Illustrating a Point

Raymond Biesinger on Communism, Consumerism and the Black and White

To Raymond Biesinger, facts are sacred.

“The world has lots of abstract expressionism, things where people are not interested in controls,” the 32-year-old commercial illustrator told The Link. “I’m about back story, research and content.”

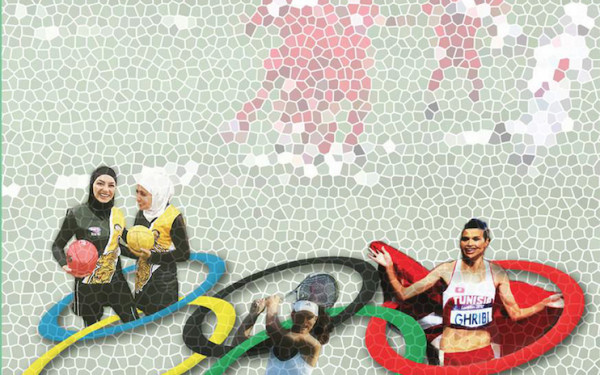

His illustrations are a series of stark contrasts. Part collage and part infographic, he evokes zine culture and tries to find a unity of purpose in collections of scattered facts.

Something that’s always on his mind with each illustration is being able to make an argument and have each element be rational and relatable, said Biesinger.

His new book, Black and White Illustrations, covers illustrations he did between 2002 and 2012 and is being released on Dec. 13 at Drawn and Quarterly.

It covers the first few years of his career, from putting together band posters and house party postcards for friends to the wide variety of commercial and nonprofit commissions he now

entertains.

His illustrations, both in black and white and in colour, have appeared in The New Yorker, Spin, The Economist and Le Monde Diplomatique, among others.

Biesinger’s approach to his work is shaped by his “minimalist maximalist” philosophy. “It’s my intent to shun decoration, to find a purpose,” he explained. He tries to put as much information as possible into the sparsest format.

Biesinger got his start in illustration around 1999, while he was a student in political history at the University of Alberta.

The Gateway, the school’s paper, needed some comics drawn on short notice. Biesinger never drew professionally or considered himself much of an artist, but decided to throw his hat in the ring. He was limited to black and white because of the high cost of colour pages, but learned to appreciate the constraints he was given.

To this day, he aims to keep clarity in mind.

“I impose limitations and work within them, get out the basic shapes,” he said. “One interpretation of maximalism that I like is to take something simple, and work incredibly fast at it, and for a long time.”

Biesinger’s art is done digitally, but his interactions with his computer are a lot more restrictive than most digital artists who are concerned with manipulation.

“I use my computer as scissors and a Xerox machine,” he said. He copies and pastes different elements of an artwork and turns the contrast to 100 per cent, making mostly minor tweaks after that.

“We’re really incredibly wealthy,” he said of the technologies that make work like his possible for a one-man shop. “One person with a laptop can do what an entire small office could.”

The need to always back up an argument and be able to deploy reason has remained crucial to him. “I try to be always purposive,” he explained. “It’s a response to empty politics. We have a government that refutes hard science and avoids hard facts.”

“I impose limitations and work within them, get out the basic shapes. One interpretation of maximalism that I like is to take something simple, and work incredibly fast at it, and for a long time.”

—Raymond Biesinger

The Conservative government’s decision to dismiss climate research and control what federal scientists say to the press is one he finds especially irksome; he thinks that the lack of clarity and large volume of information we’re confronted with is best dealt with by having a clear sense of an end in mind.

Politics and history, he said, are “on my mind an awful lot.” He began reading radical works in university and Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels’ Communist Manifesto made a particular mark on him. “I was very interested in people who wanted to change the world, for the worse or for the better,” Biesinger said.

Over the decade he’s been illustrating, Biesinger’s work has appeared in some of the highest-circulation and most influential publications in the English-speaking world. Recently, New York advertisement agency Saatchi and Saatchi contracted him to make a series of colour illustrations that were used as the basis for a campaign. Despite this, he doesn’t find consumer culture to have a sudden allure to him.

“I’m not excited about consumer society,” he said. “I make my personal life as simple as possible. I don’t own a cell phone.”

When it comes to the high-profile corporate clients, he has no illusions about their place in things. “I try and get as much out of them as I can, and not give anything back. It lets me volunteer my time for causes that matter to me.”

Biesinger’s work as an illustrator has grown in tandem with his place as one-half of the garage rock duo The Famines. The two-piece consists of him on guitar and vocals along with a drummer, Garrett Kruger. They play without any pedals or effects. “It’s a reaction to all the technology razzle-dazzle that’s sold to people,” Biesinger said.

“I’m not enthused by musicians not willing to stand behind their lyrics,” he said. Saying they’re ambiguous and open to interpretation is a “total copout. It’s the equivalent of saying our conversation didn’t mean anything.”

His book launch at Drawn and Quarterly the week after next will give him a chance to practice a newfound skill: talking about his work to others. “I appreciate having an audience,” he laughed.

Launch for Black and White Illustrations by Raymond Biesinger / Dec. 13 / Drawn and Quarterly (211 Bernard St. W.) / 7:00 p.m. / Free