A Timeline: Sexual Violence at Concordia and its (Mis)Management

Revisiting Concordia’s Sexual Violence Problem

Just one week into the new year, Concordia University was thrown into its worst public relations nightmare in recent years—one that managed to maintain the attention of mainstream news media for subsequent weeks.

The whispers of sexual misconduct that had been echoing through the university’s halls for years—some say as far back as decades—finally became so loud that university’s administrators could no longer ignore them. A statement was released; a press conference was held; an investigation was launched, and a task force was formed. But many say this action is too little too late and that Concordia’s response to this alleged culture of sexual violence has been lackluster at best.

Here’s a look as to why that is through an overview of the history of sexual violence at Concordia.

1990s

Famed Montreal author and Concordia graduate Heather O’Neill tells the CBC this year that she was sexually harassed by a professor while she was a student in the school’s creative writing program in the 1990s. The alleged misconduct within the program was described by other former students as being an open secret.

2009

A student is sexually harassed by a professor from Concordia’s philosophy department. After attempting to report the incident, the student is allegedly told that she is not allowed do so and that she should not disclose what happened to anyone else. She is then bounced around for eight years while attempting to have her case heard.

2011

The Centre for Gender Advocacy, with support from the Women’s Studies Student Association, calls on Concordia to establish a sexual assault centre due to a high rate of sexual violence complaints. It takes two years for a centre to be established at the university.

April 2013

Concordia announces its plans to open a Sexual Assault Resource Centre.

October 2013

A student is allegedly groped in Concordia’s downtown Webster Library. At the time of the incident, a Concordia spokesperson says that there had been three reported incidents of sexual harassment that year. That number increases to 19 by the end of that academic year.

_900_600_90.jpg)

November 2013

The SARC opens its doors with Coordinator Jennifer Drummond as its only full-time employee. The centre operates largely through the help of volunteers. SARC receives its second paid employee three years later in 2016.

August 2014

Former Concordia director of residence life D’Arcy Ryan (now Director of Recreation and Athletics) asks that a petition mandating consent workshops in the university residences be taken down, allegedly saying that the university acts as a landlord, not an authority and saying that “he felt it wasn’t the best way to begin a dialogue around those kinds of issues.”

October 2014

Former Concordia student Emma Healey publishes an essay titled “Stories Like Passwords” that retells a sexual assault she experienced at the hands of an unnamed professor from Concordia’s English department. The article is circulated widely within the department.

February 2015

In response to Healey’s essay, students from the English department write a letter to the then-chair requesting a formal statement from the university to address the “toxic atmosphere” in the program. The student signatories of the letter are then invited to a meeting with a representative from Human Resources to discuss the issue.

March 2015

Cathy, a student who was assaulted by her ex-boyfriend on campus, files a complaint with the university’s Office of Rights and Responsibilities. Following significant delays and what she says is an unfair verdict on behalf of the university’s tribunal, the school gives her harasser 30 hours of community service, despite the fact that he plead guilty in court. In response, Cathy decides to take her case to the Quebec Human Rights Commission.

In the same month, Concordia prepares to review its sexual assault policies. Up until this point, Concordia did not have a clear definition of sexual violence in its policies on harassment, sexual harassment, and psychological harassment.

April 2015

Mei-Ling, a former student politician who spoke anonymously, files a complaint with the Quebec Human Rights Commission following race-based discrimination and sexual harassment within the Arts and Science Federation of Associations just over a year earlier. This high-profile case, which receives mainstream media attention, kick-starts ASFA’s attempts at rebranding in an effort to move away from what Mei-Ling described as a toxic culture of misogyny.

1_900_600_90.jpg)

August 2015

Concordia releases its report on its review of the university’s existing sexual assault policies. Recommendations include mandatory sexual violence training sessions for senior administrators, student executives and athletes, athletic coaches, residence assistants, students living in residence, and key faculty positions. It also recommends the adoption of a policy specifically meant to address sexual violence with specific procedures as well as allocating more resources to SARC.

September 2015

SARC begins providing workshops to Concordia’s residence assistants, and offering consent workshops to Concordia’s varsity teams, in response to controversies surrounding sexual violence and athletes at universities in Ontario and Quebec.

September 2016

Concordia releases its new stand-alone sexual violence policy. Included in it is the establishment of a sexual violence response team, a group whose role is to help those who file a report through the process. Concordia’s Code of Rights and Responsibilities, however, still supersedes this policy which leads to some confusion due to differences in language used and about which procedure to follow.

October 2016

Quebec Higher Education Minister Hélène David announces a series of province-wide consultations on sexual violence on post-secondary campuses following reports of a series of sexual assaults at Université Laval that month.

December 2016

Concordia hires Ashley Allen, a service assistant for SARC. She becomes the centre’s second paid employee.

2016-2017 Academic Year

Between 2016 and 2017, the university’s Office of Rights and Responsibilities receives 23 reports of sexual harassment.

February 2017

SARC moves from its GM building location to a larger space on the sixth floor of the Hall building in efforts to make it more accessible.

April 2017

Concordia amends its Code of Rights and Responsibilities for the first time since 2010 to unify it with its sexual violence policy and add more protections for community members who go through the tribunal process.

August 2017

The provincial government announces $23 million in funding for post-secondary institutions to tackle sexual violence on campus. This comes ahead of the approval of Bill 151, a law that mandates how post-secondary institutions must deal with the issue.

October 2017

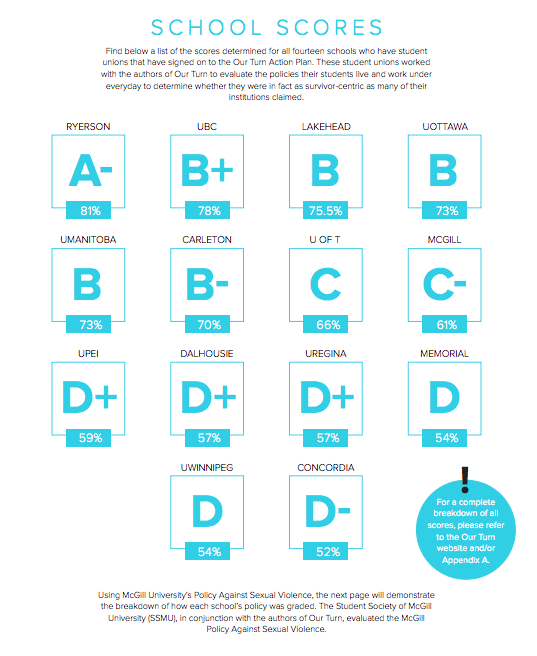

Concordia is given a D- rating by Our Turn, a national action plan that examined the sexual violence policies of 14 universities across Canada. Concordia received the lowest grade as a result of its policy not being adequately survivor-centric, meaning it does not “prioritize the rights, needs, and wishes of the survivor,” according to Our Turn’s report.

December 2017

Quebec adopts Bill 151, also called an Act to Prevent and Combat Sexual Violence in Higher Education Institutions. This mandates that post-secondary institutions have a sexual assault resource centre and a sexual violence policy, and that there be mandatory training for students and staff.

January 2018

Concordia graduate Mike Spry recounts witnessing an alleged toxic culture of sexual misconduct within the university’s creative writing program in a widely circulated blog post, acting as a catalyst for the university’s sexual misconduct scandal that continues to unfold.

Days after Spry’s post, Concordia President Alan Shepard announces that two investigations will be launched: one third party investigation into specific claims involving professors who were later revealed by the CBC to be David McGimpsey and Jon Paul Fiorentino, and one internal investigation into the alleged toxic culture of the English department. Shepard also announces the establishment of a 12-member task force to review Concordia’s sexual violence policies. A report of their findings is set to be released later in 2018.

In the weeks following, Shepard also says that the university plans on allocating more resources to SARC to better serve students, including hiring an additional employee.

_900_643_90.jpg)

_600_375_90_s_c1.jpg)