Do the police exist to protect us?

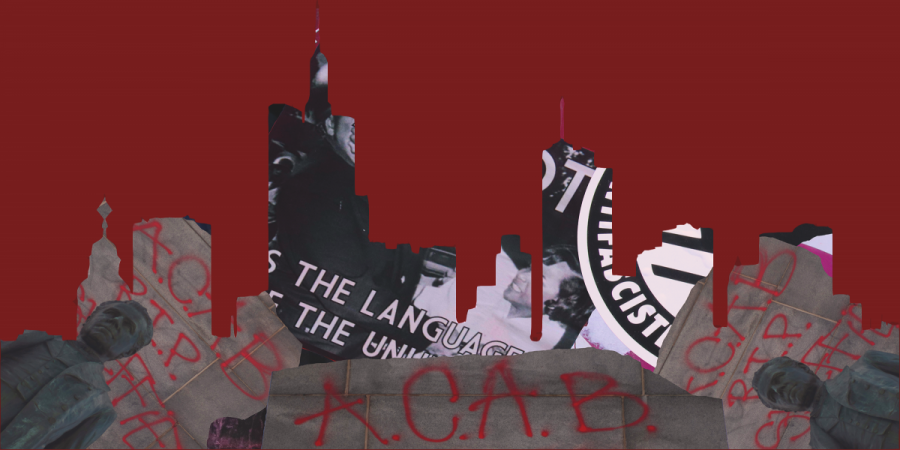

As the sayings ‘ACAB’ and ‘defund the police’ become more popular, attention is brought to police brutality

Whether the police exist to protect or oppress us often depends on whom you ask.

If you ask a Liberal, they might reply that the police exist to protect us all, including minority communities. If you ask a Conservative, they might affirm that the police exist to protect everyone; that the police are colour blind. However, in recent years, light has been shed on the systematic racism this institution is built on and society is gradually becoming more aware of the cruelties marginalized communities often endure as a result of policing.

In the wake of this realization has emerged a slogan: “ACAB,” sometimes written “1312,” substituting the letters with numbers. This mantra of sorts has grown in popularity across social media platforms with the rise of media’s attention on police brutality in the United States and in Canada.

“ACAB” originated in London in the 20th century and originally stood for “All Coppers Are Bastards,” though, outside of the UK, “Coppers” is often replaced with “Cops”. The saying soon found its way in punk culture, allowing it to travel across the Atlantic and into our own society, as we can find it graffitied in almost every neighbourhood in Montreal.

Even at the anti-police brutality protest from March 15, people held signs that read “ACAB 1312”.

It is important to understand why so many people believe that all cops are bastards despite all the “good” police officers seem (read: pretend) to be doing by protecting our communities from crime.

The first modern police force is often thought to be the London Metropolitan Police, established in 1829 by Robert Peel. This agency claimed to prevent crime, but its real purpose was to protect the upper classes and prevent riots and rebellions from the lower classes. Essentially, to maintain the status quo.

Today, the main function of the police is still to maintain the status quo. They do so by attending every protest and making mass arrests. For example, in 2013, in Montreal, they arrested a total of over 530 people over the span of three weeks and two protests—both against police brutality.

During the North American protests against police brutality in the wake of George Floyd’s murder, police wore riot gear and attacked protestors. According to The Independent, one was accused of “stomping” on a pregnant woman, causing a miscarriage. Another was accused of shooting a rubber bullet in the eye of another woman, causing her to lose the eye.

Where does the saying “ACAB” come in? Police brutality has clearly existed since the creation of the first police force, and it is only escalating as people are starting to realize the fundamental flaws in the system. As Victoria Gagliardo-Silver from The Independent puts it, “‘ACAB’ means every single police officer is complicit in a system that actively devalues the lives of people of colour.”

In British Indian colonies, the police had the role of ensuring the natives did not revolt, despite the police force being an overwhelmingly Indian majority. The reason the Indians within the police force did not revolt was that the British had successfully divided the different Indian “races,” and recruited the Muslims from Northern India to join the British in oppressing the “races” that were deemed inferior.

This is exactly why implementing diversity programs in police forces does not work. Hiring more Black cops will not prevent unarmed Black civilians from being shot and killed by police because the police are inherently a racist institution. There’s a reason it’s called “institutional racism.”

“We aren’t talking about some bad apples, we’re really talking about a system built on the oppression of certain communities.” — Marlihan Lopez

In Canada, John A. MacDonald formed The North-West Mounted Police in 1873.

The NWMP, now known as the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, had the colonial purpose of uniting the Northwest to the rest of Canada. One of their main mandates was, once again, not to prevent crime, but to assimilate the Indigenous populations that rightfully inhabited this region in order for the Hudson’s Bay Company could illegally claim the territory.

The Mounties, as they are often called, kidnapped Indigenous children and tortured, assaulted, raped, and murdered them by bringing them to the horrendous residential schools.

The last residential school may have closed its doors in 1996, but the oppression Indigenous communities face due to over-policing is ongoing.

“We aren’t talking about some bad apples [within the police force],” explained Marlihan Lopez from Montreal’s Defund the Police Coalition. “We’re really talking about a system built on the oppression of certain communities.”

DPC is an alliance of several community organizations that have come together in the wake of George Floyd’s murder in order to pressure governments to defund the police and then reinvest in communities.

“Black and Indigenous communities have historically been vulnerable to state violence,” Lopez pointed out, explaining that all one needs to do to understand the systematicness of police violence is to watch the news or look into the history of police in Canada. “It’s time to address these issues [and] to reimagine public safety for all of us,” she concluded.

Of course, changes are not going to happen overnight. According to Lopez, defunding the police and adopting anti-carceral approaches is a process whose end goal is to “invest resources in addressing roots of violence.”

She stressed the importance of reinvesting the resources taken from police departments into community programs, housing services, health care services, gender-based violence programs, and many more public services.

People may view prison abolishment as an unrealistic goal, but Lopez says to “reflect on how government and institutions have a role [in our understanding of prisons].”

She concluded that governmental institutions “haven’t allowed us to imagine any other alternatives [to prisons and police].”

In his book The End of Policing, Alex S. Vitale argues that reforming the police by improving training, implementing diversity programs, or even installing body cameras on officers is unlikely to decrease police brutality. Vitale claims the issue with policing is not abuse of power—but policing itself.

He explains how fighting crime, despite it being what the public believes to be the main focus of the police, constitutes only a small part of a police officer’s day. Their main duties include patrolling schools, dealing with individuals with mental health difficulties, and hiding poverty from the public eye—with Montreal’s new curfew laws, this goes as far as criminalizing homelessness.

Even more duties include helping the political agenda of certain groups, and enforcing immigration policies—think of the U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement—among many other non-crime-related activities.

Vitale urges that the police should not be involved in dealing with individuals with mental disorders, as that is criminalizing mental illness. He adds that sex work should not be policed because that harms society’s most vulnerable, and ending the war on drugs is a crucial step towards ending policing and prisons.

The police are not an institution that was created to protect us. As political scientist David Bayley argued: "The police do not prevent crime. […] Yet the police pretend that they are society’s best defence against crime and continually argue that if they are given more resources, especially personnel, they will be able to protect communities against crime. This is a myth.”

ACAB simply means that, although some cops may lead what they believe to be an honest life, all cops work for an inherently oppressive institution that must be abolished in order to reinvest in transformative justice.

This article originally appeared in The Resistance Issue, published April 13, 2021.

_1_600_375_90_s_c1.jpg)

__600_375_s_c1.png)