In 2020, Provincial Law Still Forbids Women From Taking Husband’s Surname

How Quebec’s 1981 Law Reinforces Patriarchal Values

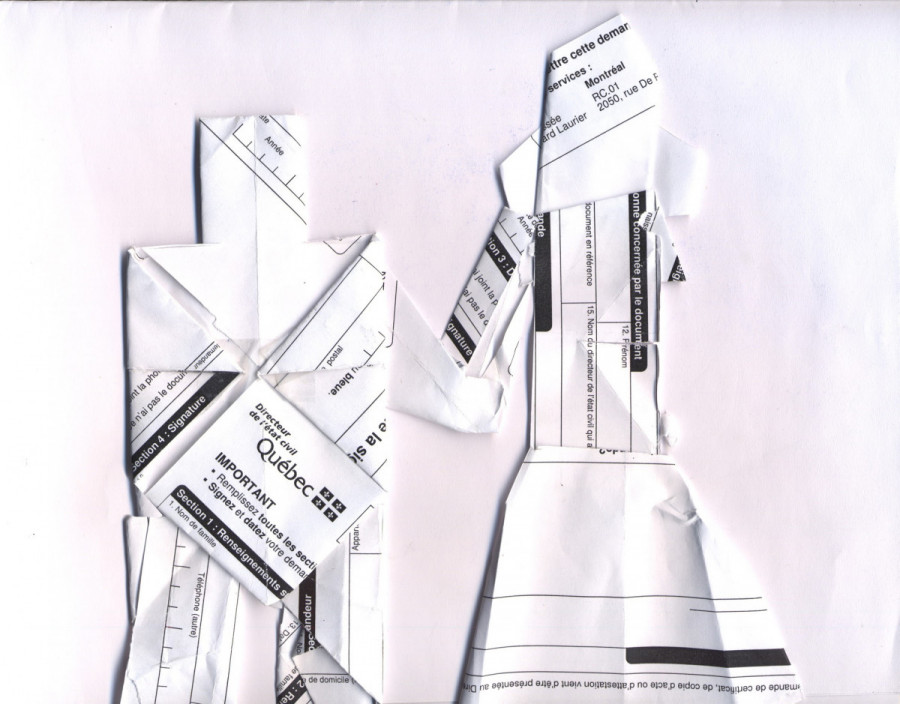

Under Quebec’s Civil Code, both spouses must keep their surname after they marry, thereby protecting the woman’s identity the government is so threatened she will lose after marriage.

Sounds a tad archaic, doesn’t it?

Some might argue the Quebec government is actually a proponent of women’s rights.

The 1976 Quebec Charter of Rights outlined the passage of a 1981 provincial law intended to promote gender equality.

With this law, a woman’s maiden name remains her legal name after marriage and cannot be changed without the authorization of the court—which isn’t an easy task.

A name change may be refused for many reasons and additional documentation can be requested, even after the fee is paid, which can be an undue burden for someone seeking to make a personal choice.

This all sounds like a way in which the Quebec government can control the population in correspondence to its values and beliefs.

Although a married couple may use each other’s surnames by hyphenating them with their birth name, these names are not legally recognized by law.

Through a feminist lens, this means a woman in our society is unable to exercise her civil rights, using her husband’s last name.

This is an infringement on women’s rights and their ability to make decisions for themselves.

What empowers one woman may oppress another.

The Quebec government’s choice to continue enforcing this law shows that it does in fact share the patriarchal view that women are inferior and, ultimately, need these sanctions in place to protect them from society.

This reflects the spirit of Quebec’s Bill 21, which places a ban on religious symbols for public workers in positions of authority to promote the so-called religious neutrality of the state.

This bans women in public positions from wearing the hijab, which in turn oppresses them.

However, the days of a woman living in her husband’s shadow for the whole of their married life is no longer as pressing an issue.

Women in Quebec in the twenty-first century are generally no longer as threatened by men—professionally or financially.

Women are mostly independent now, and they choose to engage in matrimony as a personal choice that complements their lives.

Marriage no longer entails a woman signing herself over to her husband and abandoning her own ambitions and rights.

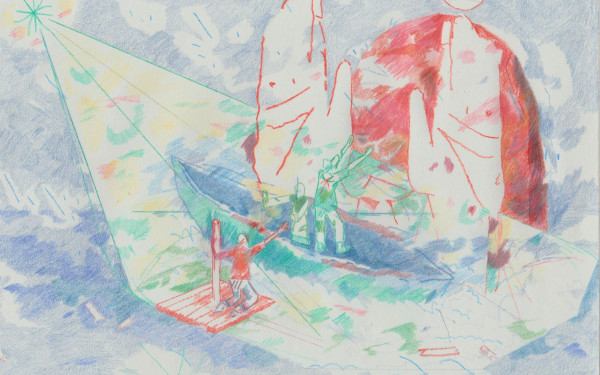

If anything, women assuming their spouse’s surname today might serve to reinforce the strong bond that is shared between them.

It may also serve to legitimize the relationship, in their own eyes and in those of others.

Also, the ability to have a legally recognized shared surname might serve to ensure there would be a sense of connection between both parents and their children.

Having a shared surname between all members would group the whole family as one unit.

If only the government could see it the same way some women do.

Whether Québec is disguising its patriarchal intentions as progressive, or truly believes it is pushing feminist legislation, this law needs to be amended to fit the times we live in.

Women should have the right to choose how they want to live their lives.

Taking this law into consideration is part of that discussion.