Editorial: Montreal, Your Sewage Plans Are Full of It

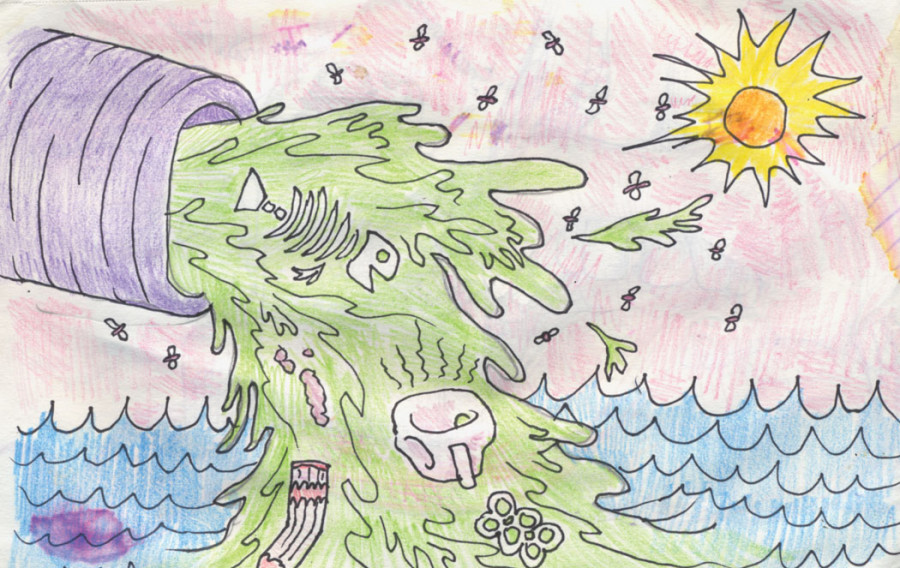

Montreal has taken heat for its plan to flush the city’s crap directly into the St. Lawrence River—but it might be the push we need to fix our underwhelming sewage treatment system.

The story isn’t new, but the eight-billion-litre untreated sewage dump scheduled for next week is being discussed widely in Montreal and across the country. A U.S. Senator, Charles Schumer, has even spoken against the project, asking the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency to intervene, even though the EPA has no jurisdiction in Canada.

The city needs to drain sewers to carry out much-needed repairs while preparing for reconstruction of the Bonaventure Expressway and the snow dumpsite currently beneath it. Before this, Montreal’s sewage management was already struggling to accommodate waste.

The St. Lawrence was treated like a municipal toilet for decades before the 1990s. Dozens of beaches were open until about the 1970s, when the amount of waste dropped into the waterway grew beyond the river’s self-cleaning capabilities. Sewage, snow and rainwater were dumped directly into the river and surrounding lakes without any treatment, before restorative measures, such as a $2 billion sewage processing plant that was installed in the city’s east end, were taken.

In the 2003 spring season, Montreal dumped 10 billion litres of untreated sewage in spring season and another 7.6 billion litres in the fall, according to CBC. Scientists say the eight-billion-litre dump won’t change the river’s ecology, since the current moves fast enough to dilute the sewage.

In an average year, Montreal, like many other North American cities, has a persistent problem with sewage, specifically when it comes to storm water management. Heavy downpours overburden the city’s water system, when rainwater (which is untreated) connects with sewage (which is treated), overflows and bypasses treatment altogether. Homes risk flooding and beaches are closed, because fecal bacteria levels exceed safety standards.

Next week’s expected eight billion litres of waste makes up only one-third of the city’s weekly sewage—which says a lot about how much is being flushed into the system by homes and businesses.

Montreal needs to reconsider water consumption and the way we use our sewers, starting with small measures. The city of Laval and Montreal made it illegal for homes to have their gutters drain directly into street sewers. Residents must now collect rainwater from gutters in a barrel or have it drain into yards. In Toronto, it’s technically illegal to wash your car where the water and suds will enter street drains (though the bylaw isn’t really enforced). Reflecting on the way we use the sewage system is one step, but upgrading our substandard treatment plants is also a must.

In 1999 and 2004, Sierra Club, an environmentalist group, produced sewage management report cards and gave Montreal an F for its system both times. According to Sierra Club, the upside of Montreal’s network is nearly everyone is connected to the sewers that pump all our liquid garbage to the treatment plant in Rivière-des-Prairies. The bad part: it only goes through primary treatment, removing solid waste, garbage and phosphorus and dumps pretty much everything else in the river. This means pharmaceuticals and other toxic substances for marine life are already being dumped in the river.

The city has plans to install an ozonation system by 2018, with provincial and federal help—but some reports question the effectiveness of the process.

Cities like Calgary, meanwhile, received top grades for a sewage system that handles storm water without overflowing, pumps all wastewater through treatment that turns it into compost used on farms and disinfects the water with UV treatment. In D.C., the city’s water utility is implementing Norwegian technology to transform sewage sludge into clean energy, which in turn can help power the waste management plant’s treatment system.

On the 2004 Sierra Club report card, the only city to score worse than Montreal is Victoria—which doesn’t even have a sewage treatment plant. Montreal’s treatment plant is called the third largest in the world—and is one of the youngest. But size isn’t everything when it constantly requires repairs and isn’t even all that great as a system.

Weeks before the federal election, the Canadian government has suddenly taken an interest; Mayor Coderre handed over documents about the dump to Environment Canada on Friday and is expecting a response by Tuesday.

It will take a lot more investment in Montreal’s treatment plant before it catches up to the 21st century. We need a culture shift in how much shit we flush into the river—and that’s worth making a stink about.

ed1WEB_600_375_90_s_c1.jpg)

1web_600_375_90_s_c1.jpg)