How Did Your Candidate Get Here?

Turns Out, Anyone Can Have Their Picture on a Plastic Sign

It’s federal election season in Canada!

The time of year for about 8000 weird photo ops, awkward questions from family members about who you’re voting for in October, and the almost literal overnight appearances of all those colourful plastic signs with the faces of the people running in the various ridings all over the country.

If you aren’t familiar with Canadian politics, or need a refresher after following the Democratic party’s nomination process in the States, here’s a quick rundown: instead of voting for the Prime Minister directly, you vote for the candidate seeking election in your electoral district, more commonly known as a riding.

Ridings aren’t always stable in their dimensions or the area they cover.

They are usually revised based on the population of the area, as overseen by an independent commision for each province (as to avoid the problem of gerrymandering—the partisan redrawing of electoral districts—which is an omnipresent issue in the United States.)

The party who elects the most representatives wins the election, with the leader of the party usually named the Prime Minister.

Interestingly enough, you don’t need a majority government to win, just the most candidates, which leads to the almost always frustrating minority government.

Once the signs are up, a lot of people will probably have the same nagging thought at the back of their head: “I have no idea who any of these people are.’’

How Did You Even Get Here?

It’s easy to think being a candidate requires notoriety, or a particular skill set, or even a basic background in politics of any kind.

While that’s not always untrue (more on that later), in reality, almost anyone can run to be a federal member of parliament.

It’s easy to think that being a candidate requires notoriety, or a particular skill set, or even a basic background in politics of any kind. While that’s not always untrue (more on that later), in reality, almost anyone can run to be a federal member of parliament.

According to Elections Canada, to be eligible as a candidate in a federal election, you only need to be a Canadian citizen who is older than 18, and submit a nomination form—in which you need 100 people from the riding to consent for your running—either physically or online a mere 21 days before the election.

You also have to be admissible under part 65 of the Canadian Elections Act.

Inadmissible people include the incarcerated, provincial members of parliament, and election officers, to name a few.

It’s a very simple process that allows a lot of people to run for office, which can lead to some goofy candidates.

This includes my current personal favourite, the satirical Rhinoceros Party’s Maxime Bernier, currently running in the riding of Beauce against the leader of the People’s Party of Canada, Maxime Bernier. His slogan? “If you’re not sure, then vote for both!”

Even I, a 23-year-old university student, could run for office as an independent candidate in my home riding of Brossard-Saint-Lambert, as long as I filled out the form in time.

Now, here’s the caveat on why that isn’t exactly a great idea.

First of all, I’d consider it a massive success if I got more than exactly two votes, and not just because not even my parents would vote for me.

It’s incredibly hard for anyone not running for one of the main parties to get elected.

Before the election, only eight of the 334 MPs sat as independants, and none of them were elected as such.

Of course, I could try to run as a candidate for one of Canada’s many different parties.

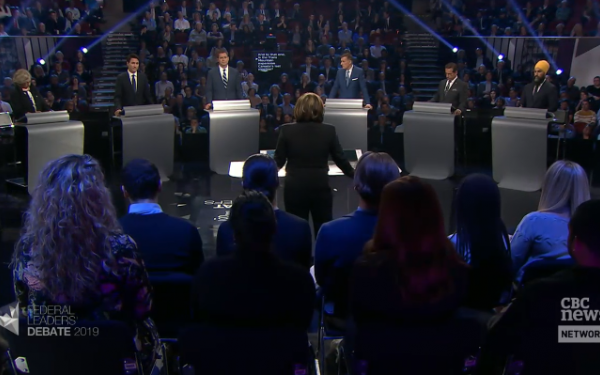

Did you think having the Liberals, Conservatives, New Democratic Party, the Green Party, the Bloc Québécois, and the People’s Party of Canada was already a lot?

There are actually 16 different registered parties as of May 2019!

These parties include, to name a few, the aforementioned Rhinoceros Party, the Communist Party of Canada, the Alliance of the North—who are as much to the political right as their name implies—and the Marijuana Party.

But, these parties usually don’t have candidates in every riding come election time.

When they do run, they usually get a very small amount of votes.

Same thing for independent candidates; not being under the umbrella of one of the major parties can make it very difficult to get elected.

Even candidates from the Bloc Québécois and the Green Party, two parties with name recognition, struggle to get elected.

There are a lot of possible reasons why being under a major political party’s umbrella is usually advantageous for a candidate.

For example, these parties have more money to run effective campaigns for their candidates.

There is also the fact that some people vote for the party they want to win, as opposed to which candidate is running.

Voters can get into an electoral rut of sorts, with attitudes like deciding that they’ve always voted for the same party in the past, so why change now?

That means these people might vote for anyone the party presents in their riding.

This doesn’t mean that parties don’t try when selecting their candidates, but instead they can sometimes choose safer or more conventional candidates for stronger ridings.

For ridings that are up for grabs, or ones where a party has been traditionally weaker, though, they’ll bring out the big guns

A Star (Candidate) Is Born

Name recognition is one of the most important factors in a candidate’s campaign success.

For your average candidate, it can come either from being up for re-election, or by candidates putting themselves out there and making public appearances so as to gain name recognition.

“Fortune favours those who stay busy and in the public eye for the four years between elections,” says Paul Mason, a Dundas-based organizer of NDP campaigns.

In that sense, someone who the public at large already knows should have a big advantage in that department, right?

That’s exactly what the star candidate is supposed to be: someone who is already, politically or otherwise, known to the general public, or at least a large enough portion of the general public to make them theoretically electable.

The celebrity of a star candidate can vary.

More often than not, they’re someone who established themselves politically at another level of government.

Former mayors, provincial elects, and even retired politicians asked to run one last time make up the vast majority of star candidates.

They are also often unknown to the vast majority of people outside their riding.

Someone who lives in Rosemont will almost certainly not know who a star candidate running in Burnaby is, for example.

Other times, however, parties think outside the political box when choosing a star candidate, sometimes picking candidates with little or no prior political experience.

Marc Garneau, the MP for Notre-Dame-de-Grâce-Westmount since 2008 and Minister of Transport since 2015, had no prior experience in politics before he joined the Liberal Party in 2006.

What he did have, however, was name recognition.

Before his now decade long political career started, Garneau was an astronaut, and a famous one at that.

He was the first Canadian to ever go to space, in 1984 aboard the Challenger space shuttle, and was also the president of the Canadian Space Agency from 2001 to 2006.

He would go on to win his riding in 2008, and has since been reelected twice.

A few of the star candidates running in the 2019 election include Angelo Esposito—no relation to hockey legends Phil and Tony—running for the Conservatives in Laval’s Alfred-Pellan riding.

He’s best known for being taken twentieth overall in the 2007 NHL draft by the Pittsburgh Penguins, then proceeding to play zero regular season NHL games.

Steven Guilbeault, an environmental activist and one of the founders of Equiterre—a non-profit community agricultural organization—will run for the Liberals in Laurier Sainte-Marie.

Réjean Hébert, who was the provincial Minister of Health and Social Services in Pauline Marois’ Parti Québécois government from 2012 to 2014, will run for the Liberal party in Longueuil-Saint-Hubert.

With the varying competency of star candidates, being able to run in basically any riding you want as long as you fill the conditions, and the vast difference between the impact an MP has on their community versus the impact the winning party has on the country as a whole, is the current system working as intended?

Is it giving us the option to vote for the best possible candidates, just the most convenient, or most popular at the lowest denominator level?

These are questions Western-style democracies, not just Canada, need to answer.

So no matter who you end up voting for in October, remember this: just because someone is running in your riding, doesn’t mean that they have any political experience, or celebrity, or even a real platform.

It’s easy to look at the party figureheads and think of voting in the big picture, but remember to think about the little picture too, in this case the pictures of the candidates that have now popped up in your neighbourhood.

_600_375_s_c1.png)

_600_375_90_s_c1.jpg)