Concordia Research on Orgasms Puts the Female Experience First

Study Shows That Your Experience is More Than the Sum of Your Parts

Orgasms are complex. But they’re also pretty simple.

Dr. Jim Pfaus, a professor of psychology at Concordia University, broke it down, explaining that “an orgasm is an orgasm is an orgasm.”

Pfaus, along with graduate students Gonzalo R. Quintana and Conall Mac Cionnaith, of Concordia’s Department in Psychology and Mayte Parada, of McGill University, recently published their research exploring the intricacies of the female orgasm in the journal Socioaffective Neuroscience and Psychology.

“That’s really the main point of the whole article,” said Pfaus. The idea is that “what people experience is valid. It’s representative of the brain and, in a way, who cares whether it’s clitoral, or vaginal, or both, or cervical, or nippular?”

The source of the pleasure, he said, “just doesn’t matter.”

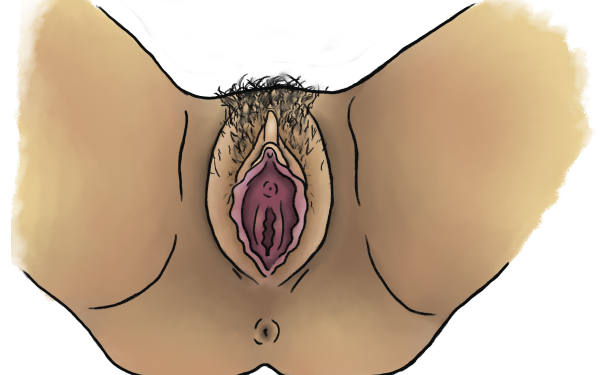

The research takes both a clinical and historical approach to understand how females experience orgasms from multiple sites—the clitoris, the vagina, the nipples or the cervix, or others—and why that fact has been disregarded in older orgasm research.

“There’s a false dichotomy out there in the perception of where orgasms come from. I mean, first, they come from the brain,” explained Pfaus. Essentially, orgasms are the brain’s interpretation of sensations. “It then falls between these two old notions,” he continued, “that the orgasm is either clitorally or vaginally.”

Pfaus explains that part of this confusion stems from early 20th century studies of sexuality. The article explains that famed psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud said there were two stages of sexual development. It was during the second, “mature genital stage” that the body developed its ability to experience pleasure from “specific zones and for specific purposes,” thereby discounting any other pleasurable sensation as “immature.”

This, Pfaus said, is the process through which Freud determined that a “pleasurable relevant thing becomes a reproductively relevant thing.”

However, Pfaus argues that this leads to an idea that orgasms must be reproductive. Non-reproductive orgasms, then, are vestigial—meaning they’re inherently functionless. And, he said, that concept stems from the male-centric perspective in which reproductive orgasms are the norm.

“Everything has been interpreted in this very man-like way, and it downplays, then, the role of what women can experience,” he said. “Women have a much greater capacity than men do, to experience [orgasms] from different sites.”

This is where the problem—in academia, in health, in research, in sex—lies.

“To put a male model on how it should be, and how it should be stimulated, what should happen and shouldn’t happen, and what you’re able to experience and unable to experience, is completely and utterly ridiculous,” Pfaus said.

In the article, he explains that male researchers Vincenzo Puppo and Stuart Brody furthered much of the vaginal versus clitoral debate. The notions they presented, Pfaus explained, seemed to be from the perspective that a female orgasm is a vestigial male orgasm—a concept which mirrors the antiquated notions that a vagina is an inverted penis or that the clitoris is a female-penis.

The article states “perhaps it is time to stop treating women’s orgasm as a sociopolitical entity with different sides telling women what they can and cannot experience or debating whether female orgasm is a vestigial male orgasm.”

This study, titled, “The whole versus the sum of some of the parts: toward resolving the apparent controversy of clitoral versus vaginal orgasms,” was led by three men, including Pfaus, and one woman.

It is worth noting as well that Pfaus signed a petition in January to reinstate Dr. Kenneth Zucker to Toronto’s Centre for Addiction and Mental Health. Zucker was dismissed due to allegations of discrediting the validity of transgender children in his practice.

“To put a male model on how it should be […] is completely and utterly ridiculous.” – Dr. Jim Pfaus

The study of female orgasms, Pfaus explained, needs to shift from exploration of a physiological reality to experiential. The fact is that one’s capacity to have an orgasm comes from their previous sexual experience and not from their biological make-up, Pfaus added.

“These zones that carry sensory information, they’re all there, everybody has them but everybody has different thresholds for these [sites],” he said.

Identical twins, for example, experience orgasms differently. He explained that in past studies, it was found that twins typically share the same sensation less than 50 per cent of the time.

“How the hell is that possible if it’s just a physiological thing? It’s got to be experiential!” exclaimed Pfaus. “Everybody is created different, even though the capacity is somewhat equivalent. Really, what you need is self-exploration.”

While he agreed that giving children sex toys might be a little too far, Pfaus explained that sexual education needs to start younger, and needs to be more all encompassing. He said that children aren’t told that it’s okay to explore their bodies themselves, to learn what feels good and what doesn’t.

Pfaus recounted multiple examples in which colleagues of his had difficulties with their Institutional Review Boards and Ethics Review Boards, resulting in yearlong waits to have their research approved or having to jump through hoops to finish their studies. The ERBs, he said, wouldn’t “let them touch this [subject] with a ten foot pole.”

One instance, he recalled, was when a grad student at McGill was forbidden from completing his study on ejaculation latency in men and so turned to Concordia’s labs instead. The difference, he joked, came down to “one place where you can’t do stuff, and another place where your colleagues are totally behind your risky research.”

Is this resistance justifiable?

“I don’t think so, but I understand why it happens,” answered A. Stephanie Bailey, who graduated with her Master’s in Psychiatry from McGill, with research focusing on human sexuality. Part of the logic behind it, she says, stems from the nature of department conducting the study. For example, she said, a medically backed study, with numbers and data, is more easily digestible by ERBs. The results are quantifiable.

“From a medical perspective, there’s a mandate to help people,” Bailey said. When it comes to studies on sexuality, the question is whether it is medically important. Bailey said it’s important to reflect on how the outcome of this research impacts a person’s life. “Is it doing more harm than good?” she asked.

She did not, however, discount the importance of these studies. “If you’re looking at histories,” she offered as a an example, “you can say a lot about where we should go.”

If you were to ask Pfaus, chances are he would say the next place we should go is inwards. After all, “a body is to be explored. It’s owned by you, it’s to be explored by you.”

1web_900_600_90.jpg)

_600_832_s.png)

_1__600_375_90_s_c1.jpg)