How Concordia is Preparing For the Anti-Sexual Violence Legislation

How the University is Handling Sexual Violence on Campus, With Deadlines to Meet Demands Approaching Soon

Concordia has submitted a renewed policy on sexual violence, but how close to meeting their other obligations are they?

The first deadline for Quebec universities to meet their obligations under Bill 151, aimed to prevent and fight sexual violence on campuses, has passed on Jan. 1, 2019, with Concordia submitting a renewed policy on sexual violence.

After Quebec passed Bill 151, universities, and CEGEPs in the province were given until Sept. 1 2019 to put in place new rules aimed to protect their students from sexual violence.

Concordia will need to uphold other commitments towards the provincial government, and has founded a permanent committee on sexual misconduct and sexual violence. The committee exists to revise and enforce Concordia’s policy on sexual violence, which was first implemented as a “standalone” policy in 2016 and updated to be submitted for Jan. 1. The university will also implement mandatory consent training for students, soon to be required across Quebec, and staff and faculty will also be able to access the same training. Additional funding for the Sexual Assault Resource Centre is also planned.

The Policy

Lisa Ostiguy, special advisor to the provost on campus life, said this sexual violence policy reflects an updated version of one made in 2016, Concordia’s first standalone policy on sexual violence. “The main changes that we made are much more accessible in terms of language,” said Ostiguy.

One of the critiques from the Task Force on Sexual Misconduct and Sexual Violence—a group mandated by the university to consult issues and policies related to sexual violence and misconduct—released in a report mentioned that students lacked awareness about the policy and resources for sexual violence on campus.

In an interview during the summer semester, when Concordia Student Union’s General Coordinator Sophie Hough-Martin was not yet on the standing committee, she argued the report pinned too

much of the blame on students not understanding how to use the university’s existing resources.

Ostiguy said that she found it wasn’t only students who weren’t aware of existing policies and resources, but also that faculty and staff were out of the loop. She said the standing committee is

addressing how to better communicate what the university has in place, as the school’s website will be updated soon to address this.

The committee will also be looking at how to engage more people in understanding Concordia’s sexual violence policy, with Ostiguy mentioning a breakdown of the policy will be included in mandatory consent training for students.

The updated policy was approved by the Board of Governors on Dec. 12 2018. Ostiguy said maintenance of the policy will be ongoing.

“Now that we have a permanent standing committee, we’re going to always be hearing things that may or may not be successful,” she continued. She said the committee will be open to critique and questions on the policy. Ostiguy said a formal review of the updated policy will be done in one year.

Related Articles:

- Concordia Hosts Sexual Misconduct and Violence Consultations, In Preparation for Bill 151

- Concordia Considering Online Consent Training For Students

- Concordia and McGill Students Stage Walkout to Denounce Campus Sexual Violence

- Infractions of Sexual Harassment See 78 Per Cent Increase at Concordia

- A Timeline: Sexual Violence at Concordia and its (Mis)Management

Consultations

Over the fall semester, the sexual violence committee hosted four public consultations, accessible to all students, faculty and staff. These one hour long “community conversations” sought input on what students think of sexual violence and sexual misconduct on campus, and how the university should best address the issue.

“When we did the task force process from January to June last year we had a lot of consultation opportunities,” said Ostiguy. “And what came out of those conversations and consultations was that we need an ongoing conversation around sexual violence and sexual misconduct.”

She said sometimes there’s a lack of awareness of opportunities to informally discuss concerns, so the consultations give a chance for the community to provide input to the sexual violence committee and become familiar with its members.

She said the new year will hold more consultations, as two are scheduled in January, with more in February, March and the following months.

Ostiguy said minutes are not being taken during these consultations because the university wants to maintain a casual conversation and not expose personal experiences students or faculty may be discussing with the committee during these meetings. She said people who want to give input outside of consultations are also available to email her.

Lack of Transparency

Senior Legal Counsel Melodie Sullivan told The Link that minutes are not kept for the private meetings of Concordia’s sexual violence committee, making it difficult to track how often student representatives from the CSU and Graduate Student Association are attending these meetings. Though minutes for sexual violence committees for Quebec schools are not required by the provincial government, annual reports of these committees will be required so the province can oversee how well school’s are meeting Bill 151’s demands.

“As university students and young adults, I believe we are often put into situations where consent might be a grey area. These trainings help us navigate these grey areas.”

— Curtis Gass

Online Consent Training

Jennifer Drummond, coordinator of the SARC, said online consent training for students will be rolled out for the fall of 2019.

Concordia has offered consent training for several years through the SARC, however until obligations under Bill 151, this training has been voluntary. The training is only given when a group requests it, such as student associations—with exceptions toward varsity athletes, said Drummond. For privacy reasons, the university wouldn’t reveal which groups have made requests for consent training or doesn’t allow outsiders to observe trainings for signed up groups.

Finance student and Stingers hockey player Curtis Gass underwent the consent training after joining the Stingers and shared his experiences.

“The training we receive is a workshop presentation that [lasted] around an hour,” he said. “Usually two to three speakers will come and talk to us about consent.” He said there was a presentation during which they invited the team to ask questions and give their opinion on certain subjects.

“There are group discussions and scenario training as well, where we divide into groups and talk about what should be done in specific situations,” Gass said.

Drummond says the SARC doesn’t have a standard playbook for its training, but rather tailors sessions for each group it engages with. “It depends on the facilitator and it depends on the group […] we like to cover what is sexual violence, what kind of behaviours fall under that, how prevalent is this issue […] and then we talk about consent.”

Gass hadn’t realized varsity athletes were the only group obligated to take consent training. However, he thinks the university is making a good decision rolling out the training to all students.

“As university students and young adults, I believe we are often put into situations where consent might be a grey area,” said Gass. “These trainings help us navigate these grey areas.”

Whether mandatory training will go smoothly is yet to be seen. The SARC will be responsible for setting up the workshops and training a staff of volunteers who will run the training. Drummond said the SARC is continuing with its in-person training, however it appears at the moment the majority of training for students, staff, and faculty will happen online.

Ostiguy said for the past year Drummond has been working on various training modules to be administered both in person and online.

“This was before any announcement was made with the government,” Ostiguy said. “The idea with the online training is that we’ve got a big community and we want to make sure that the information is accessible to as many people as possible.”

In terms of how it’s going to be presented, Ostiguy said there’s a training committee with 14 members that will assess the logistics of the training.

SARC Overshadowed By the CSU

Prior to the last consultation at the downtown campus, the CSU put up posters to rally students to “flood Concordia’s community conversations,” pointing out that the consultations were held at 9 a.m. and 10 a.m. during finals. “That’s certainly not enough to keep us away! […] make our voices heard and demand more from our institution” the CSU posters read.

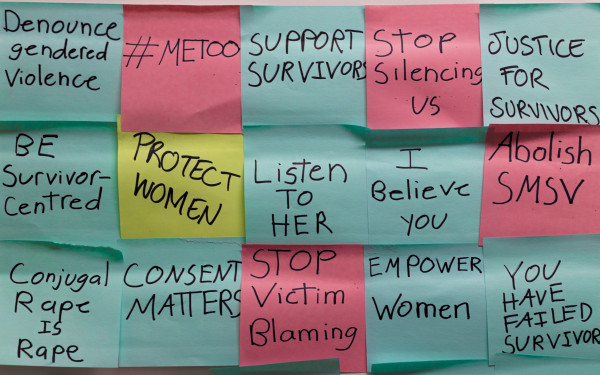

If you’ve walked around campus recently you may have noticed the plethora of sexual consent awareness posters stating things like, “Never asking for it.” These are not connected to the school’s efforts or SARC. The student union is committing to bringing awareness of consent to campus life. Less visible are the small handful of posters warning things like, “Most sexual assaults happen in the first eight weeks of class,” which are placed in the Loyola—Downtown shuttle buses and around campus by the SARC.

Established in 2013, the centre has grown from being a one-woman operation. The SARC now has multiple full-time staffers to help students who are victims of sexual violence. Yet Drummond said SARC’s presence on campus is currently overshadowed by the CSU’s campaign.

“We’re limited in how much we can have a visual presence on campus, for example the CSU campaign is much more visible because they have a much bigger budget than us,” said Drummond.

The CSU has an annual budget of $4.5 million—$50,000 of which is dedicated to union’s advocacy campaigns, while the SARC’s entire operating budget was $24,000 between May 2017 and April 2018, according to an expense report obtained through an access to information request.

The university has increased the SARC’s funding and the organization by recently adding two new employees. Come next semester, SARC is getting a new full-time receptionist and an additional full-time staff member. This is a far cry from when the SARC opened its doors and Drummond was the sole staffer.

The centrepiece of Concordia’s new policy is consent training. But given the SARC was only run by Drummond until 2016, the logistics of providing consent training to more than 46,000 students is daunting. Hough-Martin said the CSU is looking to set up meetings with the SARC to look at the shared priorities they have considering sexual violence to ensure more attention to the issue.

“The SARC is going to play a big role in training and education, the standing committee fully recommends that [Drummond] gets more resources and so does the Office of Rights and Responsibilities,” said Ostiguy.

“The government gives a bit of funding to go along with Bill 151 to implement changes,” she said. However, the university is still looking into how often Concordia will be obtaining funding.

With files from Savanna Craig and Miriam Lafontaine

_600_375_90_s_c1.jpg)