the think tank Institut du Québec. The same Institut du Québec study also asked the government to begin a strategic plan to attract and retain more international students, and in 2016 McGill University made the same suggestion in consultation with Quebec’s immigration office. The study also suggested extra funding be awarded to universities that can attract the most.

In 2017 about 25 per cent of all international students remained in Quebec after their degree, and the provincial government has said they hope to see that figure double to strengthen the economy. According to the federal government, international students brought an estimated $1.5 billion into Quebec’s economy and created 14,000 jobs in 2014. But beyond that, the Institut du Québec study stressed that international students in deregulated programs represent a “precious source of income.”

“They know international students don’t have that stability, so they feel like they can do that and get away with it,” Bouslikhane said. “They can come and go and you can charge them whatever you want…It’s that or we’ll find someone else.”

Concordia Student Union General Coordinator Sophie Hough-Martin said the trend towards deregulation stems from an unwillingness by the Liberal government to increase their spending on education.

“It’s a shift towards the privatization of education,” she said. “They’re trying to cut government funding [towards education] and are putting the cost of education on international students instead.”

In 2015 the same government was criticized for their austerity cuts in education, health care and cuts to public sector salaries that were later backed down on. Quebec universities saw a $200 million reduction in funding, leading to staff cuts and a reduction in the number of courses offered.

The Costs

In the 2014-2015 academic year, the number of international students more than doubled in Quebec in comparison to admission rates in the 1999-2000 year. With a total of 42,150 students across Quebec according to Statistics Canada, it equalled a 181 per cent increase. Over the same period, international students saw drastic hikes in their tuition.

In the 1999-2000 school year international undergraduate students taking a full course load of five classes paid between $8,270 and $9,998 in tuition rates per year, and by 2014-2015 those rates increased to rates between $17,126 and $20,700.

In 1990 international students taking the same course load would have paid just under $3,000. This fall international undergraduate students will pay $24,627 per year if they take a full course load in the John Molson School of Business.

“If you’re an international student and you get jailed, honestly the odds are you’ll just get sent back to your country.” — Lucas Mesquita

Lucas Mesquita, who just finished working two years in Concordia’s International Students Office as a social engagement coordinator, told The Link he’s met a lot of international students burdened by financial stress. He explained that stress is further exacerbated by adapting to a new culture and endless job searches.

“Many of the students that need jobs are not actually employed, they’re looking and they can’t find,” he said. He said he worries about the stress that increased tuition rates will put on international students, noting that many of them face social isolation.

“Here people go to class and go back home after. People don’t talk in class very often, they don’t bond in class,” he said. “I believe students are at risk of being alone, or feeling overwhelmed.”

Building Momentum

Hough-Martin said the business model of shifting tuition hikes onto international students is effective since those students tend to protest less.

“International students are more precarious, and as they have immigration status that can be revoked they’re less likely to take bigger steps against the government than domestic students are,” she said. “They’re betting on Canadian and Quebec students not caring about international students’ precarity as much as their own pockets, and so think we’ll be willing to throw some under the bus for our own benefit.”

Mesquita, an international student throughout his undergrad, also echoed the same feeling.

“You don’t want to cause trouble,” he told The Link. “When you’re so busy and overwhelmed with everything, I don’t know if you’re going to feel like going to the streets in protest where you could get arrested. Even when I was still a permanent resident, in the beginning of my degree, I started getting involved a little bit with the CSU’s protests (against international tuition hikes in 2016), but I was wondering ‘I’m a permanent resident, what if I get jailed?’”

“If you’re an international student and you get jailed, honestly the odds are you’ll just get sent back to your country,” he added.

When it comes to organizing a mass movement against international tuition rates, Bouslikhane acknowledges it won’t be an easy task. “[In 2012] it was an application all throughout the province, whereas now it’s going to be more sparse,” he said.

For it to work, he said provincial student associations may need to set their differences aside and be willing to collaborate with each other. “If we all agree that we’re against deregulation surely there’s aspects we can collaborate on—eventually,” he said. “I can see provincial student associations joining forces as they did in 2012.”

_600_375_90_s_c1.jpg)