Gendered Stigma and Alcoholism

Social Pressures Prevent Women From Getting the Help They Need

Until recently, we didn’t know much about women’s relationship with alcohol, even though alcohol abuse among women has been rising steadily for years.

Most of the studies on alcoholism that were conducted in the last century were only carried out with male subjects. This is a problem.

Lately, studies have shown that women and men drink in different ways and for different reasons. This means that a lot of what we know in regards to alcohol consumption and abuse has to be thrown out the window when we’re talking about women.

For one thing, we’ve discovered that since women have on average less water in their bodies, they’ll often have a higher blood alcohol level than men do even if they were to drink the same amount. That—paired with the fact that women tend to be smaller in stature than men—means that it can take a woman as low as half the amount of alcohol to get drunk as it would a man. Women also have the potential to develop health complications from abusive drinking at an earlier age and at lower consumption levels than men.

However, the differences are more than just physical—the psychology behind alcohol consumption and abuse differs, too. While studies have concluded that there are a variety of reasons men will drink—be it dealing with anger or to have an easier time socializing—a 2008 study conducted by Dr. Stephanie Covington concluded that women tend to self-medicate using alcohol to deal with trauma. Covington’s study goes along with many other studies regarding this issue.

One in three women worldwide have been physically or sexually assaulted in their lifetime. Women who were sexually assaulted are six times more likely to abuse alcohol than women who weren’t. Many female problem-drinkers report abusive or neglectful early years. So when we’re talking about women and alcohol, trauma needs be a part of the conversation.

There’s another major difference between male and female problem-drinkers that we don’t tend to talk about—the stigma.

In 1988—around the time when we began to pay more attention to women’s relationship to alcohol—a study conducted by the University of Michigan revealed that women, both with and without alcoholic tendencies, had more negative feelings toward female problem-drinkers than male problem-drinkers. The women in the study also agreed that society as a whole seems to hold this view.

Though the study came out almost 30 years ago, experts say this stigma is alive and well today. In a 2009 issue of the the Canadian Women’s Health Network’s periodical, Carolyn Shimmin wrote that it’s “important to understand that stigma experienced by those living with addictions varies by gender and therefore requires different approaches and treatment options.”

Clearly, there is no ‘one size fits all’ treatment that works regardless of gender.

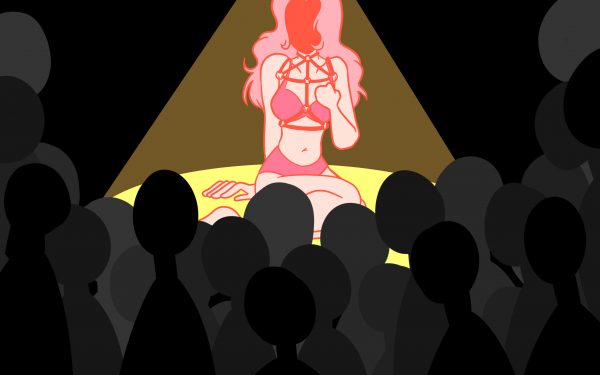

According to some experts, this stigma comes from the role we commonly attribute to women in our society: that of a mother or caregiver, who should uphold the morals of society. It’s also been attributed to the fact that women who excessively drink are often stereotyped as being sexually promiscuous, an association we do not make for men in the same situation.

Women problem-drinkers being stigmatized, shamed and rejected for their habits makes it that much more difficult for them to seek the help they need. The World Health Organization has found that men are far more likely to disclose problem-drinking to a medical professional than women.

Furthermore, because alcohol abuse in women is often triggered by violence, the healing process addresses that violence, and they are made to relive it. Reaching out for help can therefore be a difficult and emotionally exhausting experience.

We can’t ignore how these factors play into treatment for alcohol abuse. Clearly, there is no “one size fits all” treatment that works regardless of gender.

In much of North America, experts have come to realize that their treatment methods need to be tailored to women’s needs if they are to be effective. Here in Montreal for example, the McGill University Health Centre has women-only addiction support group meetings twice a week. They explain on their website that, because violence against women is most often perpetrated by men and is closely tied to addictions for women, “it is important to provide a safe and supportive environment where male/female dynamics does not play a role.”

What needs to change now are our societal notions that stigmatize and isolate women dealing with alcohol abuse. Progress in the treatment methods are well and good, but that doesn’t change the fact that women have a much harder time than men do when it comes to admitting that they have a problem in the first place.

That isn’t to say society is totally accepting of male problem-drinkers. People with addictions often deal with rejection and isolation, regardless of their gender. But until women are guaranteed equal footing in this world, it’ll continue to be more difficult for them to reach out when they are in need of help.

Unless it becomes easier and more socially accepted for women to seek the help they need, alcohol abuse among women will continue to rise as steadily as it has been for years.

_600_375_s_c1.png)